Home » Ponderings

Category Archives: Ponderings

Coroner finds social media contributed to 14-year-old Molly Russell’s death. How should parents and platforms react?

Tama Leaver, Curtin University

Last week, London coroner Andrew Walker delivered his findings from the inquest into 14-year-old schoolgirl Molly Russell’s death, concluding she “died from an act of self harm while suffering from depression and the negative effects of online content”.

The inquest heard Molly had used social media, specifically Instagram and Pinterest, to view large amounts of graphic content related to self-harm, depression and suicide in the lead-up to her death in November 2017.

The findings are a damning indictment of the big social media platforms. What should they be doing in response? And how should parents react in light of these events?

Social media use carries risk

The social media landscape of 2022 is different to the one Molly experienced in 2017. Indeed, the initial public outcry after her death saw many changes to Instagram and other platforms to try and reduce material that glorifies depression or self-harm.

Instagram, for example, banned graphic self-harm images, made it harder to search for non-graphic self-harm material, and started providing information about getting help when users made certain searches.

BBC journalist Tony Smith noted that the press team for Instagram’s parent company Meta requested that journalists make clear these sorts of images are no longer hosted on its platforms. Yet Smith found some of this content was still readily accessible today.

Also, in recent years Instagram has been found to host pro-anorexia accounts and content encouraging eating disorders. So although platforms may have made some positive changes over time, risks still remain.

That said, banning social media content is not necessarily the best approach.

What can parents do?

Here are some ways parents can address concerns about their children’s social media use.

Open a door for conversation, and keep it open

It’s not always easy to get young people to open up about what they’re feeling, but it’s clearly important to make it as easy and safe as possible for them to do so.

Research has shown creating a non-judgemental space for young people to talk about how social media makes them feel will encourage them to reach out if they need help. Also, parents and young people can often learn from each other through talking about their online experiences.

Try not to overreact

Social media can be an important, positive and healthy part of a young person’s life. It is where their peers and social groups are found, and during lockdowns was the only way many young people could support and talk to each other.

Completely banning social media may prevent young people from being a part of their peer groups, and could easily do more harm than good.

Negotiate boundaries together

Parents and young people can agree on reasonable rules for device and social media use. And such agreements can be very powerful.

They also present opportunities for parents and carers to model positive behaviours. For example, both parties might reach an agreement to not bring their devices to the dinner table, and focus on having conversations instead.

Another agreement might be to charge devices in a different room overnight so they can’t be used during normal sleep times.

What should social media platforms do?

Social media platforms have long faced a crisis of trust and credibility. Coroner Walker’s findings tarnish their reputation even further.

Now’s the time for platforms to acknowledge the risks present in the service they provide and make meaningful changes. That includes accepting regulation by governments.

More meaningful content moderation is needed

During the pandemic, more and more content moderation was automated. Automated systems are great when things are black and white, which is why they’re great at spotting extreme violence or nudity. But self-harm material is often harder to classify, harder to moderate and often depends on the context it’s viewed in.

For instance, a picture of a young person looking at the night sky, captioned “I just want to be one with the stars”, is innocuous in many contexts and likely wouldn’t be picked up by algorithmic moderation. But it could flag an interest in self-harm if it’s part of a wider pattern of viewing.

Human moderators do a better job determining this context, but this also depends on how they’re resourced and supported. As social media scholar Sarah Roberts writes in her book Behind the Screen, content moderators for big platforms often work in terrible conditions, viewing many pieces of troubling content per minute, and are often traumatised themselves.

If platforms want to prevent young people seeing harmful content, they’ll need to employ better-trained, better-supported and better-paid moderators.

Harm prevention should not be an afterthought

Following the inquest findings, the new Prince and Princess of Wales astutely tweeted “online safety for our children and young people needs to be a prerequisite, not an afterthought”.

For too long, platforms have raced to get more users, and have only dealt with harms once negative press attention became unavoidable. They have been left to self-regulate for too long.

The foundation set up by Molly’s family is pushing hard for the UK’s Online Safety Bill to be accepted into law. This bill seeks to reduce the harmful content young people see, and make platforms more accountable for protecting them from certain harms. It’s a start, but there’s already more that could be done.

