Home » web2.0 (Page 4)

Category Archives: web2.0

Wikipedia: What’s in it for Teachers?

[This article was originally published in Screen Education, 53, Autumn 2009, pp. 38-42. It is reproduced here with permission.]

Love it or hate it, everyone has heard of the Wikipedia. Explore most topical subjects on popular search engines like Google and the relevant Wikipedia entry will almost always be in the first few items returned. And far from a flash in the pan, on January 15 2010, the Wikipedia celebrated its ninth birthday, now encompassing more than 10 million articles spanning over 250 different languages. Yet, for teachers and academics the Wikipedia can be a constant source of concern as students increasingly start (and, in the worst cases, end) research on a new topic with a quick peruse of the Wikipedia entry. The biggest concern comes from the core premise of the Wikipedia: it’s an online encyclopaedia that can, literally, be edited by anyone. Yet for all of the fashionable talk of crowdsourcing, collective intelligence and the wisdom of the crowds, most educators prefer their students to be using sources which have more authority and reputation behind them. But is that concern warranted, and given that the Wikipedia is slowly finding a home in classrooms across Australia, what do teachers really need to know about the Wikipedia?

How the Wikipedia Works

From the outset, it is useful to remember that the Wikipedia is just one example, albeit the most well-known, of a website which uses wiki software. A wiki, by definition, is type of software which powers websites and allows anyone to edit and contribute. The wiki software that provides the architecture for the Wikipedia is called MediaWiki and is freely downloadable and reusable (see MediaWiki.org) although that requires server-space and a reasonable level of technical skill. If you’re interested in trying out a wiki, or using a free wiki in teaching, pbworks.com is a good place to start, providing basic wiki functionality for free (and more comprehensive tools for teaching for a fee).

The Wikipedia itself was launched in January 2001 by Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger, taking its name from the combination of the words wiki and encyclopaedia. The aim of the Wikipedia is fairly simple: to produce and continually improve an online encyclopaedia that is free for anyone to use and, most importantly, can be edited by anyone. After a slow start, the Wikipedia today features over 3.3 million articles in English, with articles in hundreds of languages and it is one of the most popular reference works in the world.

Since the range of articles in the Wikipedia is largely dependant on the interest of contributors (referred to as Wikipedians), the coverage is often uneven; popular culture, recent historical events, and technical issues tend to be very well represented while less topical or more geographically-specific material can be sparse. For example, the Wikipedia entry for the current run of the popular BBC series Top Gear is more than five times longer and has more than three times the references compared to the article for Australian novelist Tim Winton. More to the point, since Wikipedia entries tend to grow over time though the contributions of many editors, newer entries are often less reliable, while those which have been edited and critiqued by a range of Wikipedians tend to be more reliable. The question of reliability, though, given the huge range of people who might contribute to, or ostensibly damage, an article, remains the most divisive issue for lovers and haters of the Wikipedia.

The Reliability Question

While the idea that anyone can edit the Wikipedia causes many people to scoff at the idea of it having any credibility whatsoever, this presumption has actually been tested far less often than it should be. In 2004, Alex Halavais, an assistant professor at Quinnipiac University, looked in to the question of the Wikipedia’s credibility and was surprised to find almost no research on the issue whatsoever. After an online discussion, he decided to test out the speed at which the numerous editors of the Wikipedia would actually be able to fix mistakes. Halavais created a pseudonym and a Wikipedia profile as ‘Dr al-Halawi’ and made 13 deliberate errors, some obvious and some obscure. He predicted that within two weeks many of these errors would remain undetected. However, within several hours, all of the deliberate errors were identified by other Wikipedians and those errors were removed.

Writing in his blog (alex.halavais.net), Halavais noted that he was genuinely impressed by the speed and effectiveness with which the Wikipedia entries were corrected. While he conceded that his experiment didn’t ‘prove’ that the Wikipedia was reliable for everything, he did highlight the time and effort many people put into the Wikipedia, and that editors often also see themselves as guardians of particular articles, even obscure ones.

