Home » student engagement

Category Archives: student engagement

Doing Cultural Studies 2013 Roundtable: Academic Career Practice

On 3 December 2013 I had the pleasure of participating in the Doing Cultural Studies: Interrogating ‘Practice’ symposium backed by the CSAA and Swinburne University, and very professionally organised and run by the postgraduate trio Jenny Kennedy, Emily van der Nagel and James Meese. The day highlighted some impressive emerging work by postgraduate students and early career researchers in cultural studies, and featured an outstanding Keynote provocation by Katrina Schlunke (video here).

For a taste of the many excellent paper presentations, Jenny Kennedy created a Storify which curates many of the tweets from the day.

My contribution was as part of a panel addressing Academic Career Practice which was addressed more practical questions about balancing research, careers and teaching. The panellists were myself, Esther Milne and Brendan Keogh, with Ramon Lobato chairing. A recording of the panel discussion is below:

National Teaching Award!

At an amazing ceremony and dinner at the National Gallery in Canberra tonight I was surprised, flattered and delighted to receive an Australian Award for University Teaching in the Humanities and Arts. This is a huge honour, and I’m extremely grateful to have my approaches to learning and teaching acknowledged in this manner. That said, I’m incredibly conscious that no one teaches in a vacuum, and in Internet Communications I am but one cog in a very complex and well-maintained machine, so this award is at least as much testimony to all of our team at Curtin University as it is to me.

Most importantly, though, I wanted to publicly thank the students who offered their thoughts and feedback about my teaching. We live in an era where students get asked to fill in an awfully large number of feedback forms, surveys and evaluations, so adding even one more thing to that pile is a big ask. So, THANK YOU to all of my students, current and past, whose kind words led to this award.

I’d also like to think that this award is a reminder that despite the huge media attention being paid to MOOCs and so forth, quality online education has been available and refined over more than a decade, and our Internet Communications program is one such example. I truly hope that as this next generation of online learning matures, close attention will be paid to successful examples already available! Successful learning and teaching is, after all, built on understanding the successes and failures of the past.

CFP: An Education In Facebook?

Along with my colleagues Mike Kent and Clare Lloyd we’re working on an edited collection about the joys, perils and uses of Facebook in higher education (of any sort). Here’s the CFP (call for papers) if you’re interested. Please feel free to distribute this post wide and far if you’d be so kind!

An Education in Facebook?

Higher Education and the World’s Largest Social NetworkEditors: Dr Mike Kent, Dr Tama Leaver and Dr Clare Lloyd, Internet Studies, Curtin University

Abstract Submission Deadline 18 January 2013

Full Chapters Due 31 May 2013

We are soliciting chapter proposals for an edited collection entitled An Education in Facebook? This edited collection will focus on the relationship between Facebook and Higher Education. Facebook first emerged in 2004 as a social network for students studying at universities in the United States. It soon grew beyond North America, and beyond the confines of student networking. Having evolved initially as a student social space the platform continues to play a prominent role in the lives of many students and staff at higher education institutions.

The collection will explore the use of Facebook the higher education environment as both a social space, and also its growing use as part of teaching and learning processes, both formally and informally. From students creating informal social groups around a course of study or particular unit, and dedicated online study groups, to the use of Facebook as a formal venue for teaching, we are seeking chapters that explore these and related areas.

Is there an appropriate place for Facebook in formal higher education? What are the tensions between private and professional spaces online for students and teachers and what are the potential dangers of unintentional overlap? What are appropriate roles and responsibilities for staff, students and institutions in relation to the social network? What are the dangers of moving important aspects of the higher education learning environment to an external company that exploits social interaction for profit? How is the shift to online learning in many institutions complemented or challenged by mobile uses of social networks, including app use on smartphones and tablets? This book will explore these and other topics interrogating the contemporary role of Facebook in Higher Education.

Some suggested topics (which are by no means exhaustive):

- · Facebook and/as/or Learning Management Systems?

