Home » social media (Page 3)

Category Archives: social media

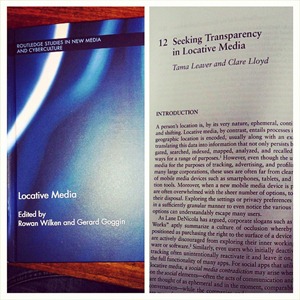

New chapter: Seeking Transparency in Locative Media

The newly-released edited collection Locative Media by Rowan Wilken and Gerard Goggin features a chapter from Clare Lloyd and me looking at issues of privacy and transparency relating to the data generated, stored and analysed when using mobile and locative-based services. Here’s the abstract:

The newly-released edited collection Locative Media by Rowan Wilken and Gerard Goggin features a chapter from Clare Lloyd and me looking at issues of privacy and transparency relating to the data generated, stored and analysed when using mobile and locative-based services. Here’s the abstract:

A person’s location is, by its very nature, ephemeral, continually changing and shifting. Locative media, by contrast, is created when a device encodes a users’ geographic location, and usually the exact time as well, translating this data into information that not only persists, but can be aggregated, searched, indexed, mapped, analysed and recalled in a variety of ways for a range of purposes However, while the utility of locative media for the purposes of tracking, advertising and profiling is obvious to many large corporations, these uses are far from transparent for many users of mobile media devices such as smartphones, tablets and satellite navigation tools. Moreover, when a new mobile media device is purchased, users are often overwhelmed with the sheer number of options, tools and apps at their disposal. Often, exploring the settings or privacy preferences of a new device in a sufficiently granular manner to even notice the various location-related options simply escapes many new users. Similarly, even those who deactivate geolocation tracking initially often unintentionally reactivate it, and leave it on, in order to use the full functionality of many apps. A significant challenge has thus arisen: how can users be made aware of the potential existence and persistence of their own locative media? This chapter examines a number of tools and approaches which are designed to inform everyday users of the uses, and potential abuses, or locative media; PleaseRobMe, I Can Stalk U, iPhone Tracker and the aptly named Creepy. These awareness-raising tools make visible the operation of certain elements of locative media, such as revealing the existence of geographic coordinates in cameraphone photographs, and making explicit possible misuses of a visible locative media trail. All four are designed as pedagogical tools, aiming to make users aware of the tools they are already using. In an era where locative media devices are easy to use but their ease occludes extremely complex data generation and potential tracking, this chapter argues that these tools are part of a significant step forward in developing public awareness of locative media, and related privacy issues.

A version of the chapter is available at Academia.edu (and just for fun, the book has a 2015 publication date, so at the moment, it’s *from the future*!)

Mapping the Ends of Identity on Instagram

At last week’s Australian and New Zealand Communication Association (ANZCA) conference at Swinburne University in Melbourne I gave a new paper by myself and Tim Highfield entitled ‘Mapping the Ends of Identity on Instagram’. The slides, abstract, and audio recording of the talk are below:

While many studies explore the way that individuals represent themselves online, a less studied but equally important question is the way that individuals who cannot represent themselves are portrayed. This paper outlines an investigation into some of those individuals, exploring the ends of identity – birth and death – and the way the very young and deceased are portrayed via the popular mobile photo sharing app and platform Instagram. In order to explore visual representations of birth and death on Instagram, photos with four specific tags were tracked: #birth, #ultrasound, #funeral and #RIP. The data gathered included quantitative and qualitative material. On the quantitative front, metadata was aggregated about each photo posted for three months using the four target tags. This includes metadata such as the date taken, place taken, number of likes, number of comments, what tags were used, and what descriptions were given to the photographs. The quantitative data gives also gives an overall picture of the frequency and volume of the tags used. To give a more detailed understanding of the photos themselves, on one day of each month tracked, all of the photographs on Instagram using the four tags were downloaded and coded, giving a much clearer representative sampling of exactly how each tag is used, the sort of photos shared, and allowed a level of filtering. For example, the #ultrasound hashtag includes a range of images, not just prenatal ultrasounds, including both current images (taken and shared at that moment), historical images, collages, and even ultrasound humour (for example, prenatal ultrasound images with including a photoshopped inclusion of a cash, or a cigarette, joking about the what the future might hold). This paper will outline the methods developed for tracking Instagram photos via tags, it will then present a quantitative overview of the uses and frequency of the four hashtags tracked, give a qualitative overview of the #ultrasound and #RIP tags, and conclude with some general extrapolations about the way that birth and death are visually represented online in the era of mobile media.

