Home » social media (Page 5)

Category Archives: social media

Digital Culture Links: December 17th

Links through to December 17th:

- The Web We Lost [Anil Dash] – Spot on: “Facebook and Twitter and Pinterest and LinkedIn and the rest are great sites, and they give their users a lot of value. … But they’re based on a few assumptions that aren’t necessarily correct. The primary fallacy that underpins many of their mistakes is that user flexibility and control necessarily lead to a user experience complexity that hurts growth. And the second, more grave fallacy, is the thinking that exerting extreme control over users is the best way to maximize the profitability and sustainability of their networks. The first step to disabusing them of this notion is for the people creating the next generation of social applications to learn a little bit of history, to know your shit, whether that’s about Twitter’s business model or Google’s social features or anything else. We have to know what’s been tried and failed, what good ideas were simply ahead of their time, and what opportunities have been lost in the current generation of dominant social networks.”

- False Posts on Facebook Undermine Its Credibility [NYTimes.com] – A reminder that Facebook’s battle against fake accounts is all about the authenticity the SELL ADVERTISERS: “For the world’s largest social network, it is an especially acute problem, because it calls into question its basic premise. Facebook has sought to distinguish itself as a place for real identity on the Web. As the company tells its users: “Facebook is a community where people use their real identities.” It goes on to advise: “The name you use should be your real name as it would be listed on your credit card, student ID, etc.” Fraudulent “likes” damage the trust of advertisers, who want clicks from real people they can sell to and whom Facebook now relies on to make money. Fakery also can ruin the credibility of search results for the social search engine that Facebook says it is building. … The research firm Gartner estimates that while less than 4 percent of all social media interactions are false today, that figure could rise to over 10 percent by 2014.”

- Android overtakes iOS in Australian usage [Ausdroid] – December 2012: “Android has been growing globally at an extremely rapid rate with statistics from November indicating that Android currently enjoys a 75% market share. In Australia this year over 67% of Smart Phone sales were Android handsets and now research analysis firm Telsyte is advising that market penetration of Android devices in Australia has finally overtaken iOS with Android now on 44% of the 10 Million mobile phones currently in use here. iOS still enjoys a 43% market share …”

- Social Media Report 2012 [Nielsen] – Nielsen’s Social Media Report 2012 provides statistical evidence of the trends for 2012, which shows the internet use, mobile use and social networking time are all up. A third of people engaging in social networking “from the bathroom”!

- Text messaging turns 20 [Technology | The Observer] – “Long ago, back before Twitter, way before Facebook, in a time when people still lifted a receiver to make a call and telephone boxes graced streets where people didn’t lock their doors, Neil Papworth, a software programmer from Reading, sent an early festive greeting to a mate. “Since mobile phones didn’t yet have keyboards, I typed the message out on a PC. It read ‘Merry Christmas’ and I sent it to Richard Jarvis of Vodafone, who was enjoying his office Christmas party at the time,” said Papworth. On 3 December 1992, he had sent the world’s first text message. Text messaging turns 20 tomorrow. More than 8 trillion were sent last year. Around 15 million leave our mobile screens every minute. There is now text poetry, text adverts and text prayers (dad@hvn, 4giv r sins) and an entire generation that’s SMS savvy. Last week saw the first major act of the text watchdog, the Information Commissioner’s Office, in fining two men £440,000 over spam texts.”

Who Do You Think You Are 2.0?

At today’s first day of the Perth CCI Symposium I presented the next section of my ongoing Ends of Identity research project as part of the Cultural Science session. I’ve attempted to use the BBC TV series Who Do You Think You Are? to explore how social media both before, during and after our lives shapes, frames and reframes who ‘we’ are in various ways.

As always, comments, questions and criticism are most welcome! ![]()

Digital Culture Links: October 29th through November 8th

Links for October 29th through November 8th:

- Backdown on internet filter plan [SMH] – YAY! “The [Australian] government has finally backed down on its plan for a controversial mandatory internet filter, and will instead rely on major service providers to block ”the worst of the worst” child abuse sites. The retreat on the filter, which Labor proposed from early in its term, comes after a strong campaign by providers. Opponents argued it would not be effective, would be costly and slow down services, and involved too much censorship. Communications Minister Stephen Conroy, who strongly argued the case for years, will announce on Friday that providers blocking the Interpol worst of the worst list ”will help keep children safe from abuse”. ”It meets community expectations, and fulfils the government’s commitment to preventing Australian internet users from accessing child-abuse material online.” The government will use its powers under the telecommunications legislation, so Senator Conroy will say a filter law will not be needed.”