- · Facebook as support network (for online and overseas learners, for example)

- · Teacher-led Facebook uses as in/formal learning

- · Student-led Facebook uses as in/formal learning

- · Case studies of Facebook implementation in formal learning

- · Informal versus formal learning online

- · Social networks and the flipped classroom

- · Context collapse

- · Privacy issues in social network use

- · Copyright issues in social network use

- · Mobile learning

- · The Facebook App in education

- · Roles and boundaries in networked learning

- · Facebook as a backchannel (either positive or disruptive)

- · The politics of ‘friending’ in staff and student relations

- · Examples of innovative Facebook integration in higher education

- · Whether Facebook has a place in formal education

- · MOOCs and Facebook

- · Comparative uses of Facebook and other online networks (eg Twitter)

Submission procedure:

Potential authors are invited to submit chapter abstract of no more than 500 words, including a title, 4 to 6 keywords, and a brief bio, by email to both Dr Mike Kent <m.kent@curtin.edu.au> and Dr Tama Leaver <t.leaver@curtin.edu.au> by 18 January 2013. (Please indicate in your proposal if you wish to use any visual material, and how you have or will gain copyright clearance for visual material.) Authors will receive a response by February 15, 2013, with those provisionally accepted due as chapters of no more than 6000 words (including references) by 31 May 2013.

About the editors:

The three editors are from the Department of Internet Studies at Curtin University. Dr Mike Kent’s research focus is on people with disabilities and their use of, and access to, information technology and the Internet. He recently co-authored the monograph Disability and New Media (Routledge, 2011). His other area a research interest is in higher education and particularly online education. Dr Tama Leaver researches online identities, digital media distribution and networked learning. He previously spent several years as a lecturer in Higher Education Development, and is currently also a Research Fellow in Curtin’s Centre for Culture and Technology. His recent book is Artificial Culture: Identity, Technology and Bodies (Routledge, 2012), and he is currently co-authoring a monograph entitled Web Presence: Staying Noticed in a Networked World. Dr Clare Lloyd specialises in mobile communication and mobile media. Her recent publications include the co-authored papers ‘Consuming apps: the Australian woman’s slow appetite for apps’ (2012); and ‘Fun and useful apps: female identity construction and social connectedness using the mobile phone’ apps’ (2012).

Developing a Web Presence During Candidature

I gave a short seminar today on the topic of developing a web presence during candidature. Honours, masters and doctoral students increasingly need to be aware of the tools and conventions that most directly allow them to be part of their scholarly field online. Hopefully this presentation gave some students here at Curtin some beginning ideas. I fear the slides are somewhat less useful without the presenter, but on the off chance they’re useful to anyone, here you go:

As always, comments are most welcome.

State of the Internet (in 4 minutes …)

As I welcome 300 students into Web Communications 101 at Curtin University today (both on-campus and via Open Universities Australia), my mind is already wandering to lectures and finding engaging ways to present the material. With that in mind, there are some nice infographics in this 4 minute video by Jesse Thomas which gives a wrap-up of the ‘State of the Internet’ (a la 2009):

JESS3 / The State of The Internet from Jesse Thomas on Vimeo.

Of course, 2009 internet stats are already getting dated, but the video is very pretty! 🙂

The Creative Commons: An Overview for Educators

[This post was originally published in Screen Education, 50, Winter 2008, pp. 38-42. It is reproduced here with permission. The article was (and is) aimed at media teachers in Australia, but hopefully may be of use more broadly, too.]

As teaching media and, more to the point, teaching media literacies becomes more and more central in both K-12 and tertiary settings, one of the biggest challenges is the gargantuan monolith of copyright. By copyright, I don’t necessarily mean teaching how copyright works – although that certainly isn’t the most straight forward process – but of more difficulty are the roadblocks that copyright laws puts in place. Immediately some canny readers will retort that most Australian schools and universities have access to particular exceptions which allow students to access and use material which, in any other context, falls under the rubric of All Rights Reserved. These exceptions are certainly very useful, but for the purposes of this article I’m relying on the notion that to be truly literate, skills must be transferable to the world outside of education. After all, if we taught our students to write and spell but told them they couldn’t use the alphabet outside of school grounds, basic literacy for all would never have caught on!

