Home » social media (Page 4)

Category Archives: social media

Joss Whedon, Dr. Horrible, and the Future of Web Media?

I’m pleased to announce that my article Joss Whedon, Dr. Horrible, and the Future of Web Media? is finally available. Here’s the abstract:

In the 2007 Writers Guild of America strike, one of the areas in dispute was the question of residual payments for online material. On the picket line, Buffy creator Joss Whedon discussed new ways online media production could be financed. After the strike, Whedon self-funded a web media production, Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog. Whedon and his collaborators positioned Dr. Horrible as an experiment, investigating whether original online media content created outside of studio funding could be financially viable. Dr. Horrible was a bigger hit than expected, with a paid version topping the iTunes charts and a DVD release hitting the number two position on Amazon. This article explores which factors most obviously contributed to Dr. Horrible’s success, whether these factors are replicable by other media creators, the incorporation of fan labor into web media projects, and how web-specific content creation relates to more traditional forms of media production.

The official version is available in the new issue of Popular Communication (vol 11, no. 2). If you can’t access the article due to the paywall, then there’s an open access pre-print available at Academia.edu.

Digital Culture Links: April 25th

Links through to April 22nd (catching up!):

- Siri secrets stored for up to 2 years [WA Today] – “Siri isn’t just a pretty voice with the answers. It’s also been recording and keeping all the questions users ask. Exactly what the voice assistant does with the data isn’t clear, but Apple confirmed that it keeps users’ questions for up to two years. Siri, which needs to be connected to the internet to function, sends all of its users’ queries to Apple. Apple revealed the information after

Wired posted an article raising the question and highlighting the fact that the privacy statement for Siri wasn’t very clear about how long that information is kept or what would be done with it.” - Now playing: Twitter #music [Twitter Blog] – Not content to be TV’s second screen, Twitter wants to be the locus of conversations about music, too: “Today, we’re releasing Twitter #music, a new service that will change the way people find music, based on Twitter. It uses Twitter activity, including Tweets and engagement, to detect and surface the most popular tracks and emerging artists. It also brings artists’ music-related Twitter activity front and center: go to their profiles to see which music artists they follow and listen to songs by those artists. And, of course, you can tweet songs right from the app. The songs on Twitter #music currently come from three sources: iTunes, Spotify or Rdio. By default, you will hear previews from iTunes when exploring music in the app. Subscribers to Rdio and Spotify can log in to their accounts to enjoy full tracks that are available in those respective catalogs.

- Android To Reach 1 Billion This Year | Google, Eric Schmidt, Mobiles [The Age] – “Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt predicts there will be more than 1 billion Android smartphones in use by the end of the year.”

- Soda Fountains, Speeding, and Password Sharing [The Chutry Experiment] – Fascinating post about the phenomenon of Netflix and HBO Go password sharing in the US. When a NY Times journalist admitted to this (seemingly mainstream) practice, it provoked a wide-ranging discussion about the ethics and legality of many people pooling resources to buy a single account. Is this theft? Is it illegal (apparently so)? And, of course, Game of Thrones take a centre seat!

- “Welcome to the New Prohibition” [Andy Baio on Vimeo] – Insightful talk from Andy Baio about the devolution of copyright into an enforcement tool and revenue extraction device rather than protecting or further the production of artistic material in any meaningful way. For background to this video see Baio’s posts “No Copyright Intended” and “Kind of Screwed”.

- Instagram Today: 100 Million People [Instagram Blog] – Instagram crosses the 100 million (monthly) user mark.

RIOT gear: your online trail just got way more visible

By Tama Leaver, Curtin University

The recent publication of a leaked video demonstrating American security firm Raytheon’s social media mining tool RIOT (Rapid Information Overlay Technology) has rightly incensed individuals and online privacy groups.

In a nutshell, RIOT – already shared with US government and industry as part of a joint research and development effort in 2010 – uses social media traces to profile people’s activities, map their contacts, and predict their future activities.

Yet the most surprising thing isn’t how RIOT works, but that the information it mines is what we’ve each already shared publicly.