It’s worth explaining that one of the functions all registered Wikipedia users have access to is something called a Watchlist. Whenever an article on a user’s watchlist is edited by someone else, the watchlist user is sent a message and, upon notification, many Wikipedians will immediately examine the new material. In the cases of obvious vandalism or error, these errors are often ‘rolled back’ within minutes (that is, the Wikipedia entry is returned to the previous version before the errors were made). For more popular articles, Wikipedians with watchlists can be extremely effective, but even the more obscure articles often end up with one or two watchers, ensuring that obvious errors tend not to last that long. There are, of course, exceptions to that rule, especially for entries which not of ongoing interest to the Wikipedians who originally created them.

In December 2005, a more substantial and widely reported study was undertaken by the leading scientific journal Nature. Articles from the Wikipedia and the Encyclopaedia Britannica on the same topics were collected and then sent for blind-review to experts on those topics; the experts were not told which articles were from which source. While there were a few substantial errors in either, on average Wikipedia entries tended to have roughly 4 inaccuracies, while the same entries from the Encyclopaedia Britannica had approximately 3 errors. The results suggested that neither Wikipedia nor Britannica was flawless, but that the reliability gap between the two was fairly small. Indeed, given the seemingly haphazard manner in which Wikipedia entries and created and refined, the Nature study has been hailed by many commentators as evidence of impressive collective intelligence of Wikipedians, and of Wikipedia’s success and credibility.

The Nature examination also highlighted the biggest difference between the two sources: while errors in Britannica would have to wait until the next hardcopy edition was created, Wikipedia entries could be fixed instantly. Indeed, it is the speed at which the Wikipedia entries can appear and develop which is often mentioned as its greatest strength. And while neither the experiments of Halavais or Nature suggest Wikipedia is perfect, it appears almost as reliable as its well-respected hardcopy competitors.

The Neutrality Question

One of the core principles of the Wikipedia is that articles should be factual and be written using a Neutral Point of View (or NPOV). This policy ensures, for example, that any claims made without the appropriate sources or references can be easily identified and removed. However, given the breadth of material covered and the number of editors, the ideal of objectivity or neutrality is a difficult one to maintain. The entry on global warming, for example, has a long history of changes and arguments between editors which has, at times, led to certain Wikipedians being blocked from editing the entry. Similarly, while the Wikipedia could easily be used as a promotional tool or for self-aggrandisement, autobiography and obvious conflicts of interest are highly discouraged. The only exception to these guidelines is the right to correct obvious factual errors.

In 2007 the Howard government was wrapped up in its own scandal when a new website launched (unaffiliated with the Wikipedia) called the WikiScanner. The Wikiscanner highlights how many changes to the Wikipedia come from any particular internet address. Journalists and others quickly pounced on this tool and found that staff in Prime Minster Howard’s department had been actively editing unfavourable entries, including those about the 2001 Children Overboard Affair and the biography of Peter Costello. The Wikiscanner also revealed thousands of changes originating from computers in Australia’s Defence Department, although this practice was quickly clamped down on, with official Defence Department rules now preventing changes being made (while at work, at least). While many of the changes were either predictable (like inserting the word allegedly into reports about the Children Overboard Affair) or inconsequential, the fact that the Howard government or the Defence Department would bother to edit the Wikipedia is a clear indication of the wide impact the Wikipedia has had across Australia and the wider world.

In 2005 one of the most biggest controversies to hit the Wikipedia erupted when well-respected US journalist and political figure John Seigenthaler had it brought to his attention that the Wikipedia entry about him falsely accused Seigenthaler of being linked to the assassinations of John F Kennedy and Robert Kennedy. At issue was not just the false information, which was removed fairly quickly after the hoax entry was exposed, but the fact that the erroneous entry had last for 4 months before someone noticed the problem. Seigenthaler’s reputation and the obviously false accusations were something of a blow to the Wikipedia, and the issue of Wikipedia’s reliability again became a hot topic in the media. In response to the Seigenthaler incident, the Wikipedia introduced new safeguards which meant some entries were protected from editing, while others could only be edited by trusted Wikipedians who had proven their reliability with a history of useful contributions. This is illustrated, for example, in that immediately before and during the inauguration of Barack Obama, the entries both for Obama and George W Bush were in ‘semi-protected’ mode. This mode means only Wikipedians who’ve made non-controversial edits to more than 10 articles over a period of time and have thus earned a level of trust, can edit these biographies. The biographical entries for many current and recent political figures are in semi-protected mode, as this prevents anonymous users, first-time users and automated scripts from altering and vandalising content. While these restrictions alter the ‘anyone can edit’ philosophy behind the Wikipedia, the changes do offer a higher level of credibility and reliability, especially surrounding hot topics and public figures, trying to maintain the ideal of neutrality.