Media, of course, doesn’t have just one alphabet; as an idea, in practice, and even the literal meaning of the word reminds us that media is multiple. That multiplicity holds particular challenges for education. How, for example, do we teach students to integrate sound, still images, moving images and text without spending enormous amounts of time creating each of these media forms individually? One option is to teach the theory behind media production without including practical elements. However, as contemporary pedagogical theory and most practicing educators would agree, the best way to help students fully understand and engage with a particular concept or area is to put that notion into practice. It follows, then, that while media literacies can be taught by just analysing and critiquing films, television and video, often the most profound way to engage students in developing critical understanding of the media is when students create their own. So, what’s needed then is access to media which students can use, adapt, remix and build upon which isn’t All Rights Reserved. Sure there’s material that’s in the public domain and has no copyright restrictions, but it takes a very long time for most media to enter the public domain these days (different media forms take different lengths of time, but 70 years or longer is the length that film, television and music remain off limits). More to the point, even though copyright is automatically assigned as soon as a work is made these days, many creators want others to be able to re-use their work in particular ways. That’s where the Creative Commons organisation becomes important, along with the range of copyright licenses they’ve developed which can allow creators to be a lot more specific about how their creative work can be re-used following the principle of Some Rights Reserved.

What Is It?

In a nutshell, the Creative Commons organisation began in 2001 with the explicit mission of trying to make innovation and creativity easier for the many people who create media which, to some extent, builds upon existing work. They recognised that because authors of creative work had only two choices when creating a piece of media – either following the All Rights Reserved model of full copyright or giving up any and all rights and putting their work in the Public Domain – these limited options meant most people went along with All Rights Reserved because they weren’t prepared to give up all of their rights as creators. Meanwhile, many authors said that they’d happily let others use portions of their work in specific ways – and when directly contacted often gave others explicit permission to do just that – but many people argued that a system which let authors say which freedoms they’d give to others would be make it a thousand times easier for new creative works to be made, remixing, mashing or borrowing from previous work. And that’s exactly what the Creative Commons organisation has done: they’ve developed a series of licenses that can let authors make clear what they’re happy for other people to do with that author’s work. While standard copyright notices make explicit what can’t be done with a particular work, Creative Commons licenses allow people to specify what can be done.

How Does It Work?

The Creative Commons organisation provides a set of simple-to-use tools which let authors specify the sort of things they will and won’t let other people do with their creative work. The fundaments of the Creative Commons licenses are these four elements:

- Attribution (BY): Attribution basically means that the author of a work must be acknowledged by anyone who uses that work in any way in the future.

- Non-Commercial (NC): Non-commercial simply means that the author’s work can be re-used but not for commercial purposes – ie you can’t make money selling this work as a whole or a derivative part of it in a new work.

- No Derivatives (ND): No derivatives means that you can’t alter the work and can only redistribute verbatim copies (so, for example, if it was a song you could download it, listen to it and share it, but you couldn’t take a sample from the song to use in your own work).

- Share-Alike (SA): Share-Alike specifies that any derivative works (ie a new work which includes this work in part or in whole) must be licensed in exactly the same way (so if the original license was a Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike license, then the new work created must use exactly the same licensing conditions).

These elements can thus be combined in different ways to form six possible Creative Commons licenses:

- Attribution: The work can be shared, sampled, re-mixed and so on as long as the original author of a work is acknowledged.

- Attribution, No Derivatives: The original author of a work must be acknowledged and no derivative works can be created using this piece (ie it can’t be sampled, bits can’t be used in new works).

- Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivatives License: Same as the previous license but with the extra stipulation that the work cannot be sold or distributed in any commercial manner.

- Attribution, Non-Commercial License: As long as authorship is acknowledged, the work can be used in any non-commercial way, including being sampled, remixed and so forth.

- Attribution, Non-Commercial, Share-Alike License: The same term as above, but with the added stipulation and all derivative works must be licensed using exactly the same terms.

- Attribution, Share-Alike License: So long as the original author of the work is acknowledged, it can be used, sampled and re-mixed as long as new works containing this piece are licensed under exactly the same terms.

While these licenses might sound a little confusing at times, it’s useful to think of them as the engine of the Creative Commons car: they need to be there to make everything work, but you don’t have to understand them in great detail in order to drive. Indeed, Creative Commons have set up a very simple website to help people choose a license, which is at http://creativecommons.org/license/. To choose a license, people just need to answer whether they want to allow commercial uses of their work and whether the want to allow modifications of their work and the website shows you the most appropriate license, complete with detailed instructions on how to add this license to your work (where your work can be anything from a document to an mp3 music file to a whole website).