Getting to know you

In the above video, RIOT analyses social media accounts – specifically Facebook, Twitter, Gowalla and Foursquare – and profiles an individual.

In just a few seconds, RIOT manages to extract photographs as well are the times and exact location of frequently visited places. This information is then sorted and graphed, making it relatively easy to predict likely times and locations of future activity.

RIOT can also map an individual’s network of personal and professional connections. In the demonstration video, a Raytheon employee is surveyed, and the software shows who his friends are, where he’s been and, most ominously, predicts that the most likely time and place to find him is at a specific gym at 6am on a Monday morning.

Privacy concerns

The RIOT software quite rightly raises concerns about the way online information is being treated.

Since privacy rules and regulations around social media are still in their infancy, it’s hard to tell if any legal boundaries have been crossed. This is especially unclear since it appears, from the video at least, that RIOT only scrutinises information already publicly visible on the web.

The usefulness of some social media tools for mapping a person’s activity are abundantly clear. Foursquare, for example, basically produces a database of the times and places someone elects to “check-in” to specific locations.

Checking-in allows other Foursquare users to interact with that individual, but the record is basically a map of someone’s activities. Foursquare can be a great service, allowing social networking, discounts from businesses, and various location-based activities, but it also leaves a huge data trail.

Foursquare, though, has a (relatively) small user base (around 30 million) compared to Facebook (more than one billion) – although Facebook, as we know, also allows users to check-in by specifying a location in updates and posts. But the richest source of information we tend to share publicly, but not even think about, is our photographs.

Picture this

Every modern smartphone, whether an iPhone, Windows or Android device, by default saves certain information every time you take a photograph. This information about the photograph is saved using something called the Exchangeable image file format, or “exif” data.

Exif data typically includes camera settings, such as how long the camera lens was open and whether the flash fired, but on smartphones also includes the exact geographic location (latitude and longitude) and time that each photograph is taken.

Thus, all of those photographs of celebrations, birthdays, and our kids at the beach all include a digital record of where and when each and every event occurred.

Given that so many of us share photographs online using Facebook or Twitter or Instagram or Flickr, it’s not surprising that RIOT might be able to build a picture of where we’ve been and use that to guess where we might be in the future.

Yet we don’t have to leave this trail. Most smartphones have the ability to turn geographic location information off so that it’s not recorded when we take photographs.

Most of us never think to turn these options off because we don’t think about our social media persisting, but it does. Our social media fragments – our photos and posts – have no expiry date so it’s worth taking a moment when we set up a new phone or account and tweak the settings to only share what you really want to share.

If RIOT demonstrates anything, it’s the fact that information shared publicly online will likely be read, shared, copied, stored and analysed in ways we didn’t immediately think about.

If we take the time to adjust our privacy settings and sharing options, we can exercise some control over the sort of profile RIOT, or any future tool, might build about us.

Tama Leaver receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

![]()

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.

Digital Culture Links: January 29th

Links for January 29th:

- Vines Map Mashup – See where Vines are being posted in real-time on a map – And now there is a mashup, showing where Vine video snippets are being posted in realtime across the globe. Quite compelling to watch.

- 3D-print your face in chocolate for that special Valentine’s Day gift [guardian.co.uk] – While I’m a big fan of 3d printing, this seems just a little too creepy for me: “Stuck for a Valentine’s Day gift with that special personal touch? A Japanese 3D-printing company may well have the answer – providing the opportunity for you to print your own face in chocolate. Shibuya’s FabCafe is offering a two-day workshop for budding techno-chocolatiers to learn how to transform their face into a sinister edible treat. For 6,000 Yen (£40), you can have your head scanned and turned into a 3D digital model, which is then printed in plastic in high definition on a ProjetHD printer. A silicon mould is made from this positive form and filled with melted chocolate – and the final product can be secreted in a box of chocolates and presented to your unsuspecting loved one.”