Using Wikipedia in the Classroom

So with the caveats about credibility and neutrality in mind, what place can the Wikipedia have in the classroom? More to the point, given that many of our students are using it whether endorsed by their teachers or not, how can we try and ensure that, at the very least, students approach the Wikipedia with a critical eye?

In trying to understand the Wikipedia, the most obvious approach is to try and design a project in which students edit or create a Wikipedia page. Such a project ensures that students get first-hand experience of everything from logging in, to creating content and then working with whatever alterations or contributions come from the broader Wikipedian community. The success or failure of such a project will often hinge on carefully considering the topic to create or explore. For example, editing the biography of John Howard might be interesting, but students are likely to come up against a fairly detailed existing entry and there will probably be quite a few vested Wikipedians watching over this entry; this, in turn, might see contributions from the classroom quickly overturned. However, one of the least well-documented areas of in the Wikipedia is often local history. So a project, for example, which involved students researching their local suburb’s history, or the history of a significant community landmark or event, is far more likely to be of value both as a project and to the Wikipedia itself. Wikipedia’s policy of ensuring material is referenced would require students to do decent research, while creating a local historical entry could add both to their understanding of local history and their understanding of the Wikipedia. Wikipedians themselves suggest that one of the best ways for teachers to introduce the Wikipedia is for the whole class to use a single username and password. This allows teachers to moderate and, if needs be, to remove student contributions. If you’re considering trying out using the Wikipedia as a classroom activity, it’s worth taking a look at the Wikipedia’s guide for teachers, at: http://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Schools/Teachers%27_Guide.

Another possibility, rather than creating entries, is to study the Wikipedia as both a cultural and social entity. Making such a study of real value are some of the greatest assets of the Wikipedia, which are not the entries themselves, but the editorial histories which are linked to each and every Wikipedia entry. Every article has an associated Discussion and History page (accessed via tabs at the top of each entry). The Discussion page (often just called Talk) is the place where Wikipedians can propose, discuss, argue and critique changes and suggested changes to articles. These pages can sometimes be banal, but often they reveal a great deal about the way people think about particular topics; these discussions can also serve as a compass in measuring what the debates are surrounding certain topics or subjects. Similarly, the History page shows the detail of each and every change made to an entry since it was first created, including any instances where the entry was ‘rolled back’ to a previous version after a contribution that was not judged worthy by other users. Again, this depth of editorial knowledge can reveal a great deal about how certain topics are explored and the way entries have evolved. Beyond individual entries and their histories, studying the Wikipedia as an entity is made far more interesting by examining the Wikimedia Foundation, who run the Wikipedia; in a community of peers, they the ones who still hold unrivalled power in over the online encyclopaedia. Jimmy Wales, the remaining founder of the Wikipedia, is also a colourful and at times controversial character in his own right. It is worth noting that as part of the Global Village elective in this year’s English syllabus for the NSW HSC the Wikipedia itself is suggested as an object of study and amongst the suggested pages are those which discuss the Wikimedia Foundation, not just individual entries.

The final suggested classroom activity is for students to undertake a detailed analysis of an individual Wikipedia entry, often one which is on a currently controversial or topical issue. If, as the Nature investigation revealed, most Wikipedia entries have some errors, what might those errors be? If students were starting from scratch on a particular topic, how would they approach their research? Is this approach reflected in the Wikipedia entry, or do their plans already reveal deficiencies in the information available? What impact does the Wikipedia’s neutrality policy have on what information is and isn’t part of that particular entry? And how accurately, or meaningfully, does the Wikipedia entry reflect the history or impact of that subject today? In comparing the Wikipedia entries with other sources, not only are students likely to discover the strengths and weaknesses of the Wikipedia, but they’re also likely to develop broader insight into the way information is presented in different sources, both online and in more traditional forms. This critical literacy may, in fact, be of far more value than any single investigation of the Wikipedia whatsoever as it may help teach students one of the most important lessons: that all sources should be approached critically, regardless of their supposed origins. Errors are always possible, and if an investigation into the Wikipedia can highlight the subjective nature of all information, that insight will serve students far beyond the immediate project they’re undertaking.