- Barack Obama victory tweet becomes most retweeted ever [guardian.co.uk] – “Barack Obama has celebrated winning another term as US president by tweeting a photograph of himself hugging his wife, Michelle – which almost immediately became the most popular tweet of all time. The tweet, captioned “Four more years”, had been shared more than 400,000 times within a few hours of being posted, and marked as a favourite by more than 70,000.” (It’s now over 800,000 retweets!)

- Announcing Instagram Profiles on the Web! [Instagram Blog] – Instagram adds full web profiles for all (public) Instagram accounts. While users can still only upload from mobile devices (for now), Instagram embracing the fuller web, probably as part of the larger integration with Facebook.

- Mobile Apps Have a Ravenous Ability to Collect Personal Data [NYTimes.com] – “Angry Birds, the top-selling paid mobile app for the iPhone in the United States and Europe, has been downloaded more than a billion times by devoted game players around the world, who often spend hours slinging squawking fowl at groups of egg-stealing pigs. While regular players are familiar with the particular destructive qualities of certain of these birds, many are unaware of one facet: The game possesses a ravenous ability to collect personal information on its users. When Jason Hong, an associate professor at the Human Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, surveyed 40 users, all but two were unaware that the game was noting and storing their locations so that they could later be the targets of advertising.”

CFP: An Education In Facebook?

Along with my colleagues Mike Kent and Clare Lloyd we’re working on an edited collection about the joys, perils and uses of Facebook in higher education (of any sort). Here’s the CFP (call for papers) if you’re interested. Please feel free to distribute this post wide and far if you’d be so kind!

An Education in Facebook?

Higher Education and the World’s Largest Social NetworkEditors: Dr Mike Kent, Dr Tama Leaver and Dr Clare Lloyd, Internet Studies, Curtin University

Abstract Submission Deadline 18 January 2013

Full Chapters Due 31 May 2013

We are soliciting chapter proposals for an edited collection entitled An Education in Facebook? This edited collection will focus on the relationship between Facebook and Higher Education. Facebook first emerged in 2004 as a social network for students studying at universities in the United States. It soon grew beyond North America, and beyond the confines of student networking. Having evolved initially as a student social space the platform continues to play a prominent role in the lives of many students and staff at higher education institutions.

The collection will explore the use of Facebook the higher education environment as both a social space, and also its growing use as part of teaching and learning processes, both formally and informally. From students creating informal social groups around a course of study or particular unit, and dedicated online study groups, to the use of Facebook as a formal venue for teaching, we are seeking chapters that explore these and related areas.

Is there an appropriate place for Facebook in formal higher education? What are the tensions between private and professional spaces online for students and teachers and what are the potential dangers of unintentional overlap? What are appropriate roles and responsibilities for staff, students and institutions in relation to the social network? What are the dangers of moving important aspects of the higher education learning environment to an external company that exploits social interaction for profit? How is the shift to online learning in many institutions complemented or challenged by mobile uses of social networks, including app use on smartphones and tablets? This book will explore these and other topics interrogating the contemporary role of Facebook in Higher Education.

Some suggested topics (which are by no means exhaustive):

- · Facebook and/as/or Learning Management Systems?

- · Facebook as support network (for online and overseas learners, for example)

- · Teacher-led Facebook uses as in/formal learning

- · Student-led Facebook uses as in/formal learning

- · Case studies of Facebook implementation in formal learning

- · Informal versus formal learning online

- · Social networks and the flipped classroom

- · Context collapse

- · Privacy issues in social network use

- · Copyright issues in social network use

- · Mobile learning

- · The Facebook App in education

- · Roles and boundaries in networked learning

- · Facebook as a backchannel (either positive or disruptive)