But Isn’t Creative Commons American?

While the Creative Commons organisation is, indeed, based in the US, the great news is that there are local Creative Commons teams in many countries, including Australia. Apart from being extremely loud and clear advocates for Creative Commons across the board, from education though to entertainment, Creative Commons Australia (CCau) have also successfully implemented a national version of the Creative Commons licenses. This means that as educators, we can be 100% sure that Australian Creative Commons licenses will definitely be recognised in the Australia legal system. (This is especially significant since so many of the frustrating ambiguities in this area come from the fact that copyright laws differ across national boundaries.) When selecting a Creative Commons license using the website mentioned above, it’s also possible to simply select which jurisdiction you want to the license to fall under (so for Australia students and educators, ‘Australia’ is probably your best bet!).

Creative Commons in the Classroom

So, as an example, lets say that you’re a teacher of an upper secondary media class and you’ve asked the students to work in teams to create a short, topical, news report in a video format. They’ve got video cameras and editing software so can shoot the majority of the story themselves, but find during editing they need a few more bits of media: some music to jazz up the opening sequence, a couple of still images to use as cutaways during an interview, and some historical footage of the Olympic games (these students are doing a report on the Olympics, it turns out). Moreover, these students are hoping to post their news report on YouTube when they’re finished, showing it to family and friends. So, they’re going to need sources of secondary material that they have permission to re-use.

To find material, the students are already ahead of the game and head directly to the Creative Commons search portal (http://search.creativecommons.org) and they find some ‘fanfare’ music perfect for their opening sequence (the music has a Creative Commons Attribution license). Then the students click on a separate tab to search for images and find two amusing little images of the Chinese Olympics Mascots (Fuwa) and these are licensed using a Creative Commons, Attribution, Non-Commercial, Share-Alike license. Finally, the students head over to the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) and find some historical footage of the first ever Olympic Torch relay from the 1936 Olympics in Germany; this footage is old enough to be in the public domain. These secondary materials are added in and a brilliant story about Australia’s anticipation of the Olympic games is completed. Since their teacher has explained a bit about copyright and the Creative Commons, these students scan their secondary media and realise that with a combination of one public domain media piece, one using a Creative Commons Attribution license, and two using Creative Commons, Attribution, Non-Commercial, Share-Alike licenses, that their resulting news report will also need to be also licensed using a Creative Commons, Attribution, Non-Commercial, Share-Alike. The students hop onto the Creative Commons website, find a nifty little graphic file detailing their license, and place it as the final frame of their Olympic News Story.

Now, with a news story which can legally be re-distributed (as long as they don’t make money off it), this group of students post their video on YouTube. Their parents and peers are deeply impressed as it’s a great news story, and their clear understanding of copyright looks very professional! More to the point, a few weeks later the group of students get an email telling them that another group of students on the other side of the planet, in Canada, have included a clip from this Olympic News Report in a new student project in Canada, just as the Creative Commons license on that video allows them to do. Back in Australia the students and their teacher glow with pride knowing that they’ve not only created a wonderful news story, but it has also contributed to the global community and has been creatively built upon by others!

Introducing Creative Commons to Students

So you’re convinced about the value of Creative Commons licensing but can’t work out how to introduce them to your students? Thankfully, the Creative Commons folks have a lot of great media introducing their ethos, practice and licenses, all accessible via http://creativecommons.org/about/. Of particular use are the comic books which explain Creative Commons licenses via a superhero story, and a series of short web-based videos which introduce key Creative Commons ideas and features. Indeed, two of the best of these videos were produced by the Creative Commons Australia team, featuring the quirky animated characters Mayer and Bettle!

Where To Start?

So, you’re ready to give Creative Commons a go in your teaching and learning? Then here’s a few useful websites to get you started:

- www.creativecommons.org – The main website of the Creative Commons organisation with mountains of information.

- search.creativecommons.org – The search engine maintained by the Creative Commons organisation which lets you easily search many different databases for different media forms, all with Creative Commons licenses.

- creativecommons.org.au – The home of Creative Commons Australia and local efforts to promote the use and ethos of Creative Commons down under.