The appropriateness of the Wikipedia as a classroom tool or project will always depend on the specificities of that teaching environment, but given the widespread impact of the Wikipedia, it seems better to study it and highlight its strengths and weaknesses rather than ignore it altogether. Another way to get a firmer grip on the Wikipedia is to seek out a the recently published How Wikipedia Works: And How You Can Be a Part of It by Phoebe Ayers, Charles Matthews, and Ben Yates (No Starch Press, 2008) which was written by three long-time Wikipedians and gives a wealth of insight into the inner workings of the Wikipedia, as well as best practice for new users and educators seeking to use the Wikipedia for the first time. However, the single most important thing to remind students is that despite being online, the Wikipedia aspires to being an excellent encyclopaedia; simply citing an encyclopaedia without further research has never led to good marks and that’s unlikely to change any time soon, be it an online encyclopaedia or otherwise. Every Wikipedia entry cites its sources, following these is where real research can often begin.

Digital Culture Links: August 24th 2010

Links for August 17th 2010 through August 24th 2010:

- Social Steganography: Learning to Hide in Plain Sight [DMLcentral] – danah boyd on social steganography: “… hiding information in plain sight, creating a message that can be read in one way by those who aren’t in the know and read differently by those who are. […] communicating to different audiences simultaneously, relying on specific cultural awareness to provide the right interpretive lens. […] Social steganography is one privacy tactic teens take when engaging in semi-public forums like Facebook. While adults have worked diligently to exclude people through privacy settings, many teenagers have been unable to exclude certain classes of adults – namely their parents – for quite some time. For this reason, they’ve had to develop new techniques to speak to their friends fully aware that their parents are overhearing. Social steganography is one of the most common techniques that teens employ. They do this because they care about privacy, they care about misinterpretation, they care about segmented communications strategies.”

- The Mother Lode: Welcome to the iMac Touch [Patently Apple] – A look at a patent for the future iMacs which shows the entire desktop computer will soon be enable as a giant touch-screen device thanks to the technology developed creating the iPad and Apple’s new iOS touch-based operating system.

- Sweden Rescinds Warrant for WikiLeaks Founder [NYTimes.com] – Julian Assange, the Wikileaks founder, was, for a brief time, up on rape and molestation chages in Sweden before the charges were rescinded just as quickly as they’d appealed. In a context where the Pentagon and others have said they’ve the resources to close Wikileaks and prosecute Assange, this whole debacle seems entirely suspicious.

- Share Bookmarklet [Twitter] – The official Twitter Bookmarklet, streamlining the sharing of any site or page on Twitter via a bookmarked link in your browser.

- Our Natalie raking in $100,000 a year from YouTube [The Age] – Australian YouTube sensation Natalie Tran is reported making more than $100,000 Australian dollars from the advertising on her clips, Community Channel.

- Facebook scam lures users craving ‘Dislike’ button [SMH] – This scam works because so many people want a DISLIKE button on Facebook! “Computer security firm Sophos has warned that scammers are duping Facebook users with a bogus “Dislike” button that slips malicious software onto machines. There is no “Dislike” version of the “Like” icon that members of the world’s top social networking website use to endorse online comments, stories, pictures or other content shared with friends. Hackers are enticing Facebook users to install an application pitched as a “Dislike” button that jokingly notifies contacts at the social networking service “now I can dislike all of your dumb posts.” Once granted permission to access a Facebook user’s profile, the application pumps out spam from the account and spreads itself by inviting the person’s friends to get the button, according to Sophos.”

Initial Thoughts on Facebook Places

Earlier today Facebook announced the release of their long-rumoured geographic tagging tool, Facebook Places. In a nutshell, Places will allow smartphone-wielding users to ‘check in’ at whatever notable location they happen to be, and share that information with friends on Facebook (who, as per your privacy settings, will either be a very small group or all 500 million+ Facebook users). The history of whose checked in where will become part of the Facebook record for that place, and thus any tagged comments people make in or about those places will become part of, effectively, place history.

Earlier today Facebook announced the release of their long-rumoured geographic tagging tool, Facebook Places. In a nutshell, Places will allow smartphone-wielding users to ‘check in’ at whatever notable location they happen to be, and share that information with friends on Facebook (who, as per your privacy settings, will either be a very small group or all 500 million+ Facebook users). The history of whose checked in where will become part of the Facebook record for that place, and thus any tagged comments people make in or about those places will become part of, effectively, place history.