- · The politics of ‘friending’ in staff and student relations

- · Examples of innovative Facebook integration in higher education

- · Whether Facebook has a place in formal education

- · MOOCs and Facebook

- · Comparative uses of Facebook and other online networks (eg Twitter)

Submission procedure:

Potential authors are invited to submit chapter abstract of no more than 500 words, including a title, 4 to 6 keywords, and a brief bio, by email to both Dr Mike Kent <m.kent@curtin.edu.au> and Dr Tama Leaver <t.leaver@curtin.edu.au> by 18 January 2013. (Please indicate in your proposal if you wish to use any visual material, and how you have or will gain copyright clearance for visual material.) Authors will receive a response by February 15, 2013, with those provisionally accepted due as chapters of no more than 6000 words (including references) by 31 May 2013.

About the editors:

The three editors are from the Department of Internet Studies at Curtin University. Dr Mike Kent’s research focus is on people with disabilities and their use of, and access to, information technology and the Internet. He recently co-authored the monograph Disability and New Media (Routledge, 2011). His other area a research interest is in higher education and particularly online education. Dr Tama Leaver researches online identities, digital media distribution and networked learning. He previously spent several years as a lecturer in Higher Education Development, and is currently also a Research Fellow in Curtin’s Centre for Culture and Technology. His recent book is Artificial Culture: Identity, Technology and Bodies (Routledge, 2012), and he is currently co-authoring a monograph entitled Web Presence: Staying Noticed in a Networked World. Dr Clare Lloyd specialises in mobile communication and mobile media. Her recent publications include the co-authored papers ‘Consuming apps: the Australian woman’s slow appetite for apps’ (2012); and ‘Fun and useful apps: female identity construction and social connectedness using the mobile phone’ apps’ (2012).

Facebook, Student Engagement, and the ‘Uni Coffee Shop’ Group

Here are the final slides and audio from Internet Research 13 in MediaCityUK, Salford. My last paper ‘Facebook, Student Engagement, and the ‘Uni Coffee Shop’ Group’ was presented as part of a panel about Facebook and Higher Education which also featured work by my collegues Mike Kent, Kate Raynes-Golide and Clare Lloyd.

The abstract:

While the curriculum, lecturers and tutors teaching Internet Communications via Open Universities Australia (OUA) have been engaging with students for several years using Twitter (see Leaver, 2012), in the past Facebook had been largely left alone since this was viewed as a more casual space where students might interact with each other, but not with teaching staff. However, in the last two years, more and more students have created groups to use Facebook as a discussion space about their units, often attracting a significant proportion of students from that unit. While these groups are important, of even more interest is the establishment of the group called the ‘Uni Coffee Shop’. Unlike the unit-specific groups, the Coffee Shop group, established by two Internet Communications students but open to anyone studying online via OUA, affords group support, social connectivity and a persistent online space for conversation which does not disappear or grow stagnant when students complete a specific unit.

This paper will outline an investigation into the effectiveness of the Uni Coffee Shop group as a student-created space for engagement and informal learning. Three modes of inquiry were used: a textual analysis of the common topics of discussion in the group over several months; a quantitative survey of members of the Coffee Shop group; and several follow-up qualitative interviews with Coffee Shop group members, including the two students who administer the group. In addition, the paper includes the perspectives of teaching staff who have been invited to join the group by students and who, at times, answer specific questions and engage with students in a less formal manner. In detailing the results of these mechanisms, this paper will argue that fostering student-run spaces of engagement using Facebook can be a very effective means to create spaces of engagement and informal learning (Krause & Coates, 2008; Greenhow & Robelia, 2009); the support students give each other can persist over the length of an entire degree; and teaching staff engaging with students in their space, often on their terms, can create a better rapport and a stronger sense of connectivity over the length of a student’s entire degree (and potentially beyond). A student-run Facebook group also provide a space where teaching staff and students can interact using the affordances of Facebook without staff having to explicitly ‘friend’ students (something many staff are reluctant to do for a range of reasons).

References

Greenhow, C., & Robelia, B. (2009). Informal learning and identity formation in online social networks. Learning, Media and Technology, 34(2), 119 – 140.