- www.archive.org – The Internet Archive, one of the world’s biggest repositories of historical material, a lot of which is either in the public domain or uses Creative Commons licenses. The Internet Archive has a lot of historical video material.

- www.flickr.com/creativecommons/ – The Creative Commons section of the massively popular photograph-sharing website Flickr has literally millions of different images available under Creative Commons licenses.

Battlestar Book (and Teaching with Facebook Updates?)

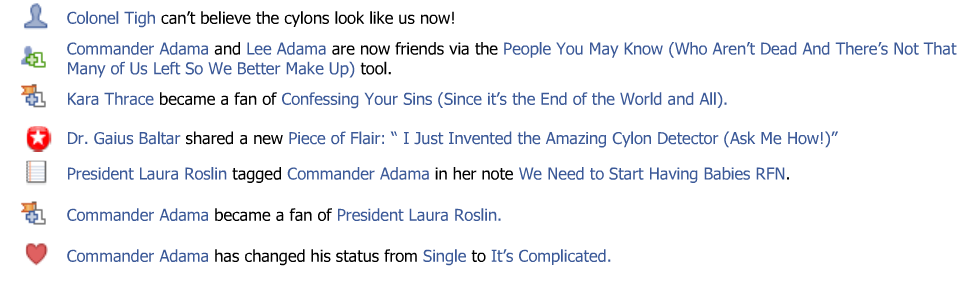

For anyone interesting in the convoluted social world of the soon-to-return Battlestar Galactica, you must check out the hilarious Battlestar Book which tells the tale of BSG in Facebook status updates. A snippet:

See the full Battlestar Book [Via io9].

Incidentally, does anyone know of an online generator or tool which can quickly knock out icon-driven status updates like these? After the Battlestar Book and the earlier hilarious Facebook Hamlet, I’m toying with the idea designing a project in which students summarise either a key article or perhaps episode of television using this style. I’m thinking it would get them to think critically about the sort of data Facebook gathers and shares about people while also encouraging students to brush up on their skills in terms of finding the key points and ideas in texts. Or is that nuts?

Annotated Digital Culture Links: January 1st 2009

Links for December 30th 2008 through January 1st 2009:

- Principles for a New Media Literacy by Dan Gillmor, 27 December 2008 [Center for Citizen Media] – “Principles of Media Creation: 1. Do your homework, and then do some more. … 2. Get it right, every time. … 3. Be fair to everyone. … 4. Think independently, especially of your own biases. … 5. Practice and demand transparency.””We are doing a poor job of ensuring that consumers and producers of media in a digital age are equipped for these tasks. This is a job for parents and schools. (Of course, a teacher who teaches critical thinking in much of the United States risks being attacked as a dangerous radical.) Do they have the resources — including time — that they need? But this much is clear: If we really believe that democracy requires an educated populace, we’re starting from a deficit. Are we ready to take the risk of being activist media users, for the right reasons? A lot rides on the answer.”

- Participative Pedagogy for a Literacy of Literacies by Howard Rheingold [Freesouls, ed. Joi Ito] – “Literacy−access to the codes and communities of vernacular video, microblogging, social bookmarking, wiki collaboration−is what is required to use that infrastructure to create a participatory culture. A population with broadband infrastructure and ubiquitous computing could be a captive audience for a cultural monopoly, given enough bad laws and judicial rulings. A population that knows what to do with the tools at hand stands a better chance of resisting enclosure. The more people who know how to use participatory media to learn, inform, persuade, investigate, reveal, advocate and organize, the more likely the future infosphere will allow, enable and encourage liberty and participation. Such literacy can only make action possible, however−it is not in the technology, or even in the knowledge of how to use it, but in the ways people use knowledge and technology to create wealth, secure freedom, resist tyranny.

- How to Do Everything with PDF Files [Adobe PDF Guide] – Pretty much anything you can imagine needing to do with PDF files, without needing to buy Acrobat!

- The 100 Most Popular Photoshop Tutorials 2008 [Photoshop Lady] – Many useful photoshop tutorials from fancy fonts to montages and entirely new creations!