While similar check-in services like Foursquare already exist, the huge number of Facebook users means that this has the potential to bring place-based social sharing even further into the mainstream. Indeed, at the Places launch, Facebook has already announced partnerships with many place-based services, including Foursquare, Gowalla and Yelp; check-ins on those services can also become check-ins on Facebook Places in the near future.

Facebook’s unique selling point, of course, will be capitalising on the existing social networks people have established. Facebook Places will actually allow people to tag friends, much in the way you can currently tag friends in photos. One iPhone user will be able to tag the all of their relevant Facebook friends as they check-in somewhere. While this is certainly very social, it’s also a huge boon to business and advertisers, and raises a whole new raft of privacy concerns.

For businesses, especially small businesses, Facebook Places has enormous potential. Localised reviews and ratings have been popping up all over the web for years, but the reach of Facebook, and the ease of access, will make social commentary of restaurants, clubs and other businesses easily aggregateable and accessible. Facebook have already indicated that Facebook business pages will be able to integrate the related Facebook Place information. While Facebook themselves aren’t immediately releasing game-based tools with Facebook Places, canny businesses will surely take up this data to reward/encourage customers – as the have with Foursquare – ‘10 Facebook Place check-ins and get a free muffin’ will be with us soon. Of course, an inevitable legal battle is also just around the corner: which will be the first business to sue a Facebook user for a negative comment about that place? The divide between expressing an opinion, and effectively reviewing a location, will certainly blur even further.

With all of this new information sharing come massive privacy questions, and questions which in typically Facebook style they’ve deferred to an opt-out mentality: users will be able to chose, using one of those elusive privacy settings, to either disable other people checking them into places, or they can remove check-ins manually, similar to the way folks can un-tag themselves in unflattering photos. By default, though, it seems everything will be turned on, and users will have to actively seek to disable Facebook Places if they don’t wish Facebook to build a history of where you’ve been. It’s worth noting that the New York Times, The Guardian and Mashable all have articles up citing privacy concerns about Facebook Places, before the service is even a day old. It’ll be interesting to see what problems Facebook encounters with Places, but they’ll no doubt do as they always have: turn it on, let everyone try it out, then slowly deal with whatever complaints and protests arise, knowing full well that 99% of users will never leave Facebook for fear of giving up vital social capital.

Initially, Facebook Places is only available in the US (and thus the official Facebook Places page will show you nothing in Australia today) but it’s sure to land here in the near future. Oh, and no use trying to set you privacy in advance: I’ve checked, and I can’t find a way to pre-emptively disable other people checking me in; I guess I’ll have to remember to do that once the service is activated down under. Update: It’s now possible to opt-out and disable other people checking you in, no matter what country you’re in. If you want to disable other people’s ability to add you to their check-in entirely, then follow these instructions from Valleywag.

Update: While it’s pretty clear that Facebook Places is yet another tool to entice advertisers to Facebook, often seen in direct competition with Google, in a move that really highlights Facebook’s desire to challenge Google, the maps used by Facebook Places will be exclusively powered by Microsoft’s Bing Maps.

Update 2: Facebook Places went live in Australia on 30 September, and it took only hours for the first privacy concerns to arise.