Krause, K., & Coates, H. (2008). Students’ engagement in first‐year university. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5), 493-505. doi:10.1080/02602930701698892

Leaver, T. (2012). Twittering informal learning and student engagement in first-year units. In A. Herrington, J. Schrape, & K. Singh (Eds.), Engaging students with learning technologies (pp. 97–110). Perth, Australia: Curtin University. Retrieved from http://espace.library.curtin.edu.au/R?func=dbin-jump-full&local_base=gen01-era02&object_id=187303

Global Media Distribution and the Tyranny of Digital Distance

Here are the slides and audio from my paper ‘Global Media Distribution and the Tyranny of Digital Distance’ presented on Saturday, 20 October 2012 at Internet Research 13 in MediaCityUK, Salford:

The paper drifted somewhat from the original abstract, but in a nutshell asks why it is taking television networks so long to escape the tyranny of digital distance (in this instance embodied by the national delays in re-broadcasting overseas-produced television shows). I look at several examples, including the recent Olympics broadcasts, as well as the deep-seated resistance from commercial TV networks in Australia. I conclude following Mark Scott that the future is already here, in the visage of young viewers and Peppa Pig fans who will never know the broadcast schedule and that these are the viewers for whom networks should be preparing to entertain today.

News and Trolls: Olympic Games Coverage in the Twenty-First Century

I’m at MediaCityUK in Salford for the annual Association of Internet Researchers conference (IR13) and today gave the first of three papers I’m involved with. Today’s was part of a great pre-conference session organised by Holly Kruse. My talk was called “News and Trolls: Olympic Games Coverage in the Twenty-First Century”; it’s very much a work in progress, but the slides are embedded below in case anyone’s interested.

Sadly I didn’t record the audio, so the slides may lack contextualisation.

Digital Culture Links: October 7th

Links for September 25th through October 7th:

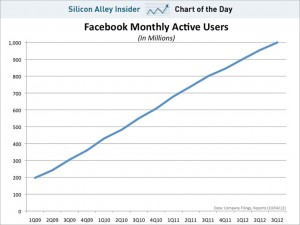

Facebook surpasses one billion users as it tempts new markets [BBC News] – "Facebook now has more than one billion people using it every month, the company has said. The passing of the milestone was announced by founder Mark Zuckerberg on US television on Thursday. The company said that those billion users were to date responsible for 1.13 trillion "likes", 219 billion photos and 17 billion location check-ins. The site, which was launched in 2004, is now looking towards emerging markets to build its user base further. "If you're reading this: thank you for giving me and my little team the honor of serving you," Mr Zuckerberg wrote in a status update. "Helping a billion people connect is amazing, humbling and by far the thing I am most proud of in my life." Statistics released to coincide with the announcement revealed there were now 600 million users accessing the site via a mobile device – up 48 million from 552 million in June this year." [Chart Source]

Facebook surpasses one billion users as it tempts new markets [BBC News] – "Facebook now has more than one billion people using it every month, the company has said. The passing of the milestone was announced by founder Mark Zuckerberg on US television on Thursday. The company said that those billion users were to date responsible for 1.13 trillion "likes", 219 billion photos and 17 billion location check-ins. The site, which was launched in 2004, is now looking towards emerging markets to build its user base further. "If you're reading this: thank you for giving me and my little team the honor of serving you," Mr Zuckerberg wrote in a status update. "Helping a billion people connect is amazing, humbling and by far the thing I am most proud of in my life." Statistics released to coincide with the announcement revealed there were now 600 million users accessing the site via a mobile device – up 48 million from 552 million in June this year." [Chart Source]- Jill Meagher | Trial by Social Media A Worry, Experts Say [The Age] – "The case of Jill Meagher has had the country talking, particularly on social media, but now that someone has been charged it's time to stop being specific, experts say. Jill Meagher was mentioned on social media, both Twitter and Facebook, every 11 seconds early this morning. And the CCTV footage which showed her walking on Sydney Road on the morning she disappeared was shared on the same platforms about 7500 times within two hours … .A Facebook hate group against the accused in the Meagher case has already attracted almost 18,000 "likes". Victoria Police has posted a message on its Facebook page this morning warning users of their legal responsibilities in posting and reminding that "it is inappropriate to post speculation or comments about matters before the courts Thomas Meagher, Jill's husband, today urged people to consider what they posted on Twitter and Facebook."