- Twitter’s Vine Has A Porn Problem [TechCrunch] – Everyone is shocked to discover that since anyone can post their 6-second videos on Vine, a few people are posting porn. *OMFG*

- vinepeek – An endless stream of recent Vine video posts (hypnotic): “vinepeek shows you newly posted Vines in realtime. Sit back and watch the world in 6 second bites. Best viewed on a desktop browser. This stream is coming straight from Vine and is unmoderated. You have been warned! 🙂 Unlike lightning, sometimes Vines strike twice. Please be patient if you see a Vine more than once. If it seems to freeze, refresh the page.”

- Vine: A new way to share video [Twitter Blog] – Twitter releases Vine, a micro-video-sharing app, which lets users post videos of up to 6 seconds in length (mp4s, not GIFs).

- Facebook’s Graph Search tool causes increasing privacy concerns [Technology | guardian.co.uk] – actualfacebookgraphsearches.tumblr.com makes the news: “Privacy concerns are mounting around Facebook’s recently announced search tool, after it was used to unearth lists of people related to supporters of the outlawed Chinese group Falun Gong and companies apparently employing self-declared racists. Graph Search, Facebook’s answer to Google’s search engine, was launched last week by founder Mark Zuckerberg, who promised it would help people find friends who share their interests. Critics argued it could be also be used to unearth compromising information on Facebook’s 1 billion members. In a blog launched on Wednesday, a series of controversial search results have been made public, showing the extent to which those who share photos, personal information and “likes” on Facebook could have their privacy invaded.”

- How to Protect Your Privacy from Facebook’s Graph Search [Electronic Frontier Foundation] – “Earlier this week, Facebook launched a new feature—Graph Search—that raised some privacy concerns with us. Graph Search allows users to make structured searches to filter through friends, friends of friends, and strangers. This feature relies on your profile information being made widely or publicly available, yet there are some Likes, photos, or other pieces of information that you might not want out there. Since Facebook removed the ability to remove yourself from search results altogether, we’ve put together a quick how-to guide to help you take control over what is featured on your Facebook profile and on Graph Search results.”

Facebook’s Graph Search, privacy and the social media contradiction

[Last week I wrote the article below for The Conversation. It’s reproduced here mainly for my records …]

Initial responses to Facebook’s newly announced Graph Search (a name only a software engineer could love) appear to be split into two main camps:

- those who have celebrated the level of nuanced detail that can be retrieved by the tool

- those who suggest Graph Search represents further erosion of privacy on the social networking giant.

Both responses are entirely valid.

So, what is Graph Search?

If Graph Search works as advertised, then it’s a technical marvel, allowing a huge array of complex searches using real questions, not just keywords.

Type in “Which females in my area, around my age, support the Fremantle Dockers and are single?” and suddenly Facebook becomes a very specific and useful dating service. But this nuanced, “natural language” searching also means that, for many users, it will be even easier to delve into the minute details that are seemingly hidden on your connections’ Timelines.

The discussion around the release of Graph Search highlights something more important – something that could be described as the “social media contradiction”.

‘Social’ media?

“Social” implies conversation and other communication which we are accustomed to thinking of as ephemeral – largely disappearing after the interaction is finished. Conversations in the street or telephone calls generally don’t persist once they’re done.

To Facebook and other social media service providers, it’s the media side of social media that matters. Media fills the databases – the most valuable part of Facebook to marketers (the actual customers of Facebook) – and this media has no expiration date.

Once entered, my relationship status, likes, photos, comments on friends’ photos, silly news stories I share and current location are all media elements which are in the Facebook database in perpetuity … unless I go to some pains to remove them.

Social media networks generally aren’t run by governments, and rarely by philanthropists. Most are for-profit corporations. Facebook, Google, LinkedIn and most other online services have shareholders and are out to make a profit.

Different, but increasingly similar

Every time someone has a conversation on Facebook, or does a search on Google, that information gets stored in a database. Google and Facebook make their money by harnessing that enormous database and allowing advertisers to reach people making specific searches or discussing specific topics.

Graph Search makes the experience of Facebook more like the experience of Google. An effusive profile of the Graph Search team in Wired notes that the core software engineers have both defected from Google, including Lars Rasmussen who was one of the original creators of Google Maps (and the ill-fated Google Wave).