- Israel posts video of Gaza air strikes on YouTube [Australian IT] – THE Israeli military has launched its own channel on video-sharing website YouTube, posting footage of air strikes and other attacks on Hamas militants in the Gaza Strip. The spokesman’s office of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) said it created the channel — youtube.com/user/idfnadesk — on Monday to “help us bring our message to the world.” The channel currently has more than 2,000 subscribers and hosts 10 videos, some of which have been viewed more than 20,000 times. The black-and-white videos include aerial footage of Israeli Air Force attacks on what are described as rocket launching sites, weapons storage facilities, a Hamas government complex and smuggling tunnels. One video shows what is described as a Hamas patrol boat being destroyed by a rocket fired from an Israeli naval vessel.”

- No terminating the Terminator … ever [ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)] – “Time will not be allowed to terminate The Terminator, the US Library of Congress said overnight. The low-budget 1984 action film, which spawned the popular catchphrase “I’ll be back”, was one of 25 movies listed for preservation by the library for their cultural, historic or aesthetic significance. Other titles included The Asphalt Jungle (1950), Deliverance (1972), A Face in the Crowd (1957), In Cold Blood (1967) and The Invisible Man (1933). The library said it selected The Terminator for preservation because of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s star-making performance as a cyborg assassin, and because the film stands out in the science fiction genre. “It’s withstood the test of time, like King Kong in a way, a film that endures because it’s so good,” Patrick Loughney, who runs the Library of Congress film vault, said.”

- Webisodes Bridge Gaps in NBC Series [NYTimes.com] – Takes a look at the late 2008/early 2009 webisodes from NBC (particularly for Heroes and Battlestar Galactica) and the way these online stories are used to keep fans engaged with television series (or, really, television-spawned franchises) during breaks.

- Nintendo to offer videos on Wii [WA Today] – “Nintendo will start offering videos through its blockbuster Wii game console, the latest new feature for the Japanese entertainment giant. Nintendo said it would develop original programming which Wii users could access via the internet and watch on their television. It is considering videos for both free and fees. The game giant teamed up with Japan’s leading advertising firm Dentsu to develop the service, which will begin in Japan next year, with an eye on future expansion into foreign markets.”

A Very CC Year …

As the Creative Commons movement celebrates a birthday this week, I thought I’d take the opportunity to reflect on my year in CC terms, as well as showing off some very impressive CC-licensed work by my honours students. It has already been a pretty big year in Creative Commons terms for me and the students I teach; in the first semester my Digital Media class experimented with Creative Commons licenses on a lot of their output, including many of their Student News reports and almost all of their outstanding Digital Media Projects; I’ve also enjoyed being part of an education panel at the Building an Australasian Commons conference in July, as well as presenting on my talk ‘Building Open Education Resources from the Bottom Up’ at the Open Education Resources Free Seminar in Brisbane in September.

As the year’s drawing to a close, I’m delighted to highlight one last effort, this time from the honours students in my iGeneration: Digital Communication and Participatory Culture course. The course, as in past years, has been a collaborative effort between the students and myself; I’ve provided the framing narrative and opening and closing weeks, while the students, in consultation, have written the central seminars in the course. Moreover, all course content from the seminars to the curriculum, from the students’ audio podcasts to their amazing remix videos, has been released under a Creative Commons license as both an exemplar of their fine work and an Open Educational Resource which, hopefully, will be something other teachers, students and creative citizens can draw upon for their own purposes. Moreover, given that I first ran iGeneration in 2005, this year’s students already built upon the work of that first cohort, learning from their peers and, hopefully, sharing so future peers can build on this work, too.

I also thought I’d take this opportunity to showcase some of the specific media projects created this year. The first is a really impressive podcast by Kiri Falls which looked at the Babelswarm art installation in Second Life …

[audio:http://igeneration.edublogs.org/files/2008/09/babelswarm.mp3][Full Sources & Exegesis] [CC BY NC SA]

Kiri’s final project for the unit, this time a remix video, takes quite literally the idea that creativity builds upon the past, with this enjoyable video which mashes together a plenitude of videos and photographs …

[Full Sources & Exegesis] [CC BY NC SA]

The second remix project I wanted to showcase is by Alex Pond; Alex has created a short but very poignant video which takes issue with the monolith that is copyright law, but celebrates the freedoms which are shared via the Creative Commons …