And the audio recording of the talk is available on Soundcloud for those who are willing to brave the mediocre quality and variable volume (because I can’t talk without pacing about, it seems!).

Facebook in Education: Special Issue of Digital Culture & Education

I’m pleased to announced that the special themed issue of Digital Culture and Education on Facebook in Education, edited by Mike Kent and I, has been released. The issue features an introductory article by Mike and I, ‘Facebook in Education: Lessons Learnt’ in which we may have some opinions about whether the hype around MOOCs and disruptive online education ignores the very long history of learning online (hint: it does). As something of a corrective to that hype, this issue explores different aspects of the complicated relationship between Facebook as a platform and learning and teaching in higher education.

This issue features ‘“Face to face” Learning from others in Facebook Groups‘ by Eleanor Sandry, ‘Exploiting fluencies: Educational expropriation of social networking site consumer training‘ by Lucinda Rush and D.E. Wittkower, ‘Learning or Liking: Educational architecture and the efficacy of attention‘ by Leanne McRae, and ‘Separating Work and Play: Privacy, Anonymity and the Politics of Interactive Pedagogy in Deploying Facebook in Learning and Teaching’ by Rob Cover.

Also, watch this space in about a month for the related and slightly larger related work in the same area.

Is Facebook finally taking anonymity seriously?

By Tama Leaver, Curtin University and Emily van der Nagel, Swinburne University of Technology

Having some form of anonymity online offers many people a kind of freedom. Whether it’s used for exposing corruption or just experimenting socially online it provides a way for the content (but not its author) to be seen.

But this freedom can also easily be abused by those who use anonymity to troll, abuse or harass others, which is why Facebook has previously been opposed to “anonymity on the internet”.

So in announcing that it will allow users to log in to apps anonymously, is Facebook is taking anonymity seriously?

Real identities on Facebook

CEO Mark Zuckerberg has been committed to Facebook as a site for users to have a single real identity since its beginning a decade ago as a platform to connect college students. Today, Facebook’s core business is still about connecting people with those they already know.

But there have been concerns about what personal information is revealed when people use any third-party apps on Facebook.

So this latest announcement aims to address any reluctance some users may have to sign in to third-party apps. Users will soon be able to log in to them without revealing any of their wealth of personal information.

That does not mean they will be anonymous to Facebook – the social media site will still track user activity.

It might seem like the beginning of a shift away from singular, fixed identities, but tweaking privacy settings hardly indicates that Facebook is embracing anonymity. It’s a long way from changing how third-party apps are approached to changing Facebook’s entire real-name culture.

Facebook still insists that “users provide their real names and information”, which it describes as an ongoing “commitment” users make to the platform.

Changing the Facebook experience?

Having the option to log in to third-party apps anonymously does not necessarily mean Facebook users will actually use it. Effective use of Facebook’s privacy settings depends on user knowledge and motivation, and not all users opt in.

A recent Pew Research Center report reveals that the most common strategy people use to be less visible online is to clear their cookies and browser history.

Only 14% of those interviewed said they had used a service to browse the internet anonymously. So, for most Facebook users, their experience won’t change.

Facebook login on other apps and websites

Facebook offers users the ability to use their authenticated Facebook identity to log in to third-party web services and mobile apps. At its simplest and most appealing level, this alleviates the need for users to fill in all their details when signing up for a new app. Instead they can just click the “Log in with Facebook” button.

For online corporations whose businesses depend on building detailed user profiles to attract advertisers, authentication is a real boon. It means they know exactly what apps people are using and when they log in to them.

Automated data flows can often push information back into the authenticating service (such as the music someone is playing on Spotify turning up in their Facebook newsfeed).

While having one account to log in to a range of apps and services is certainly handy, this convenience means it’s almost impossible to tell what information is being shared.

Is Facebook just sharing your email address and full name, or is it providing your date of birth, most recent location, hometown, a full list of friends and so forth? Understandably, this again raises privacy concerns for many people.

How anonymous login works

To address these concerns, Facebook is testing anonymous login as well as a more granular approach to authentication. (It’s worth noting, neither of these changes have been made available to users yet.)

Given the long history of privacy missteps by Facebook, the new login appears to be a step forward. Users will be told what information an app is requesting, and have the option of selectively deciding which of those items Facebook should actually provide.