Notably, while Facebook is becoming more searchable, Google has been trying to gather more social information about its users by merging the privacy policies governing all of its products into one, and linking them all to the company’s social network, Google Plus.

These two online giants might have different origins, but they are looking increasingly alike.

‘Privacy aware’?

Be it Google or Facebook, privacy is a key issue in social media, and one which is at the heart of the social media contradiction. At any given moment, the design of a service like Facebook may make some information feel private, even when it’s technically not.

When Facebook shifted from profiles to Timelines, old conversations that were buried in the past were suddenly easy to find by scrolling back through the years. Graph Search takes that a step further, as anything in your history – any past conversations, any old photos or anything else shared on Facebook – will be searchable by others if your privacy settings allow it.

Limiting the visibility of a photo to “friends of friends” doesn’t just control who will see it initially on their newsfeed. It now controls who is able to search for that photo, in terms of location, caption, people tagged in it, or whatever other data exists about that photograph.

Facebook touts Graph Search as “privacy aware” but all that really means is the service will respect Facebook’s already complicated privacy options.

Be aware, act sensibly

As Facebook makes our data accessible in yet another unexpected way, it’s perhaps time to stop reacting to each change with outrage, and become aware of the ongoing social media contradiction.

Every online conversation we have, every photo we upload, every item we share goes into a database. Corporations will try to harness that database to make money. That doesn’t make Google or Facebook malicious, it just makes them a business.

The social media contradiction occurs when we imagine Facebook or Google to be a service, not a business. If we keep in mind anything shared will be stored forever, analysed, and harnessed to make money, then, like Facebook, we’ll be aware that social media is media, not just social.

As users, our business is to try and be aware of the privacy settings available on these services and take our options seriously. Facebook might change how their database is accessed and utilised, but if we’ve only shared something with our Facebook friends, they’re the only ones who can search for it.

Of course, if it’s not on Facebook at all, no-one can use Facebook to find it.

[This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article. ]

Digital Culture Links: January 16th

Links through to January 16th:

- Beatles’ First Single Enters Public Domain — In Europe [Techdirt] – The Beatles remain the iconic pop group, so news on VVN/Music that their very first single has now entered the public domain is something of a landmark moment in music:

The Beatles first single, Love Me Do / P.S. I Love You, has entered the public domain in Europe and small labels are already taking advantage of the situation.The European copyright laws grant ownership of a recorded track for fifty years, which Love Me Do just passed. That means that, starting January 1 of 2013, anyone who wants to put out the track is free to do so.

Unfortunately, if you’re in the US, you’ll probably have to wait until 2049 or so. And things are about to get worse in Europe too. As Techdirt reported, back in 2011 the European Union agreed to increase the copyright term for sound recordings by 20 years, - App Store Tops 40 Billion Downloads with Almost Half in 2012 [Apple – Press Info] – Apple passes 40 billion app downloads: “Apple® today announced that customers have downloaded over 40 billion apps*, with nearly 20 billion in 2012 alone. The App Store℠ has over 500 million active accounts and had a record-breaking December with over two billion downloads during the month. Apple’s incredible developer community has created over 775,000 apps for iPhone®, iPad® and iPod touch® users worldwide, and developers have been paid over seven billion dollars by Apple.”