In Australia the eSafety Commissioner has pushed for Safety by Design, which aims to have protections built into platforms from the ground up.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.![]()

Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Facebook is merging Messenger and Instagram chat features. It’s for Zuckerberg’s benefit, not yours

Tama Leaver, Curtin University

Tama Leaver, Curtin University

Facebook Messenger and Instagram’s direct messaging services will be integrated into one system, Facebook has announced.

The merge will allow shared messaging across both platforms, as well as video calls and the use of a range of tools drawn from both platforms. It’s currently being rolled out across countries on an opt-in basis, but hasn’t yet reached Australia.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced plans in March last year to integrate Messenger, Instagram Direct and WhatsApp into a unified messaging experience.

At the crux of this was the goal to administer end-to-end encryption across the whole messaging “ecosystem”.

Ostensibly, this was part of Facebook’s renewed focus on privacy, in the wake of several highly publicised scandals. Most notable was its poor data protection that allowed political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica to steal data from 87 million Facebook accounts and use it to target users with political ads ahead of the 2016 US presidential election.

In a statement released yesterday on the new merge, Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri and Messenger vice president Stan Chudnovsky wrote:

… one out of three people sometimes find it difficult to remember where to find a certain conversation thread. With this update, it will be even easier to stay connected without thinking about which app to use to reach your friends and family.

While that may seem harmless, it’s likely Facebook is actually attempting to make its apps inseparable, ahead of a potential anti-trust lawsuit in the US that may try to see the company sell Instagram and WhatsApp.

Together, with Facebook, 24/7

The Messenger/Instagram Direct merge will extend to features rolled out during the pandemic, such as the “Watch Together” tool for Messenger. As the name suggests, this lets users watch videos together in real time. Now, both Messenger and Instagram users will be able to use it, regardless of which app they’re on.

With the integration, new privacy challenges emerge. Facebook has already acknowledged this. And these challenges will present despite Facebook’s overarching privacy policy applying to every app in its app “family”.

For example, in the new merged messaging ecosystem, a user you previously blocked on Messenger won’t automatically be blocked on Instagram. Thus, the blocked person will be able to once again contact you. This could open doors to a plethora of unexpected online abuse.

Why this is good for Mark Zuckerberg

This first step – and Facebook’s full roadmap for the encrypted integration of WhatsApp, Instagram Direct and Messenger – has three clear outcomes.

Firstly, end-to-end encryption means Facebook will have complete deniability for anything that travels across its messaging tools.

It won’t be able to “see” the messages. While this might be good from a user privacy perspective, it also means anything from bullying, to scams, to illegal drug sales, to paedophilia can’t be policed if it happens via these tools.

This would stop Facebook being blamed for hurtful or illegal uses of its services. As far as moderating the platform goes, Facebook would effectively become “invisible” (not to mention moderation is expensive and complicated).

This is all great news for Mark Zuckerberg, especially as Facebook stares down the barrel of potential anti-trust litigation.

Secondly, once the apps are merged, functionally they will no longer be separate platforms. They will still exist as separate apps with some separate features, but the vast amount of personal data underpinning them will live in one giant, shared database.

Deeper data integration will let Facebook know users more intimately. Moreover, it will be able to leverage this new insight to target users with more advertising and expand further.

Finally, and perhaps most concerning, is that by integrating its apps Facebook could legitimately respond to anti-trust lawsuits by saying it can’t separate Instagram or WhatsApp from the main Facebook platform – because they’re the same thing now.

And if they can’t be separated, there’s no way Facebook could sell Instagram or WhatsApp, even if it wanted to.

100 billion messages a day

The messaging traffic across Facebook’s platforms is vast, with more than 100 billion messages sent daily. And this has only increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With the sheer size of its user database, Facebook continues to either purchase, or squash, its competition. Concerns about the company being a monopoly aren’t without merit.

Researchers and founding Facebook employees have called to have the company split up – and for Instagram and Whatsapp to become separate again.