Facebook will also ask users whether they want to allow the app to post information to Facebook on their behalf. Significantly, this now places the onus on users to manage the way Facebook shares their information on their behalf.

In describing anonymous login, Facebook explains that:

Sometimes people want to try out apps, but they’re not ready to share any information about themselves.

It’s certainly useful to try out apps without having to fill in and establish a full profile, but very few apps can actually operate without some sort of persistent user identity.

The implication is once a user has tested an app, to use its full functionality they’ll have to set up a profile, probably by allowing Facebook to share some of their data with the app or service.

Taking on the competition

The value of identity and anonymity are both central to the current social media war to gain user attention and loyalty.

Facebook’s anonymous login might cynically be seen as an attempt to court users who have flocked to Snapchat, an app which has anonymity built into its design from the outset.

Snapchat’s creators famously turned down a US$3 billion buyout bid from Facebook. Last week it also revealed part of its competitive plan, an updated version of Snapchat that offers seamless real-time video and text chat.

By default, these conversations disappear as soon as they’ve happened, but users can select important items to hold on to.

Whether competing with Snapchat, or any number of other social media services, Facebook will have to continue to consider the way identity and anonymity are valued by users. At the moment its flirting with anonymity is tokenistic at best.

![]()

Tama Leaver receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC).

Emily van der Nagel does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

A Methodology for Mapping Instagram Hashtags

At this week’s Digital Humanities Australasia 2014 conference in Perth, Tim Highfield and I presented the first paper from a new project looking a visual social media, with a particular focus on Instagram. The slides and abstract are below (sadly with Slideshare discontinuing screencasts, I’m not sure if I’ll be adding audio to presentations again):

Social media platforms for content-sharing, information diffusion, and publishing thoughts and opinions have been the subject of a wide range of studies examining the formation of different publics, politics and media to health and crisis communication. For various reasons, some platforms are more widely-represented in research to date than others, particularly when examining large-scale activity captured through automated processes, or datasets reflecting the wider trend towards ‘big data’. Facebook, for instance, as a closed platform with different privacy settings available for its users, has not been subject to the same extensive quantitative and mixed-methods studies as other social media, such as Twitter. Indeed, Twitter serves as a leading example for the creation of methods for studying social media activity across myriad contexts: the strict character limit for tweets and the common functions of hashtags, replies, and retweets, as well as the more public nature of posting on Twitter, mean that the same processes can be used to track and analyse data collected through the Twitter API, despite covering very different subjects, languages, and contexts (see, for instance, Bruns, Burgess, Crawford, & Shaw, 2012; Moe & Larsson, 2013; Papacharissi & de Fatima Oliveira, 2012)

Building on the research carried out into Twitter, this paper outlines the development of a project which uses similar methods to study uses and activity on through the image-sharing platform Instagram. While the content of the two social media platforms is dissimilar – short textual comments versus images and video – there are significant architectural parallels which encourage the extension of analytical methods from one platform to another. The importance of tagging on Instagram, for instance, has conceptual and practical links to the hashtags employed on Twitter (and other social media platforms), with tags serving as markers for the main subjects, ideas, events, locations, or emotions featured in tweets and images alike. The Instagram API allows queries around user-specified tags, providing extensive information about relevant images and videos, similar to the results provided by the Twitter API for searches around particular hashtags or keywords. For Instagram, though, the information provided is more detailed than with Twitter, allowing the analysis of collected data to incorporate several different dimensions; for example, the information about the tagged images returned through the Instagram API will allow us to examine patterns of use around publishing activity (time of day, day of the week), types of content (image or video), filters used, and locations specified around these particular terms. More complex data also leads to more complex issues; for example, as Instagram photos can accrue comments over a long period, just capturing metadata for an image when it is first available may lack the full context information and scheduled revisiting of images may be necessary to capture the conversation and impact of an Instagram photo in terms of comments, likes and so forth.

This is an exploratory study, developing and introducing methods to track and analyse Instagram data; it builds upon the methods, tools, and scripts used by Bruns and Burgess (2010, 2011) in their large-scale analysis of Twitter datasets. These processes allow for the filtering of the collected data based on time and keywords, and for additional analytics around time intervals and overall user contributions. Such tools allow us to identify quantitative patterns within the captured, large-scale datasets, which are then supported by qualitative examinations of filtered datasets.