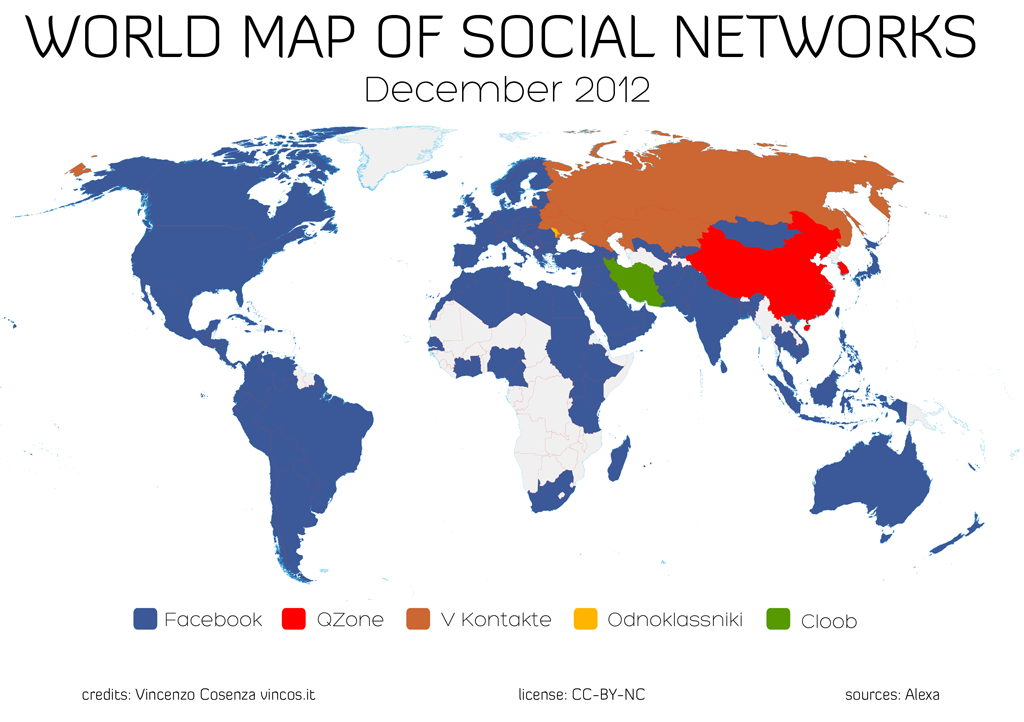

- World Map of Social Networks [Vincos Blog] –

“December 2012, a new edition of my World Map of Social Networks, showing the most popular social networking sites by country, according to Alexa traffic data (Google Trends for Websites was shut down on September 2012). Facebook with 1 billion active users has established its leadership position in 127 out of 137 countries analyzed. One of the drivers of its growth is Asia that with 278 million users, surpassed Europe, 251 million, as the largest continent on Facebook. North America has 243 million users, South America 142 million. Africa, almost 52 million, and Oceania just 15 million (source: Facebook Ads Platform). In the latest months Zuckerberg’s Army conquered Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia and Vietnam.”

“December 2012, a new edition of my World Map of Social Networks, showing the most popular social networking sites by country, according to Alexa traffic data (Google Trends for Websites was shut down on September 2012). Facebook with 1 billion active users has established its leadership position in 127 out of 137 countries analyzed. One of the drivers of its growth is Asia that with 278 million users, surpassed Europe, 251 million, as the largest continent on Facebook. North America has 243 million users, South America 142 million. Africa, almost 52 million, and Oceania just 15 million (source: Facebook Ads Platform). In the latest months Zuckerberg’s Army conquered Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia and Vietnam.” - Over 8 million game downloads on Christmas Day! [Rovio Entertainment Ltd] – Rovio’s big Christmas download haul: “Wow, what a year! We released four critically-acclaimed bestselling mobile games, developed two top-rated Facebook games, and reached more than a billion downloads — all before our 3rd “Birdday”! Angry Birds Star Wars and Bad Piggies in particular have dominated the app charts, with Angry Birds Star Wars holding the #1 position on the US iPhone chart ever since its release! To top it all off, we had 30 million downloads during Christmas week (December 22-29) and, on Christmas Day, over 8 million downloads in 24 hours alone!”

- R18+ game rating comes into effect [ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)] – Finally: “An R18+ video game rating has come into effect across Australia after a deal between the states and the Commonwealth last year. The change means some games that were previously unavailable to adults can go on sale, whereas others that could be accessed by children will become restricted. The issue had divided interest groups, with some claiming the new classification would protect children but others feared it would expose them to more violent games. Legislation to approve the rating was passed by the Senate in June. Under the previous classification regime, the highest rating for computer games was MA15+, meaning overseas adults-only games were either banned in Australia or given a lower classification, allowing children to obtain them.”