Just a few months ago, Facebook released its Instagram-housed tool Reels which bears a striking resemblance to TikTok, another social app sweeping the globe.

It seems this is just another example of Facebook trying to use the sheer size of its network to stifle growing competition, aided (perhaps unwittingly) by Donald Trump’s anti-China sentiment.

If competition is important to encouraging innovation and diversity, then the newest development from Facebook discourages both these things. It further entrenches Facebook and its services into the lives of consumers, making it harder to pull away. And this certainly isn’t far from monopolistic behaviour.

![]()

Tama Leaver, Associate Professor in Internet Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tips for Giving & Receiving Feedback on Journal Articles (via Peer Review)

I was part of a great WA Communication Culture Media panel today on the theme of feedback and was specifically asked to comment on receiving and giving feedback on journal articles (mainly via peer review). It was a great and wide-ranging conversation, and clearly applicable well beyond the immediate audience, so I thought I’d post my tips for journal feedback here.

I was part of a great WA Communication Culture Media panel today on the theme of feedback and was specifically asked to comment on receiving and giving feedback on journal articles (mainly via peer review). It was a great and wide-ranging conversation, and clearly applicable well beyond the immediate audience, so I thought I’d post my tips for journal feedback here.

Receiving Feedback via Peer Reviews

[1] Be Humble. Your peer reviewers are almost always providing free labour when undertaking peer reviews. Sometimes they’ve been mentored and have a great and encouraging system for giving feedback that makes it easy to receive. Often, however, they’re replicating a model of peer review that’s more combative. Either way, most peer reviews (even the dreaded ‘Reviewer 2’) have something useful in them. Be humble and try and find those useful points. That doesn’t mean taking all criticism to heart. Nor does it mean your peer reviews are necessarily right. Be they do exist, and someone took the time to write them, so try and find what’s valuable in them, even if you have to read around sometimes unnecessarily combative language and framing.

[2] Know The Limits of What You Are Willing to Change. Often peer reviews will suggest an article demonstrate more familiarity with a field, or engage with more specific work. Even if this feels unnecessary, it’s probably worth doing. However, if a review rejects your overall argument, or frame, it’s good to have decided how much you are willing to change, and how much you won’t. How important is it to you or your career to publish in this journal? Which line don’t you want to cross in terms of changing your framework or argument? If the reviews ask too much, and the editors want those reviews taken as a blueprint for change, then sometimes it’s okay to pull the article and find somewhere more appropriate. Just know where that line is for you. Peers are humans, too; sometimes their reviews do ask more than is reasonable for what you want an article to achieve.

[3] Use Your Response Meaningfully (& Follow the Instructions for Revision!). After you’ve received peer reviews and are invited to revise your article, you’ll usually be asked to provide a summary of what you’ve changed in the article. This is also your chance to dialogue with the editors and peer reviewers (if it’s going to have a second round of review). If your reviews have been contradictory, or you’ve deliberately not followed specific suggestions, explain your rationale here. Editors and reviewers aren’t machines, and will often agree with your thinking (not always, I should add, but often). Equally, if you get specific instructions – for example, to use tracked changes or highlighting to immediately make alterations obvious – then follow these precisely! For editors and reviewers, it can be very frustrating trying to see what’s been changed if that’s not clearly flagged!

[4] Be timely. While reviews and revisions should be taken seriously, and everyone has many things to do, it’s best to fit these revisions in as soon as you can. This expedites things from the journal’s perspective and your own! The best articles are finished ones!

Giving Feedback and Writing Peer Reviews

[1] Be timely. Peer review is usually free labour provided by scholars. Know how much you can reasonably and meaningfully review in a given year. But once you accept the role as reviewer, please stick to the requested reviewing timeline if you possibly can. Journal editors struggle to find enough peer reviewers, and hate having to chase reviewers for late reviews. More to the point, it can lead to stagnation in scholarship if an article takes 6 or 9 months for the first round of review. So, only commit if you know you’ve got time, but once you’re committed to a peer review, make the time to do it.