[Full Sources & Exegesis] [CC BY NC SA]

The final remix I wanted to highlight is a bit different. This one, by Chris Ardley, includes art and music from creators who’ve explicitly given Chris permission to re-use their work and share it under a CC license. This animation, created in Flash, explores remix more metaphorically, and tells a tale of worldly creation …

[Full Sources & Exegesis] [CC BY NC SA]

I think all of these projects are quite impressive, and I was delighted at how seriously this year’s students took the idea of remix and how many of them embraced everything that the Creative Commons has to offer, as well as giving back something of their own. I’ve also finally written iGeneration up as an educational example in the CC Case Studies Wiki, something I’ve been meaning to do for a while!

So, Happy 6th Birthday to the Creative Commons! In the next six years, I hope you’ll consider sharing work under a CC license if you haven’t already; a shared culture can help us all be a lot more creative. I know my students have benefitted from the generosity of the Creative Commons, and have, in turn, added a few quite impressive ideas and artefacts back into the creative stream.

Annotated Digital Culture Links: December 9th 2008

Links for December 9th 2008:

- Australia’s census going CC BY [Creative Commons] – “In a small, easy to miss post, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has made a very exciting announcement. They’re going CC – and under an Attribution-only license, no less. From the ABS website…

- Texting Turnbull catches the Twitter bug [The Age] – “As the Opposition’s popularity slips back to where it was under Brendan Nelson’s leadership, Opposition Leader Malcolm Turnbull is bringing digital intervention to the fore. The digits in question are his thumbs. Having witnessed the power of the web in the US presidential election campaign, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and Mr Turnbull are engaged in a high-tech arms race to win the hearts and minds of switched-on Australians. While some politicians including US President-elect Barack Obama are content with older model BlackBerry handsets, Mr Turnbull owns one of the latest releases, the BlackBerry Bold. And he showed off the speed of his thumbs as he settled once and for all the question of whether he writes his own Twitter updates. “I love technology,” he told online journalists in Sydney as he added another “tweet” via Twitter as they watched.” To his credit, more personal than a lot of Kevin07 stuff: http://twitter.com/turnbullmalcolm

- Virtual world for Muslims debuts [BBC NEWS | Technology] – “A trial version of the first virtual world aimed at the Muslim community has been launched. Called Muxlim Pal, it allows Muslims to look after a cartoon avatar that inhabits the virtual world. Based loosely on other virtual worlds such as The Sims, Muxlim Pal lets members customise the look of their avatar and its private room. Aimed at Muslims in Western nations, Muxlim Pal’s creators hope it will also foster understanding among non-Muslims. “We are not a religious site, we are a site that is focused on the lifestyle,” said Mohamed El-Fatatry, founder of Muxlim.com – the parent site of Muxlim Pal.”

- Facebook scandal shames students [The Age] – “A Facebook network of senior students from two of Sydney’s most elite private schools have offended the Jewish community with anti-Semitic slurs. Students from The Scots College in Bellevue Hill created a Facebook site called Jew Parking Appreciation Group which describes “Jew parking” as an art which often occurs at “Bellevue (Jew) Hill”. The site, which has 51 members, contains a link to The Scots Year 12 Boys, 2008, and The Scots College networks, and is administered by Scots students. It is connected to another network created and officiated by Scots College students with postings that include “support Holocaust denial” and a link to another internet address called “F— Israel and Their Holocaust Bullshit”.” (Racist rubbish, but also another example of supposedly ‘digital natives’ misunderstanding how much of their juvenile digital behaviour will be visible and recorded forever online.)

- Jean Burgess, Joshua Green – YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture [Polity Press] – “YouTube is one of the most well-known and widely discussed sites of participatory media in the contemporary online environment, and it is the first genuinely mass-popular platform for user-created video. In this timely and comprehensive introduction to how YouTube is being used and why it matters, Burgess and Green discuss the ways that it relates to wider transformations in culture, society and the economy.” (Potential textbook material for the Digital Media unit.)

- Learn at Any Time – The Open University [Podcasts] – The Open University podcasts website is a very well made example of university-based podcasts that DO NOT rely on hosting via Apple’s iTunes platform.