- Your YouTube original videos now available in Google Takeout [Google Data Liberation] – YouTube just became a lot more interesting as a storage space for video, not just a distribution platform: "Your Takeout menu is growing. Today's entrée: YouTube videos. Previously, you've been able to download individual transcoded videos from your YouTube Video Manager. But starting today, you also have a more efficient way to download your videos from YouTube. With Google Takeout, you can download all of the original videos that you have uploaded in a few simple clicks. No transcoding or transformation — you’ll get exactly the same videos that you first uploaded. Your videos in. Your videos out."

- Rupert Murdoch backs down in war with ‘parasite’ Google – Telegraph – "News Corporation plans to reverse an earlier decision to stop articles from its quality papers, such as The Times and The Sunday Times, from featuring in Google’s listings. The effort to stop users from accessing content for free will be watered down, with Google featuring stories in search rankings from next month. The move comes amid fears that the newspapers’ exclusion is limiting their influence and driving down advertising revenues. Sources claim the change was a “marketing exercise”. In the past, Mr Murdoch has lambasted Google as a “parasite” and a “content kleptomaniac” because it only allows companies to feature in search rankings if users are able to click through to at least one page without paying."

- Google Play hits 25 billion downloads [Official Android Blog] – Google announces that the Google Play store now offers over 675,000 apps and games and that there have been over 25 billion individual app installations to date. (September 2012).

- Facebook raises fears with ad tracking [CNN.com] – "Facebook is working with a controversial data company called Datalogix that can track whether people who see ads on the social networking site end up buying those products in stores.

Amid growing pressure for the social networking site to prove the value of its advertising, Facebook is gradually wading into new techniques for tracking and using data about users that raise concerns among privacy advocates.[…] Datalogix has purchasing data from about 70m American households largely drawn from loyalty cards and programmes at more than 1,000 retailers, including grocers and drug stores. By matching email addresses or other identifying information associated with those cards against emails or information used to establish Facebook accounts, Datalogix can track whether people bought a product in a store after seeing an ad on Facebook. The emails and other identifying information are made anonymous and collected into groups of people who saw an ad and people who did not." - Facebook Is Now Recording Everyone You Stalk [Gizmodo Australia] – Facebook has announced that they will now record your Facebook search history; every time you search for someone's name, that information will be stored, accessible as part of your 'Activity Log'. The search entries are individually delectable and only visible to you (and Facebook) but the existence of a Facebook search history is a sure sign that Facebook sees real value in recording – and thus data crunching and somehow monetizing – your search history.

Digital Culture Links: August 22nd

Links – catching up – through to August 22nd:

- Instagram 3.0 – Photo Maps & More [Instagram Blog]– Instagram releases a substantial new update for iOS and Android, adding a new photo maps feature. If the user chooses to do so, the photo maps places all geotagged photos onto an interactive map of the globe which can be navigated by Instagram users’ contacts.

Instagram 3.0 – Photo Maps Walkthrough from Instagram on Vimeo.While the maps function is being rolled out with very clear warnings about revealing locations publicly – with tools to remove geotags from some, groups or all photos – this rollout will no doubt remind (and shock many) users that the geographic tags on their photos mean that these aren’t just photos – they’re important and complex assemblages of data that can be reused and repurposed in a variety of ways.

- Google to push pirate sites down search results [BBC – Newsbeat] – “Google is changing the way it calculates search results in an effort to make sure legal download websites appear higher than pirate sites. The world’s biggest search engine announced the change in a blog post on its website. The move has been welcomed by record companies in the UK and Hollywood film studios. Movie and music firms have complained in the past that Google should have been doing more to fight piracy. They say searching for an artist, song or film often brings up pages of illegal sites, making it hard to find a place to download a legal version. From next week, search results will take into account the number of “valid copyright removal notices”. Sites with more notices will rank lower, although Google has not said what it considers a valid notice.”

- Gotye – Somebodies: A YouTube Orchestra [YouTube]– Fantastic remix by Gotye, using a huge range of fan remixes of Somebody that I Used to Know and mashing them together. Comes with a full credits list, too: http://gotye.com/reader/items/original-videos-used-in-somebodies-a-youtube-orchestra.html (A great example for Web Media 207.)