[2] Be generous. Generosity doesn’t mean accepting articles that aren’t ready for publication. It does mean, framing all feedback constructively and, ideally, positively. If you’re rejecting a paper outright, giving the author a roadmap to improve that article and become a better scholar is still important (indeed, perhaps more important than the acceptances or minor review recommendations). Equally, don’t be the person who responds by saying ‘Well, if I was writing on this topic I’d have done it this way.’ You didn’t write it. Does the article add to scholarship on its own terms? Academia has far too many versions of combative review. Peer reviews can always be generous of spirit, even if they’re ultimately not recommending publication. Reviews aren’t just reviews; they’re a form of mentorship.

[3] Be precise. The most frustrating comments (wearing either my editor or author hat) are the ones that make broad statements without being precise. ‘The argumentation is unclear.’ ‘Needs to engage with the core scholars in X field.’ If the argument needs work, try and indicate where. If there are 4 key scholars you think an article needs to dialogue with, mention their names. While it might not suit everyone, I’ve started giving all peer review feedback as a series of specific and clear numbered points; a checklist of changes, essentially. In my opinion, a clear and precise roadmap to what you think would make the article better is the most useful thing a peer review can provide.

Feedback Doesn’t Stop Once an Article or Publication is Out!

[1] Share Widely! Most journals will let an author archive a pre-print (ie the submitted version of an article, before peer review) and, after a time delay, a post-print (the peer reviewed but not paginated version). Use this to populate your open access institutional repository, personal website archive, or elsewhere. If your journal allows it, post to academic social networks like Academia.edu and ResearchGate.

[2] Publicise on Social Media. Increasingly, academics find out about each other’s work through social networks as much as searches and alerts. If you’re using Twitter or Facebook or other online platforms to engage with your academic peers, then share links to your work there. Point to the pre-prints when they’re posted, and point to the final published versions once they’re up online. Celebrate your publications, and celebrate (and retweet) great work by your peers and colleagues! If you get meaningful questions, comments or offers of collaboration, that’s pretty decent feedback, too!

[3] Engage Beyond the Ivory Tower. One of the skills scholars often lack is translating their work for audiences beyond academia. Yet press releases, or writing short summary pieces, such as those in The Conversation, can make your work far more accessible, and ensure it can have the widest possible engagement and impact. This sort of engagement does take some work, but if you’ve just written the most amazing article ever, and you want an audience, then engaging publicly will make your work available to the widest audience.

CFP: Gaming Disability: Disability perspectives on contemporary video games

Call For Papers:

Gaming Disability: Disability perspectives on contemporary video games

Edited by Dr Katie Ellis, Dr Mike Kent & Dr Tama Leaver

Internet Studies, Curtin University

Abstracts Due 15 February 2017

Video games are a significant and still rapidly expanding area of popular culture. Media Access Australia estimated that in 2012 some twenty percent of gamers were people with a disability, yet, the relationship between video gaming, online gaming and disability is an area that until now has been largely under explored. This collection seeks to fill that gap. We are looking for scholars from both disability studies and games studies, along with game developers and innovators and disability activists and other people with interest in this area to contribute to this edited collection.

We aim to highlight the history of people with disabilities participating in video games and explore the contemporary gaming environment as it relates to disability. This exploration takes place in the context of the changing nature of gaming, particularly the shift from what we might consider traditional desktop computer mediation onto mobile devices and augmented reality platforms. The collection will also explore future possibilities and pitfalls for people with disabilities and gaming.

Areas of interest that chapters might address include

- Disability narratives and representation in gaming

- Accessibility of gaming for people with disabilities

- Mods, hacks and alterations to games and devices for and by people with disabilities

- Augmented reality games and disability

- Disability gaming histories

- Mobile gaming platforms and disability

- Specific design elements (such as sound) in terms of designing accessible games

- Gaming, television and disability

- Future directions for disability and gaming

Submission procedure:

Potential authors are invited to submit chapter abstracts of no more than 500 words, including a title, 4 to 6 keywords, and a brief bio, by email to Dr Mike Kent <m.kent@curtin.edu.au> by 15 February 2017. (Please indicate in your proposal if you wish to use any visual material, and how you have or will gain copyright clearance for visual material.) Authors will receive a response by 15 March 2016, with those provisionally accepted due as chapters of approximately 6000 words (including references) by 15 June 2016. If you would like any further information, please contact Mike Kent.