References

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2010). Mapping Online Publics. Retrieved from http://mappingonlinepublics.net

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2011, June 22). Gawk scripts for Twitter processing. Mapping Online Publics. Retrieved from http://mappingonlinepublics.net/resources/

Bruns, A., Burgess, J., Crawford, K., & Shaw, F. (2012). #qldfloods and @ QPSMedia: Crisis Communication on Twitter in the 2011 South East Queensland Floods. Brisbane. Retrieved from http://cci.edu.au/floodsreport.pdf

Moe, H., & Larsson, A. O. (2013). Untangling a Complex Media System. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 775–794. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2013.783607

Papacharissi, Z., & de Fatima Oliveira, M. (2012). Affective News and Networked Publics: The Rhythms of News Storytelling on #Egypt. Journal of Communication, 62, 266–282. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01630.x

Captured at Birth? Intimate Surveillance and Digital Legacies

At the end of January 2014 I was delighted to participate in the Surveillance, Copyright, Privacy: The end of the open internet conference held at the University of Otago in New Zealand. It was an inspiring three days looking critically at the way privacy and surveillance are increasingly at war in contemporary culture, which the eternal bugbear of copyright continues to look large. For a sense of the conference, Rosie Overell has collated the tweets from the event in four Storify collections: day one; morning of day 2; afternoon of day 2; and day 3.

The paper I presented was entitled ‘Captured at Birth? Intimate Surveillance and Digital Legacies’. Here’s the slides and abstract:

From social media to CCTV cameras, surveillance practices have been largely normalised in contemporary cultures. While sousveillance – surveillance and self-surveillance by everyday individuals – is often situated as a viable means of subverting and making visible surveillance practices, this is premised on those being surveyed having sufficient agency to actively participate in escaping or re-directing an undesired gaze (Albrechtslund, 2008; Fernback, 2013; Mann, Nolan, & Wellman, 2002). This paper, however, considers the challenges that come with what might be termed intimate surveillance: the processes of recording, storing, manipulating and sharing information, images, video and other material gathered by loved ones, family members and close friends. Rather than considering the complex negotiations often needed between consenting adults in terms of what material can, and should, be shared about each other, this paper focuses on the unintended digital legacies created about young people, often without their consent. As Deborah Upton (2013, p. 42) has argued, for example, posting first ultrasound photographs on social media has become a ritualised and everyday part of process of visualising and sharing the unborn. For many young people, their – often publicly shared – digital legacy begins before birth. Along a similar line, a child’s early years can often be captured and shared in a variety of ways, across a range of platforms, in text, images and video. The argument put forward is not that such practices are intrinsically wrong, or wrong at all. Rather, the core issue is that so many of the discussions about privacy and surveillance put forward in recent years presume that those under surveillance have sufficient agency to at least try and do something about it. When parents and others intimately survey their children and share that material – almost always with the very best intentions – they often do so without any explicit consideration of the privacy, rights or (likely unintended) digital legacy such practices create. A legacy which young people will have to, at some point, wrestle with, especially in a digital landscape increasingly driven by ‘real names’ policies (Zoonen, 2013). Inverting the overused media moral panic about young people’s sharing practices on social media, this paper argues that young people should be more concerned about the quite possibly inescapable legacy their parents’ documenting and sharing practices will create. Ensuring that intimate surveillance is an informed practice, better educational resources and social media literacy practices are needed for new parents and others responsible for managing the digital legacies of others.

References

Albrechtslund, A. (2008). Online Social Networking as Participatory Surveillance. First Monday, 13(3). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2142/1949

Fernback, J. (2013). Sousveillance: Communities of resistance to the surveillance environment. Telematics and Informatics, 30(1), 11–21. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2012.03.003

Lupton, D. (2013). The Social Worlds of the Unborn. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Mann, S., Nolan, J., & Wellman, B. (2002). Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments. Surveillance & Society, 1(3), 331–355.

Zoonen, L. van. (2013). From identity to identification: fixating the fragmented self. Media, Culture & Society, 35(1), 44–51. doi:10.1177/0163443712464557

For me the trip to Dunedin had the added bonus of spending some time visiting family and reacquainting myself after far too long away with the beautiful city I was born in.