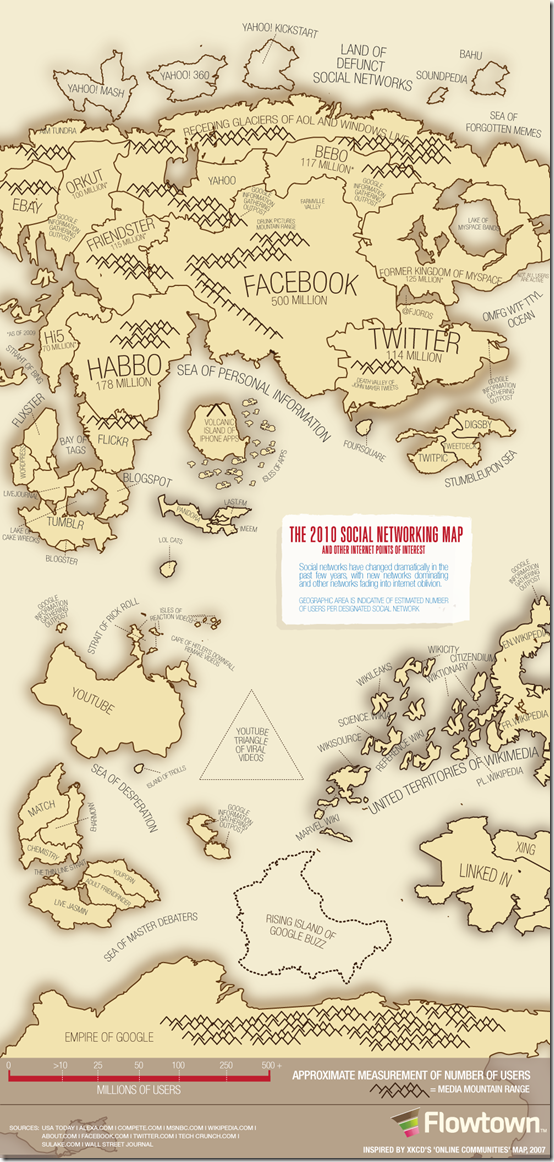

2010 Social Networking Map

A great 2010 update from Flowtown’s Ethan Bloch of the (in)famous XKCD Map of Online Communities.

Update: Or you might prefer your map horizontally …

Wendy NOT 4 Senate

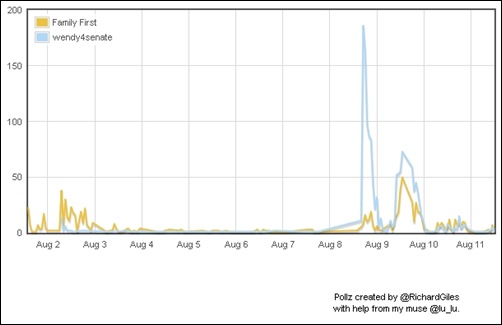

So, in an electioneering Australia political landscape most notable for not being notable, it’s the bigots and racists that seem to stand out, and that seems to be the home territory for Family First senatorial wannabe Wendy Franics who, yesterday on Twitter suggested allowing gay couples to be parents was tantamount to child abuse. The rapid, wide-spread dismay and denouncement of her tweets seems to have shaken Francis, who deleted her tweets, only to discover that people take screenshots of stupid stuff other people say online. Indeed, responses to Francis’ bigotry have become a hot-topic on the #ausvotes hashtag, proving that in an election it’s certainly not true that all publicity is good publicity! In a follow-up interview, Francis has been unable to justify deleting her offensive tweets, but has rather gone on to dig an even deeper hole for herself. Meanwhile, the inevitable parody Fake Wendy Francis tweet account – Wendy2TheSenate – is already making the most of Family First’s predicament (it’s a lot more fun to read than her real Twitter account). It’s also interesting to note how effectively Twitter Lists can be used to protest about someone’s bigotry (screen capture; oh, and that picture/link contains some naughty words!).

As this graph shows, within the #ausvotes tweets on Twitter,Francis’ gaffe certainly got attention, more attention even than her party en masse, but that’s not the attention most politicians are after on the way to an election:

[Graph generated by Pollz.]

Digital Culture Links: August 4th 2010

Links for August 4th 2010 (definitely not endorsed by any version of Andrew Bolt):

- Andrew Bolt discovers Twitter fake. Is cross. [mUmBRELLA] – News Ltd columnist Andrew Bolt has, it would appear, had something of a sense of humour failure over his fake Twitter persona. This morning, Bolt wrote in his Herald Sun blog: “It shouldn’t need saying, but I do not have a Twitter account and the fake one seems to be the work of people whose employer will be very embarrassed to find its staff once more engaging in deceitful slurs. A little warning there. A tearful sorry afterwards will be both too late and insincere, especially from people with their record of sliming.” The fake Andrew Bolt, who has about 5000 followers, does give certain subtle clues on Twitter that he ain’t the real deal. Such as his bio: “Journalist. Blogger. Broadcaster. Climate scientist. Great in bed. This is the Twitter of Andrew Bolt. Follow me you barbarians.” Or messages such as: “Julia Gillard should put together a comittee of common folk to see if they can change the laws of physics. I suspect they can.””