About the editors:

The editors are all from the Department of Internet Studies at Curtin University and have a history of successfully publishing edited collections in the areas of and gaming, disability, and new media.

Dr Katie Ellis is an Associate Professor and Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Internet Studies at Curtin University. Her research focuses on disability and the media extending across both representation and active possibilities for social inclusion. Her books include Disability and New Media (2011 with Mike Kent), Disabling Diversity (2008), Disability, Ageing and Obesity: Popular Media Identifications (2014; with Debbie Rodan & Pia Lebeck), Disability and the Media (2015; with Gerard Goggin), Disability and Popular Culture (2015) and her recent edited collection with Mike Kent Disability and Social Media: Global Perspectives (2017).

Dr Mike Kent is a senior lecturer and Head of Department in the Department of Internet Studies at Curtin University. Mike’s research focus is on people with disabilities and their use of, and access to, information communication technology and the Internet. His other area of research interest is in higher education and particularly online education, as well as online social networking platforms. His book, with Katie Ellis, Disability and New Media was published in 2011 and his edited collection, with Tama Leaver, An Education in Facebook? Higher Education and the World’s Largest Social Network, was released in 2014. His latest edited collection, with Katie Ellis, Disability and Social Media: Global Perspectives is available 2017, along with his forthcoming edited collections Massive Open Online Courses and Higher Education: What went right, what went wrong and where to now, with Rebecca Bennett and Chinese Social Media Today: Critical Perspectives with Katie Ellis and Jian Xu.

Dr Tama Leaver is an Associate Professor in the Department of Internet Studies at Curtin University. He researches online identities, digital media distribution and networked learning. He previously spent several years as a lecturer in Higher Education Development, and is currently also a Research Fellow in Curtin’s Centre for Culture and Technology. His book Artificial Culture: Identity, Technology and Bodies was released through Routledge in 2012 and his edited collections An Education in Facebook? Higher Education and the World’s Largest Social Network, with Mike Kent, was released in 2014 through Routledge, and Social, Casual and Mobile Games: The Changing Gaming Landscape, with Michele Wilson, was released through Bloomsbury Academic in 2016.

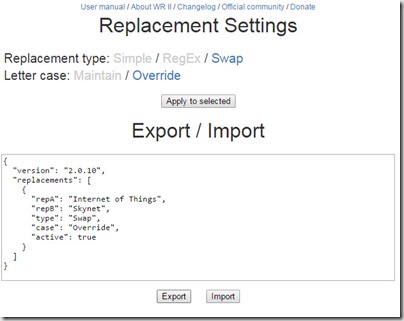

Replace every mention of internet of things with skynet (in chrome)

For Kath: How to replace every mention of “Internet of Things” with “Skynet” and vice versa in your Chrome browser.

- In Chrome, install the Word Replacer 2 plugin.

- Click the plugin settings, select settings.

- Click ‘new’ on the left and enter your item name (I’ve called mine “Internet of Things” in the left box, “Skynet” in the box next to it on the right.)

- At the top of the right pane, select ‘Swap’ (or just ‘Simple’ if you just want “internet of things” replaced, but IOT mentions of Skynet turing into Internet of Things).

- Type “internet of things => skynet” into the right pane’s text box, and hit return/enter.

- Click Export (ensuring the tickbox is still selected on the left next to your new item).

- The instruction will be made into code, and shown to you. Something like this …

- Click ‘Apply to selected’ after the code has appeared.

- Click the ‘x’ to close the settings window.

- Click on the Word Replace II icon and ensure it’s enabled (the term enabled will be green).

- Search for “Internet of Things” and see if it works. (If it doesn’t, I’d blame Skynet.) Also, checking the “Internet of Things” Wikipedia page becomes amusing.

- PS If it is working, this post clearly won’t make sense anymore!