Birth, Death and Facebook

Last week, as the inaugural paper in CCAT’s new seminar series Adventures in Culture in Technology (ACAT), I presented a more in depth, although still in progress, talk based on a paper I’m finishing on Facebook and the questions of birth and death. Here’s the slides along with recorded audio if you’re interested:

The talk abstract: While social media services including the behemoth Facebook with over a billion users, promote and encourage the ongoing creation, maintenance and performance of an active online self, complete with agency, every act of communication is also recorded. Indeed, the recordings made by other people about ourselves can reveal more than we actively and consciously chose to reveal about ourselves. The way people influence the identity and legacy of others is particularly pronounced when we consider birth – how parents and others ‘create’ an individual online before that young person has any identity in their online identity construction – and at death, when a person ceases to have agency altogether and becomes exclusively a recorded and encoded data construct. This seminar explores the limits and implications for agency, identity and data personhood in the age of Facebook.

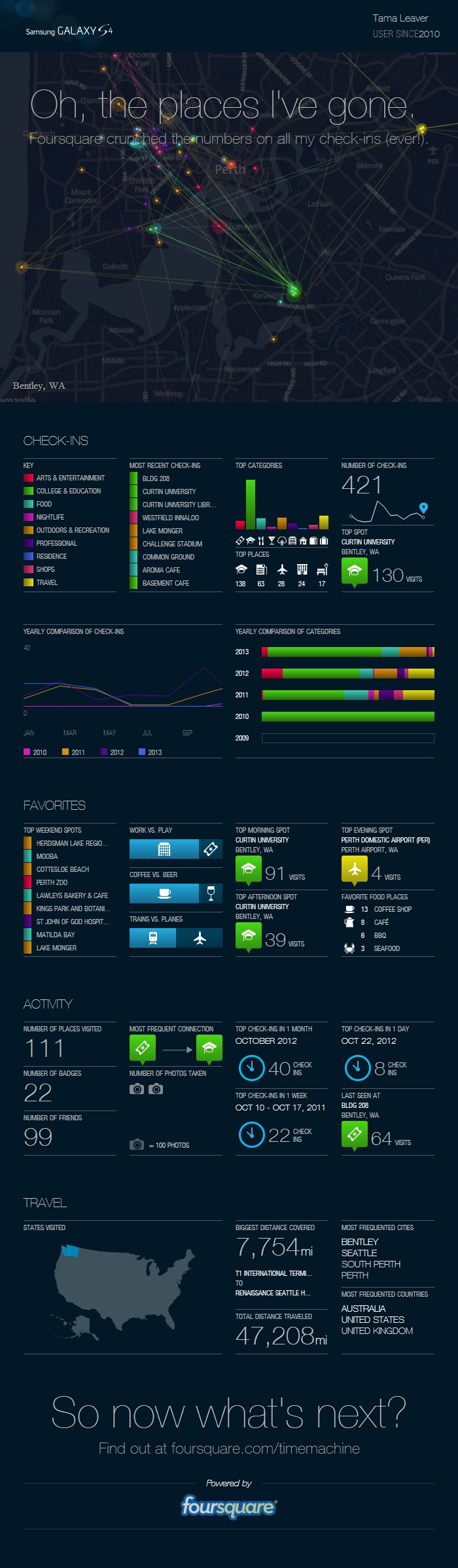

Visualising Locative Media with Foursquare’s Time Machine

I’m currently working on a chapter for the forthcoming Locative Media edited collection; the piece I’m co-writing with Clare Lloyd examines some of the pedagogical strategies that have arisen to better inform users about the data that they generate whilst using locative media in various forms (from explicit check-ins with Foursquare to less obvious locative metadata on photographs, tweets and so forth). We’ve been looking at several tools and services like PleaseRobMe.com, I Can Stalk U and Creepy which visualise the often hidden layer locative media layers of mobile devices and services.

Given this context, I was fascinated to see Foursquare’s release of their ‘Time Machine’ (deployed as a promotion for Samsung’s S4) which creates an animation and eventual infographic visualising the a user’s entire Foursquare check-in history. Since I’m very conscious of where I do and don’t use Foursquare, I was fascinated to see what sort of picture of my movements this builds. The grouping of check-ins in Perth (where I live) and the places I’ve travelled to for conferences (which is the main time I use Foursquare) was very smooth, and made my own digitised journey through the world look like a personalised network diagram. The eventual infographic produced is fairly banal, but does crunch your own Foursquare numbers. I’ve embedded mine below.