- Andrew Bolt is not happy about @andrewbolt [Peter Black’s Freedom to Differ] – Peter Black looks at the legal side of (fake) Andrew Bolt on Twitter: “…it seems to me that Bolt would at least have an arguable case, that one or more of the tweets constituted a defamatory imputation. Moreoever, they were referrable to Bolt and published. It is also worth noting that cartoons, caricatures, jokes or satire may be defamatory depending upon the context of the publication (see Entienne v Festival City Broadcasters (2001) 79 SASR 19). How a jury would construe these statements, given they take place in the context of a fake Twitter account, is hard to predict. Nonetheless, I do believe that a judge would find that the material is capable of defaming Bolt and that it would then be up to a jury to decide whether the material actually defamed Bolt. So while I think it is highly unlikely Bolt would actually sue for defamation, it is worth remembering that even fake Twitter accounts, while intended for the purpose of satire and humour, may well have legal consequences.”

- Twitter List @andrew__bolt/AndrewBolt – A list of more than 30 ‘Andrew Bolt’ (fake) accounts on Twitter, the majority of which have appeared in the last 24hrs since Andrew Bolt (the man) complained about @andrewbolt (the most popular fake, on twitter).

- SRSLY? SMS Celebrates Its 25th Birthday [The Next Web] – “According to a press release from Sherri Wells, ‘one of the leading SMS messaging experts in the world’, SMS is celebrating 25 years of existence today, making its way from a R&D lab at Vodafone to become a technology that is now present on every single mobile phone currently in existence. Although SMS was developed twenty-five years ago in a collaboration between France and Germany, the first text message was actually sent seven years later on December 3rd, 1992, reading “Happy Christmas”. Since then SMS evolved through various stages, starting as a free service where teens helped popularise the service, before carriers then charged for the service, causing a decline of up to 40% in the process. Back in 2000, the average monthly texts sent per user was a paltry 35, today it’s as high as 357 with 1.5 trillion messages sent annually in the US.”

- Bill Cosby dead rumours dismissed on Twitter [WA Today] – Tweets of my death have been greatly exaggerated! “Television star Bill Cosby has been forced to reassure fans he’s still alive and well after news of his ‘death’ became a top trending topic on Twitter. ‘Bill Cosby died’ remains the fifth highest trending topic on the micro-blogging site this morning. “Emotional friends have called about this misinformation,” the Cosby Show star tweeted in response to the announcement. “To the people behind the foolishness, I’m not sure you see how upsetting this is. “Again, I’m rebuttaling rumours about my demise (sic).” This is the second time this year that Cosby has been pronounced dead by social media.”

- Old Spice Voicemail Generator – Make your own voicemail or answering machine message made up of audio samples from the Old Spice guy’s recent replies. This voicemail is now diamonds! (By Chriswastaken, Area, and Nelson Abalos Jr | Thanks to Reddit)

- YouTube Star to Put His Life in Your Hands for a Year [Mashable] – “Heyo all you megalomaniacs out there — may we introduce yet another way to get your jollies this year: Dan 3.0. Starting today, 20-year-old YouTube sensation Dan Brown is launching a new web show/social experiment in which he will turn control of his life over to you, the viewers, for an entire year. Brown […] is one of those rare dudes whose only gig is video blogging. […] When asked how he thinks this project will affect his day-to-day life, Brown told us: “Basically I’m going to be living my life, doing what my viewers tell me and documenting it. That’s going to be it. Daily life is going to be affected – I don’t know exactly what it means for relationships with friends and relationships with people I know in real life. I guess we’ll find out when we get there.” So as to prevent any catastrophes, Brown has a few ground rules. Viewers can’t ask him to do things like, say, dump his girlfriend, or to do anything illegal or harmful to others. He has also veto power …”

- Google Android phone shipments increase by 886% [BBC News] – There’s a lot more smartphones out there: “Google Android phone shipments increase by 886% Shipments of Google’s Android mobile operating system have rocketed in the last year, figures suggest. Statistics from research firm Canalys suggest that shipments have increased 886% year-on-year from the second quarter of 2009. Apple showed the second largest growth in the smartphone sector with 61% growth in the same period. Overall, the smartphone sector grew by 64% from the second quarter 2009 to the second quarter 2010, the research says.”