CFP: “Infancy Online”–Special Issue of Social Media + Society

Here’s the Call for Papers (well, call for Abstracts, initially) for a special issue of Social Media + Society I’m editing with Bjorn Nansen:

Dear colleagues,

Special Issue of Social Media + Society

http://www.sagepub.com/journals/Journal202332Infancy Online

Eds Tama Leaver (Curtin University) and Bjorn Nansen (University of Melbourne)

From the sharing of ultrasound photos on social media onward, the capturing and communicating of babies’ lives online is an increasingly ordinary and common part of everyday digitally mediated life. Online affordances can facilitate the instantaneous sharing and joys of a first smile, first steps and first word spoken to globally distributed networks of family, friends and publics. Equally, from pregnancy tracking apps to baby cameras hidden inside cuddly toys, infants are also subject to an unprecedented intensification of surveillance practices. Reflecting both of these contexts, there is a growing set of questions about the presence, participation and politics of infants in online networks. This special issue seeks to explore these questions in terms of the online spaces in which infants are present; the forms of online participation enabled for and curated on behalf of infants, and the range of political implications raised by infants’ digital data and its traces, for both their present and future lives. Ideally papers will focus on the impact of digital technologies and networked culture on pre-birth, birth and the early years of life, along with related changes and challenges to parenthood and similar domains.Possible areas of focus include, but are by no means limited to:

• Social media and infant presence and profiles

• Cultural and national specificities of infant media use and presence

• Digital media in the everyday lives of young children

• The app economy, and capture of infant attention

• “Mommy blogs,” and online curation

• Identity and impression management

• Ethics, persistence and the right to be forgotten

• Geographies of infant media use

• Infant interfaces and hardware

• Cultural responses to parenting, “oversharing”, privacy and surveillance

• Erasure of maternal bodies in digitising infancy

• Apps and services targeting infants as a consumer marketAbstracts of 300 words should be submitted to both Tama Leaver t.leaver@curtin.edu.au and Bjorn Nansen nansenb@unimelb.edu.au by Friday, 1 April. Where appropriate, please nominate an author for correspondence.

On the basis of these short abstracts, invitations to submit full papers (of no more than 8000 words) will then be sent out by 15 April 2016. Full papers will be due by 1 July 2016, and will undergo the usual Social Media + Society review procedure. Please note that an invitation to submit a full paper for review does not guarantee paper acceptance.

Instagrammatics: Analysing Visual Social Media

At this week’s fantastically engaging CCI Digital Methods Summer School held at Swinburne University in Melbourne, Tim Highfield and I presented a workshop about analysing visual social media, focusing on Instagram data collection and anaylsis. It was based, in part, on our recent First Monday paper, but also looked beyond that at ways of surfacing research questions and approaches. We were pleased with the interest in the workshop, and really positive responses to it, so we’ve shared the slides here:

There will be more on Instagram from us later this year, but if you’re working on Instagram I’d love to hear what you’re doing; either leave a comment here or ping me an email if you want to get in touch.

2014 & Press Comments…

In reflecting on the year and my quite sporadic blogging (and that’s being generous), it occurred to me that this is in large part because of the amount of time and energy that goes into talking with journalists in the last few years. In 2014 I provided commentary for 31 media stories: 7 newspaper or online stories; 4 TV interviews; and 18 radio interviews. I also wrote a couple of Conversation pieces, and a story for Antenna. This is definitely my preferred ratio: the more radio the better, as it’s almost always live and I feel a lot more in control of the way what I say is actually reported! While is seems a bit boring and self-serving to continually report here when I’ve provided press comments (and something better suited to Twitter), I’ve nevertheless added a media section above so that my public comments are at least available in a central place beyond my CV.

In reflecting on the year and my quite sporadic blogging (and that’s being generous), it occurred to me that this is in large part because of the amount of time and energy that goes into talking with journalists in the last few years. In 2014 I provided commentary for 31 media stories: 7 newspaper or online stories; 4 TV interviews; and 18 radio interviews. I also wrote a couple of Conversation pieces, and a story for Antenna. This is definitely my preferred ratio: the more radio the better, as it’s almost always live and I feel a lot more in control of the way what I say is actually reported! While is seems a bit boring and self-serving to continually report here when I’ve provided press comments (and something better suited to Twitter), I’ve nevertheless added a media section above so that my public comments are at least available in a central place beyond my CV.