- Facebook removes ‘racist’ page in Australia [BBC News] – “A Facebook page that depicted Aboriginal people in Australia as drunks and welfare cheats has been removed after a public outcry. The Aboriginal Memes page had allowed users to post jokes about indigenous people. An online petition calling for the removal of “the racist page” has generated thousands of signatures. The government has also condemned it. The page’s creator is believed to be a 16-year-old boy in Perth, reports say. “We recognise the public concern that controversial meme pages that Australians have created on Facebook have caused,” Facebook said in a statement to local media. A meme is an idea that spreads through the internet.”

- Twitter ‘sorry’ for suspending Guy Adams as NBC withdraws complaint [Technology | guardian.co.uk] – “Twitter on Tuesday reinstated the account of a British journalist it suspended for publishing the email address of an executive at NBC, which had been attracting a significant amount of incoming fire over its Olympics coverage. The incident has not done Guy Adams of the Independent much harm. Apart perhaps from a little hurt pride, he has returned to the twittersphere with tens of thousands of new followers. For NBC, it was another blow to its already battered reputation over its coverage of the London Olympic Games. But Twitter found itself in a deeply unfamiliar situation: as the subject of one of the firestorms of indignation that characterises the platform, but which are usually directed at others.”

- Murdoch’s tablet The Daily lays off nearly a third of its staff [Media | guardian.co.uk] – “The Daily, Rupert Murdoch’s tablet newspaper, has laid off close to a third of its staff just 18 months after its glitzy launch. Executives at the News Corp-owned title told its 170 employees on Tuesday that 50 of them would be let go. Sources told the Guardian that security staff were brought onto the Daily’s editorial floor at News Corp in New York to escort the laid-off employees out of the building. Earlier this month the paper’s editor-in-chief Jesse Angelo denied reports that the media giant had put the title “on watch” and was considering closing it. In a statement Tuesday Angelo said the title was dropping its opinion section and would be taking sports coverage from Fox Sports, also part of News Corp, and other partners. In another cost-saving move the title will also stop producing pages that can be read vertically and horizontally on a tablet, sticking to straight up and down.”

- If Twitter doesn’t reinstate Guy Adams, it’s a defining moment [Dan Gillmor | Comment is free | guardian.co.uk] – “Once again, we’re reminded of a maxim when it comes to publishing on other people’s platforms: we publish at their sufferance. But there’s a corollary: When they take down what we publish, they take an enormous risk with their own futures.

This time, Twitter has suspended the account of a British journalist who tweeted the corporate email address of an NBC executive. The reporter, Guy Adams of the Independent, has been acerbic in his criticisms of NBC’s (awful) performance during the Olympics in London. Adams has posted his correspondence with Twitter, which claims he published a private email address. It was nothing of the kind, as many, including the Deadspin sports blog, have pointed out. … What makes this a serious issue is that Twitter has partnered with NBC during the Olympics. And it was NBC’s complaint about Adams that led to the suspension. That alone raises reasonable suspicions about Twitter’s motives.”

Digital Culture Links: July 25th through July 30th

Links for July 25th through July 30th:

- Apple, Microsoft refuse to appear before IT pricing inquiry [The Age] – “A[n Australian] parliamentary committee wants to force computer giant Apple to appear before it after members became frustrated with the company’s refusal to co-operate. Hearings into the pricing of software and other IT-related material such as games and music downloads will begin in Sydney tomorrow but neither Apple nor Microsoft will appear. ”Some of the big names in IT have taken local consumers for a ride for years but when legitimate questions are asked about their pricing, they disappear in a flash,” Labor MP and committee member Ed Husic told Fairfax Media. ”Within our growing digital economy, there are reasonable questions to be answered by major IT companies on their Australian pricing. These companies would never treat US consumers in this way.” Both Microsoft and Adobe provided submissions to the inquiry.”