- Two billion YouTube music video views disappear … or just migrate? [Technology | guardian.co.uk] – Despite rumours of massive cuts to major record labels’ YouTube channel counts, the explanation is rather more banal: “Universal and Sony have, since 2009, been moving their music videos away from their YouTube channels and over to Vevo, the music industry site the two companies own with some investors from Abu Dhabi. YouTube, meanwhile, thinks that is only right to count channel video views for videos that are still actually present on the channels – which means that whenever YouTube got round to reviewing the music majors’ channels on its site, a massive cut was always going to be in order.”

Digital Culture Links: Last Links for 2012.

Happy New Year, originally uploaded by Tama Leaver.

End of year links:

- Best Memes of 2012: Editorial Choices [Know Your Meme] – The best memes of 2012, according to Know Your Meme:

#10: Sh*t People Say

#9: What People Think I Do

#8: Overly Attached Girlfriend

#7: Ehrmagerd

#6: Ridiculously Photogenic Guy

#5: Somebody That I Used to Know

#4: Kony 2012

#3: Call Me Maybe

#2: Grumpy Cat

#1: Gangnam Style

Personally, I’d add Texts from Hillary, McKayla is Not Impressed and Binders Full of Women to the list! - Posterous Spaces backup tool available now [The Official Posterous Space] – Posterous adds the ability for users to download their entire Posterous sites as a zip file, complete with images and a usable (if dull) html interface. There hasn’t been a lot of movement with Posterous since the team were bought out by Twitter, so this new tool may signal the beginning of the end of the end for Posterous, which is a real shame since it’s still a more robust tool than Tumblr in a number of ways.

- App sales soar in 2012 [Technology | The Guardian] – “Shiny new tablets and smartphones given as presents make Christmas Day and Boxing Day the two most lucrative days of the year for app sales. Yet in the apps economy, turkeys are a year-round phenomenon. Thousands of new apps are released every week for devices running Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android, but most sink without trace. With an estimated 1bn apps released so far on those two platforms alone, there are relatively few winners and many losers. This month, industry analyst Canalys claimed that in the first 20 days of November, Apple’s US App Store generated $120m (£75m) of app revenues, with just 25 publishers accounting for half of that. And 24 of those 25 companies make games, including the likes of Zynga, Electronic Arts and Angry Birds publisher Rovio. But analysts suggested in August that two-thirds of Apple store apps had never been downloaded – a lifeless long tail of more than 400,000 unwanted apps.”

- 2012’s Most Popular Locations on Instagram [Instagram Blog] – “What was the most-Instagrammed place in the world this past year? The answer may surprise you. Out of anywhere else in the world, Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport tops the list. Over 100,000 photos were taken there last year! What other locations were popular in 2012? From Asia to Europe to North America, Instagrammers shared their view of the world. Read on for the full list:

* Suvarnabhumi Airport (BKK) ท่าอากาศยานสุวรรณภูมิ in Bangkok, Thailand

* Siam Paragon (สยามพารากอน) shopping mall in Bangkok, Thailand

* Disneyland Park in Anaheim, California

* Times Square in New York City

* AT&T; Park in San Francisco

* Los Angeles International Airport (LAX)

* Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles

* Eiffel Tower in Paris

* Staples Center in Los Angeles

* Santa Monica Pier in Los Angeles” - Wikipedia’s most searched articles of the year revealed [BBC News] – “A study of 2012’s most read Wikipedia articles reveals striking differences in what proved popular across the different language versions of the online encyclopaedia. Facebook topped the English edition while an entry for adult video actresses did best in Japan. Hua Shan – a Chinese mountain featuring “the world’s deadliest hiking trail” – topped the Dutch list. By contrast, cul-de-sacs were the German site’s most clicked entry. … Lower entries on the lists also proved revealing. While articles about Iran, its capital city Tehran and the country’s New Year celebrations topped the Persian list, entries about sex, female circumcision and homosexuality also made its top 10. …

English language most viewed

1. Facebook

2. Wiki

3. Deaths in 2012

4. One Direction

5. The Avengers

6. Fifty Shades of Grey

7. 2012 phenomenon

8. The Dark Knight Rises

9. Google

10. The Hunger Games” - Bug reveals ‘erased’ Snapchat videos [BBC News] – Using a simple file browser tool, users are able to find and save files sent via Snapchat, an app that’s meant to share and then erase photos, messages and video. Not surprisingly really, since all communication online is, essentially, copying files of some sort or another.