My 2014 output was actually down a bit on 2013, when I was interviewed for 38 media stories (19 were print or online; 15 radio interviews; and 4 TV spots). In 2014 I was probably a little pickier about which stories I spoke on, which was influenced both by the rougher media experiences in 2013 as well as me doing a more strategic job of marking out times to focus on my academic writing only. As 2015 kicks off, I’m still going to try and be available to talk about online communication with the press, as I still firmly believe it’s important for academics to try and be public facing and engage with public debate. I’m sure I’ll tweet the better stories, but I’ll also try and keep the media section more or less up to date.

[Photo by reynermedia CC BY]

Is Facebook finally taking anonymity seriously?

By Tama Leaver, Curtin University and Emily van der Nagel, Swinburne University of Technology

Having some form of anonymity online offers many people a kind of freedom. Whether it’s used for exposing corruption or just experimenting socially online it provides a way for the content (but not its author) to be seen.

But this freedom can also easily be abused by those who use anonymity to troll, abuse or harass others, which is why Facebook has previously been opposed to “anonymity on the internet”.

So in announcing that it will allow users to log in to apps anonymously, is Facebook is taking anonymity seriously?

Real identities on Facebook

CEO Mark Zuckerberg has been committed to Facebook as a site for users to have a single real identity since its beginning a decade ago as a platform to connect college students. Today, Facebook’s core business is still about connecting people with those they already know.

But there have been concerns about what personal information is revealed when people use any third-party apps on Facebook.

So this latest announcement aims to address any reluctance some users may have to sign in to third-party apps. Users will soon be able to log in to them without revealing any of their wealth of personal information.

That does not mean they will be anonymous to Facebook – the social media site will still track user activity.

It might seem like the beginning of a shift away from singular, fixed identities, but tweaking privacy settings hardly indicates that Facebook is embracing anonymity. It’s a long way from changing how third-party apps are approached to changing Facebook’s entire real-name culture.

Facebook still insists that “users provide their real names and information”, which it describes as an ongoing “commitment” users make to the platform.

Changing the Facebook experience?

Having the option to log in to third-party apps anonymously does not necessarily mean Facebook users will actually use it. Effective use of Facebook’s privacy settings depends on user knowledge and motivation, and not all users opt in.

A recent Pew Research Center report reveals that the most common strategy people use to be less visible online is to clear their cookies and browser history.

Only 14% of those interviewed said they had used a service to browse the internet anonymously. So, for most Facebook users, their experience won’t change.

Facebook login on other apps and websites

Facebook offers users the ability to use their authenticated Facebook identity to log in to third-party web services and mobile apps. At its simplest and most appealing level, this alleviates the need for users to fill in all their details when signing up for a new app. Instead they can just click the “Log in with Facebook” button.

For online corporations whose businesses depend on building detailed user profiles to attract advertisers, authentication is a real boon. It means they know exactly what apps people are using and when they log in to them.

Automated data flows can often push information back into the authenticating service (such as the music someone is playing on Spotify turning up in their Facebook newsfeed).

While having one account to log in to a range of apps and services is certainly handy, this convenience means it’s almost impossible to tell what information is being shared.

Is Facebook just sharing your email address and full name, or is it providing your date of birth, most recent location, hometown, a full list of friends and so forth? Understandably, this again raises privacy concerns for many people.

How anonymous login works

To address these concerns, Facebook is testing anonymous login as well as a more granular approach to authentication. (It’s worth noting, neither of these changes have been made available to users yet.)

Given the long history of privacy missteps by Facebook, the new login appears to be a step forward. Users will be told what information an app is requesting, and have the option of selectively deciding which of those items Facebook should actually provide.