- Don’t tweet if you want TV, London fans told [The Age] – “Sports fans attending the London Olympics were told on Sunday to avoid non-urgent text messages and tweets during events because overloading of data networks was affecting television coverage. Commentators on Saturday’s men’s cycling road race were unable to tell viewers how far the leaders were ahead of the chasing pack because data could not get through from the GPS satellite navigation system travelling with the cyclists. It was particularly annoying for British viewers, who had tuned in hoping to see a medal for sprint king Mark Cavendish. Many inadvertently made matters worse by venting their anger on Twitter at the lack of information. An International Olympic Committee spokesman said the network problem had been caused by the messages sent by the hundreds of thousands of fans who lined the streets to cheer on the British team. “Of course, if you want to send something, we are not going to say ‘Don’t, you can’t do it’,… “

- Olympics 2012, Sir Tim Berners Lee and Open Internet [Cerebrux] – Great to see the 2012 London Olympics celebrating World Wide Web inventor, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. “Flash forward to last night, he was honored as the ‘Inventor of the World Wide Web’ at the 2012 Summer Olympics opening ceremony. Berners-Lee is revealed in front of a computer keyboard into which he types a message, which is then rendered in lights in the stands of Olympic Stadium: “This is for everyone.” and a message simultaneously appeared on his Twitter account: Tim Berners-Lee@timberners_lee This is for everyone #london2012 #oneweb #openingceremony @webfoundation @w3c

28 Jul 12. A great quote that resembles the openness and the fact that some things should belong to humanity.” - The Rise of the “Connected Viewer” [Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project] – “Half of all adult cell phone owners now incorporate their mobile devices into their television watching experiences. These “connected viewers” used their cell phones for a wide range of activities during the 30 days preceding our April 2012 survey:

- 38% of cell owners used their phone to keep themselves occupied during commercials or breaks in something they were watching

- 23% used their phone to exchange text messages with someone else who was watching the same program in a different location

- 22% used their phone to check whether something they heard on television was true

- 20% used their phone to visit a website that was mentioned on television

- 11% used their phone to see what other people were saying online about a program they were watching, and 11% posted their own comments online about a program they were watching using their mobile phone

- Taken together, 52% of all cell owners are “connected viewers”—meaning they use their phones while watching television …”

- RIAA: Online Music Piracy Pales In Comparison to Offline Swapping [TorrentFreak] – “A leaked presentation from the RIAA shows that online file-sharing isn’t the biggest source of illegal music acquisition in the U.S. The confidential data reveals that 65% of all music files are “unpaid” but the vast majority of these are obtained through offline swapping. […] In total, 15 percent of all acquired music (paid + unpaid) comes from P2P file-sharing and just 4 percent from cyberlockers. Offline swapping in the form of hard drive trading and burning/ripping from others is much more prevalent with 19 and 27 percent respectively. This leads to the, for us, surprising conclusion that more than 70% of all unpaid music comes from offline swapping. The chart is marked “confidential” which suggests that the RIAA doesn’t want this data to be out in the open. This is perhaps understandable since the figures don’t really help their crusade against online piracy.”

- Robin Hood Airport tweet bomb joke man wins case [BBC News] – Finally: “A man found guilty of sending a menacing tweet threatening to blow up an airport has won a challenge against his conviction. Paul Chambers, 28, of Northern Ireland, was found guilty in May 2010 of sending a “menacing electronic communication”. He was living in Doncaster, South Yorkshire, when he tweeted that he would blow up nearby Robin Hood Airport when it closed after heavy snow.

After a hearing at the High Court in London his conviction was quashed.” - The Instagram Community Hits 80 Million Users [Instagram Blog] – As of July 2012, after finally launching an Android app, and being purchased by Facebook, Instagram has 80 million registered users, who’ve posted cumulatively more than 4 billion photos.

- Music stars accuse Google of helping pirates rip off material [WA Today] – “LONDON: Roger Daltry of the Who and Brian May of Queen are among rock and pop stars who publicly attacked search engines such as Google for helping users get access to pirated copies of their music. Elton John, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin have also signed a letter to The Daily Telegraph in London calling for more action to tackle the illegal copying and distribution of music. Other signatories include the producer and creator of The X Factor, Simon Cowell. The letter, which will also be sent to the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, this week, highlighted the role that search engines can play in giving people access to illegal copies. Search engines must ”play their part in protecting consumers and creators from illegal sites”, the signatories said, adding that broadband companies and online advertisers must also do more to prevent piracy.”