- Web tools whitewash students online [The Australian] – Universities offering web presence washing at graduation. Perhaps teaching grads to manage their own would be better.

“Samantha Grossman wasn’t always thrilled with the impression that emerged when people Googled her name. “It wasn’t anything too horrible,” she said. “I just have a common name. There would be pictures, college partying pictures, that weren’t of me, things I wouldn’t want associated with me.” So before she graduated from Syracuse University last spring, the school provided her with a tool that allowed her to put her best web foot forward. Now when people Google her, they go straight to a positive image – professional photo, cum laude degree and credentials – that she credits with helping her land a digital advertising job in New York. “I wanted to make sure people would find the actual me and not these other people,” she said. Syracuse, Rochester and Johns Hopkins in Baltimore are among the universities that offer such online tools to their students free of charge …” - Mark Zuckerberg’s sister learns life lesson after Facebook photo flap [Technology | The Guardian] – A photo from Randi Zuckerberg’s Facebook page gets taken out of context and reposted on Twitter and she complains, then goes overtly moral, tweeting: “Digital etiquette: always ask permission before posting a friend’s photo publicly. It’s not about privacy settings, it’s about human decency”The Guardian’s take: “But what’s most odious about the episode is the high-handedness of Zuckerberg’s response. Facebook makes money when users surrender their privacy. The company has made it the user’s job to defend personal information, which otherwise might be made public by default. Got a problem with that? The company’s answer always has been that users should read the privacy settings, closely, no matter how often they change. … Eva Galperin said that while Facebook has made amendments to their privacy settings, they still remain confusing to a large number of people. “Even Randi Zuckerberg can get it wrong,” she said. “That’s an illustration of how confusing they can be.”

- Twitter and Facebook get on the school timetable in anti-libel lessons [Media | The Guardian] – Some private schools in the UK are now embedding social media literacies into their curriculum, especially how to avoid defamation of others, and, I guess, how not to get sued. While it’d be nice to hear about more well-rounded literacies – like managing your identity online in its early forms – this is nevertheless a step in the right direction. I fear, though, a new digital divide might appear if social media literacies are embedded for some, not all.

- Top Tweets of 2012: Golden Tweets – Twitter’s official list of top 2012 tweets, led by Barack Obama’s “Four more years” and in second place … Justin Bieber.

- Facebook’s Poke App Is a Head-Scratcher [NYTimes.com] – Ephemeral Mobile Media: “.. it’s hard to grasp what the point of the Facebook Poke app really is. Poke, which came out last week, is a clone of Snapchat, an app popular among teenagers. Many have labeled Snapchat a “sexting” app — a messaging platform ideally suited for people who want to send short-lived photos and videos of you-know-what to get each other feeling lusty. The files self-destruct in a few seconds, ideally relieving you of any shame or consequence, unless, of course, the recipient snaps a screen shot. (Poke and Snapchat alert you if a screen shot has been taken.) It’s a bit of a head-scratcher for adults, like me and my Facebook friends, who aren’t inclined to sext with one another. We’re more used to uploading photos of pets, food, babies and concerts, which aren’t nearly as provocative. The most interesting aspect of Poke is that you can send photos and videos only of what you’re doing at that moment; you cannot send people a nice photo saved in your library …”

- Game of Thrones tops TV show internet piracy chart [BBC News] – Game of Thrones has emerged as the most-pirated TV show over the internet this year, according to news site Torrentfreak’s latest annual survey. It said one episode of the series had racked up 4,280,000 illegal global downloads – slightly more than than its estimated US television audience. … Despite all the closures, one episode of of Game of Thrones racked up 4,280,000 illegal global downloads, according to Torrentfreak. That was slightly more than than its estimated US television audience. The level of piracy may be linked to the fact that the TV company behind it – HBO – does not allow Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime or other US streaming services access to its programmes. It instead restricts them to its own HBO Go online product, which is only available to its cable subscribers. Outside the US, Torrentfreak noted that Australia was responsible for a disproportionate amount of illegal copies of Game of Thrones…”

Instagram’s Terms of Use Updated … Badly.