While Foursquare users are probably amongst the most aware locative media users and generators of locative data, it’s still fascinating to see what a rich and robust picture these individual points of data look like when aggregated. In line with the writing I’m doing, I can’t help wonder how people would respond to a similar sort of visualisation based on their smartphone photos or Facebook posts or some other service which is less explicit or transparent in the way locative metadata is produced and stored.

Digital Culture Links: May 21st

Links through to May 21st:

- Sensis Yellow Social Media Report 2013 [PDF] – The new Sensis Yellow Social Media Report is out (based on a survey of 937 Australians in March and April 2013), showing widespread social media use, with growth in mobile and second screen uses:

* 95% of AUstralian social media users use Facebook

* The typical Australian spends 7 hrs/wk on Facebook

* 67% of Australians access social sites on a smartphone

* 42% of Australians use social media while watching TV - A better, brighter Flickr [Flickr Blog] – Yahoo have majorly redesigned Flickr, giving new free (ad-supported) accounts 1Tb of storage, which is an awful lot of photos. The Android app is now almost identitcal to the iOS app, but the new aesthetics of the web-based version are a big change, looking more and more like every other photo-sharing service around today. Quite a few long-term Flickr users (of which I am one) have voiced a range of concerns about the design changes. Also, what this redesign means for people who’ve already paid for Pro accounts is deeply unclear on the main Flickr pages. (The Twitter account seems to suggest nothing changes.)

- Yahoo! to Acquire Tumblr / Yahoo [Yahoo News Centre] – Yahoo buys Tumblr for $1.1 billion and, in their words, “promises not to screw it up”. A clever buy for Yahoo, but it’ll be hard to integrate the rebellious/youth Tumblr userbase into the Yahoo brand.

- Introducing Photos of You [Instagram Blog] – Just in case you momentarily forgot that Facebook owns Instagram, the photo-sharing service has just added the ability to tag photos (remarkably similar to Facebook’s tagging function). Looks like Instagram needs a better map of your personal networks before they can harness it commercially.

- Follow the audience… [YouTube Blog] – May 2013 and YouTube users “are watching more than 6 billion hours of video each month on YouTube; almost an hour a month for every person on Earth and 50 percent more this year than last.”

The Social Media Contradiction: Data Mining and Digital Death

I’ve got a new article in the most recent issue of the M/C Journal entitled ‘The Social Media Contradiction: Data Mining and Digital Death’. Here’s the abstract:

Many social media tools and services are free to use. This fact often leads users to the mistaken presumption that the associated data generated whilst utilising these tools and services is without value. Users often focus on the social and presumed ephemeral nature of communication – imagining something that happens but then has no further record or value, akin to a telephone call – while corporations behind these tools tend to focus on the media side, the lasting value of these traces which can be combined, mined and analysed for new insight and revenue generation. This paper seeks to explore this social media contradiction in two ways. Firstly, a cursory examination of Google and Facebook will demonstrate how data mining and analysis are core practices for these corporate giants, central to their functioning, development and expansion. Yet the public rhetoric of these companies is not about the exchange of personal information for services, but rather the more utopian notions of organising the world’s information, or bringing everyone together through sharing.

The second section of this paper examines some of the core ramifications of death in terms of social media, asking what happens when a user suddenly exists only as recorded media fragments, at least in digital terms. Death, at first glance, renders users (or post-users) without agency or, implicitly, value to companies which data-mine ongoing social practices. Yet the emergence of digital legacy management highlights the value of the data generated using social media, a value which persists even after death. The question of a digital estate thus illustrates the cumulative value of social media as media, even on an individual level. The ways Facebook and Google approach digital death are examined, demonstrating policies which enshrine the agency and rights of living users, but become far less coherent posthumously. Finally, along with digital legacy management, I will examine the potential for posthumous digital legacies which may, in some macabre ways, actually reanimate some aspects of a deceased user’s presence, such as the Lives On service which touts the slogan “when your heart stops beating, you’ll keep tweeting”. Cumulatively, mapping digital legacy management by large online corporations, and the affordances of more focussed services dealing with digital death, illustrates the value of data generated by social media users, and the continued importance of the data even beyond the grave.

Read the rest at the M/C Journal (open access).

Incidentally, yes, one of the points in this article is already out of date as last month Google quietly launched their Inactive Account Manager. While far from perfect, this Inactive Account manager gives Google users more control over what happens to their Google stored assets after they pass away (well, actually, after they don’t log in for a specified period of time). It is, however, far from perfect.