Facebook will also ask users whether they want to allow the app to post information to Facebook on their behalf. Significantly, this now places the onus on users to manage the way Facebook shares their information on their behalf.

In describing anonymous login, Facebook explains that:

Sometimes people want to try out apps, but they’re not ready to share any information about themselves.

It’s certainly useful to try out apps without having to fill in and establish a full profile, but very few apps can actually operate without some sort of persistent user identity.

The implication is once a user has tested an app, to use its full functionality they’ll have to set up a profile, probably by allowing Facebook to share some of their data with the app or service.

Taking on the competition

The value of identity and anonymity are both central to the current social media war to gain user attention and loyalty.

Facebook’s anonymous login might cynically be seen as an attempt to court users who have flocked to Snapchat, an app which has anonymity built into its design from the outset.

Snapchat’s creators famously turned down a US$3 billion buyout bid from Facebook. Last week it also revealed part of its competitive plan, an updated version of Snapchat that offers seamless real-time video and text chat.

By default, these conversations disappear as soon as they’ve happened, but users can select important items to hold on to.

Whether competing with Snapchat, or any number of other social media services, Facebook will have to continue to consider the way identity and anonymity are valued by users. At the moment its flirting with anonymity is tokenistic at best.

![]()

Tama Leaver receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC).

Emily van der Nagel does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

A reminder about academics giving comments to journalists (and sex, and the web, too!)

My Sunday began with a twinge of disappointment as I found out that an interview I’d given to a local reporter had been used to give credence to an awfully sensationalist moral panic piece about young people, sexting, and anonymous messaging apps (mainly Snapchat and Facebook’s new Poke). While The Sunday Times isn’t exactly a bastion of investigative journalism, I was nevertheless disappointed since I’d tried to provide a bit of context for these apps, emphasising that in the vast majority of cases the material being sent was harmless, but that when more intimate material was shared, the most important dynamic was trust between the people communicating, not the nitty gritty technical details of the app itself (if someone really wants to find a way around deleting online material, they will). I know academics should always be wary of journalists reporting on sensationalist topics, and to be fair I’m not actually misquoted, just used to add support to an otherwise pretty vacuous piece, but it nevertheless smarts to be associated with a story using the headline ‘Teen Sext Trap’ in giant letters.

My first instinct was to be very annoyed with the journalist, Katie Robertson, who I’ve provided comments for in the past. However, after searching the web, I was swiftly reminded that journalists are but one (small) cog in the machinery of sensationalism. This became evident when I found several versions of the same story, in different locations all owned by Murdoch’s NewsCorp (as is the Sunday Times).

Take a look, for example, at the Sunday Times version:

(You can see article on the Sunday Times front page in all its glory.) An online version under the headline ‘Teenagers embrace new secret sexting craze on smartphones’, with the same text from the Sunday Times version, also appeared on the Perth Now website, and The Australian website.

However, in contrast, another version appears in print on the other side of the country in the Tasmanian Sunday:

The Tasmanian Sunday version, written by the same reporter, released on the same day, is far more balanced and does justice to what I’d mentioned in her interview. I suspect – and haven’t yet asked – that this second version is closest to the article originally written, and that the Sunday Times (and online) version has seen a lot more input from editors seeking to increase sales. This is always the case – that the editors overrule the journalists – but often this input is, initially, invisible. Now I’ve been reminded, I’ll do a better job of remembering that even when you feel a decent rapport with a journalist, they often won’t have control of the words that are released under their name. That said, I do think it’s very important that academics engage with the press since it’s often in that arena where the public come across important information. For me, it just means being a little more wary (and possibly sticking to radio whenever possible).

In terms of this story, it’s the last few lines of the Tasmanian Sunday version that I think matter the most, and since they’re my words, I thought it would be worth posting them here. With regard to Snapchat, Facebook’s Poke or any other self-deleting messaging app that comes along:

There will always be safeguards in place, but you can almost always get around them if you try. Any form of communication online has to involve a level of trust. In 99.9 per cent of cases, though, the fact that it is deleted will mean it is deleted. … But parents should always have a chat with their kids about anything shared online as it has the potential to last forever.