Despite Mark Zuckerberg implying that Facebook’s purchase wouldn’t alter the core fabric of Instagram, a billion dollar purchase price (okay, less than that after Facebook’s share price tanked) means an expectation of a significant return. Sadly, today, Instagram announced a significant update to their Terms of Use which show the decidedly Facebooksih direction that the photo-sharing service is taking to try and bring in the cash. The changes were framed by a blog post which suggests nothing major is changing, but that’s just not true. Here’s a key passage from the updated Terms of Use (which are legally binding as of 16 January 2013):

Despite Mark Zuckerberg implying that Facebook’s purchase wouldn’t alter the core fabric of Instagram, a billion dollar purchase price (okay, less than that after Facebook’s share price tanked) means an expectation of a significant return. Sadly, today, Instagram announced a significant update to their Terms of Use which show the decidedly Facebooksih direction that the photo-sharing service is taking to try and bring in the cash. The changes were framed by a blog post which suggests nothing major is changing, but that’s just not true. Here’s a key passage from the updated Terms of Use (which are legally binding as of 16 January 2013):

2. Some or all of the Service may be supported by advertising revenue. To help us deliver interesting paid or sponsored content or promotions, you agree that a business or other entity may pay us to display your username, likeness, photos (along with any associated metadata), and/or actions you take, in connection with paid or sponsored content or promotions, without any compensation to you. If you are under the age of eighteen (18), or under any other applicable age of majority, you represent that at least one of your parents or legal guardians has also agreed to this provision (and the use of your name, likeness, username, and/or photos (along with any associated metadata)) on your behalf.

3. You acknowledge that we may not always identify paid services, sponsored content, or commercial communications as such.

Or, if I could translate slightly: Instagram may, at their discretion and without telling you, use your photo to sell or promote something to other Instagram users – most likely your followers – and not even clearly identify this as an advertisement or promotion. While, strictly speaking, these Terms don’t alter the copyright status of your photos on Instagram (you own them, but give Instagram explicit permission to use them, re-use them, or let third parties use them as long as you’re still an Instagram user) the tone and spirit behind those uses have changed substantially. Sure, this might be a trade-off that many people are happy with: they get to keep using Instagram for free, and all sorts of new advertisements and promotions appear, some using images you’ve posted.

However, I fear that most people will ignore these Terms of Use changes and notifications. Ignore them, that is, until an advertisement pops up with their head or photo in it and then everyone will get loud, and angry, but unless you’re prepared to delete your Instagram account, there new Terms are absolutely binding. In the mean time, keep in mind you can always export and download all of your Instagram photos and maybe set up with a different service. For more details about what the changes mean, I recommend reading these overviews at the NY Times Bits Blog and the Social Times.

These updated changes may not worry you in the slightest, but please take the time to consider what they mean before they come into effect.

Update (21 December 2012): After considerable public backlash against the new Terms, Instagram have, for now, chosen to largely revert to their previous terms. This is a short-term win insomuch as Instagram are now aware that there are lines that their users don’t want to see crossed. Even though there was considerable misinterpretation (as far as I can see, Instagram never intended, for example, to wholesale sell anyone’s photos), concerns raised were legitimate. However, the longer term problem remains: few people ever read Terms of Use, so a change like this is only ever interpreted as a knee-jerk response against the most sensational media reports. Perhaps the salient lesson here is that at least a passing familiarity with all Terms we’ve signed up for makes us more aware of where we really stand as users, consumers and participants in a mobile media culture?

Incidentally, I’d love it if Instagram added native support for Creative Commons licenses, but I understand that as a Facebook-owned company, that’s highly unlikely. The lesson Instagram might learn from a conversation with Creative Commons, though, is having layered Terms where human-readable terms means read by all humans, not just those with law degrees.