Home » social media

Category Archives: social media

Watching Musk fiddle while Twitter burns

Seeing Elon Musk pledge to reinstate Trump on Twitter understandably starts another wave of folks leaving the platform, but if we all leave Twitter, won’t it just become what Trump dreamed Parler would be?

I’ve been on Twitter for more than 15 years, and it’s the platform that has most felt like home for the majority of that time. I’m heartbroken by what Musk has managed to do to the platform and the people who (mostly used to, now) run it in a few short weeks. His flagrant disregard for users or the platform itself is gutting. (I’m with Nancy Baym on what’s being lost here, even if the platform stays online and doesn’t fall over.)

For better or worse, the media broadly (and academia in many ways, to be fair) has used Twitter as a proxy of public opinion. That won’t change overnight. If mostly moderate and left-leaning voices leave, does that give Trump via Musk exactly what he always wanted?

Trump gets Twitter as a pulpit to say whatever half-formed thought escapes his head, and a crowd of MAGA voices to cheer him on at every step. While the echo chamber idea has been widely challenged, it feels like this could be how that chamber would actually cohere.

From outside the US, that anyone, let alone a meaningful percentage, of US citizens believe the Biden election was ‘stolen’ feels like it shows exactly how powerful and destructive the Trump’s Twitter can be.

I don’t want to be putting dollars in Musk’s pocket either as he burns users and employees alike, but I’m deeply conflicted about just leaving the space which still has 15 years of ‘public square’ reputation. I don’t have a solution, but I have many fears.

And, yes, like many I’ve set up on Mastodon to see how that space evolves.

ABC Perth Spotlight forum: how to protect your privacy in an increasingly tech-driven world

I was pleased to be part of the ABC Perth Radio’s Spotlight Forum on ‘How to Protect Your Privacy in an Increasingly Tech-driven World‘ this morning, hosted by Nadia Mitsopoulos, and also featuring Associate Professor Julia Powles, Kathryn Gledhill-Tucker from Electronic Frontiers Australia and David Yates from Corrs Chambers Westgarth.

I was pleased to be part of the ABC Perth Radio’s Spotlight Forum on ‘How to Protect Your Privacy in an Increasingly Tech-driven World‘ this morning, hosted by Nadia Mitsopoulos, and also featuring Associate Professor Julia Powles, Kathryn Gledhill-Tucker from Electronic Frontiers Australia and David Yates from Corrs Chambers Westgarth.

You can stream the Forum on the ABC website, or download here.

Instagram’s privacy updates for kids are positive. But plans for an under-13s app means profits still take precedence

Shutterstock

By Tama Leaver, Curtin University

Facebook recently announced significant changes to Instagram for users aged under 16. New accounts will be private by default, and advertisers will be limited in how they can reach young people.

The new changes are long overdue and welcome. But Facebook’s commitment to childrens’ safety is still in question as it continues to develop a separate version of Instagram for kids aged under 13.

The company received significant backlash after the initial announcement in May. In fact, more than 40 US Attorneys General who usually support big tech banded together to ask Facebook to stop building the under-13s version of Instagram, citing privacy and health concerns.

Privacy and advertising

Online default settings matter. They set expectations for how we should behave online, and many of us will never shift away from this by changing our default settings.

Adult accounts on Instagram are public by default. Facebook’s shift to making under-16 accounts private by default means these users will need to actively change their settings if they want a public profile. Existing under-16 users with public accounts will also get a prompt asking if they want to make their account private.

These changes normalise privacy and will encourage young users to focus their interactions more on their circles of friends and followers they approve. Such a change could go a long way in helping young people navigate online privacy.

Facebook has also limited the ways in which advertisers can target Instagram users under age 18 (or older in some countries). Instead of targeting specific users based on their interests gleaned via data collection, advertisers can now only broadly reach young people by focusing ads in terms of age, gender and location.

This change follows recently publicised research that showed Facebook was allowing advertisers to target young users with risky interests — such as smoking, vaping, alcohol, gambling and extreme weight loss — with age-inappropriate ads.

This is particularly worrying, given Facebook’s admission there is “no foolproof way to stop people from misrepresenting their age” when joining Instagram or Facebook. The apps ask for date of birth during sign-up, but have no way of verifying responses. Any child who knows basic arithmetic can work out how to bypass this gateway.

Of course, Facebook’s new changes do not stop Facebook itself from collecting young users’ data. And when an Instagram user becomes a legal adult, all of their data collected up to that point will then likely inform an incredibly detailed profile which will be available to facilitate Facebook’s main business model: extremely targeted advertising.

Deploying Instagram’s top dad

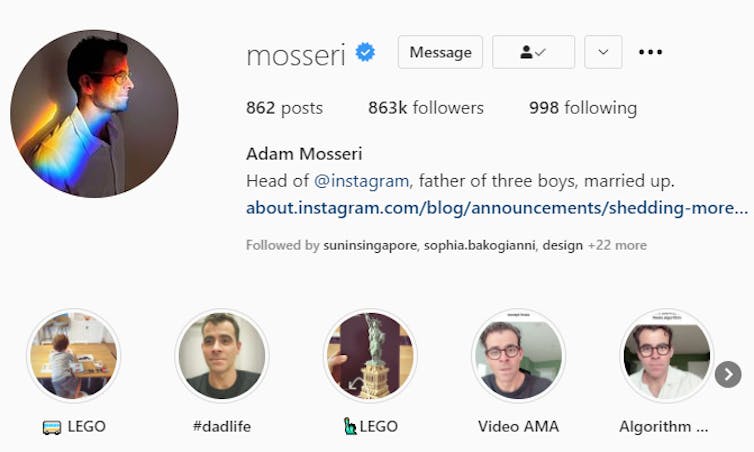

Facebook has been highly strategic in how it released news of its recent changes for young Instagram users. In contrast with Facebook’s chief executive Mark Zuckerberg, Instagram’s head Adam Mosseri has turned his status as a parent into a significant element of his public persona.

Since Mosseri took over after Instagram’s creators left Facebook in 2018, his profile has consistently emphasised he has three young sons, his curated Instagram stories include #dadlife and Lego, and he often signs off Q&A sessions on Instagram by mentioning he needs to spend time with his kids.

When Mosseri posted about the changes for under-16 Instagram users, he carefully framed the news as coming from a parent first, and the head of one of the world’s largest social platforms second. Similar to many influencers, Mosseri knows how to position himself as relatable and authentic.

Age verification and ‘potentially suspicious’ adults

In a paired announcement on July 27, Facebook’s vice-president of youth products Pavni Diwanji announced Facebook and Instagram would be doing more to ensure under-13s could not access the services.

Diwanji said Facebook was using artificial intelligence algorithms to stop “adults that have shown potentially suspicious behavior” from being able to view posts from young people’s accounts, or the accounts themselves. But Facebook has not offered an explanation as to how a user might be found to be “suspicious”.

Diwanji notes the company is “building similar technology to find and remove accounts belonging to people under the age of 13”. But this technology isn’t being used yet.

It’s reasonable to infer Facebook probably won’t actively remove under-13s from either Instagram or Facebook until the new Instagram For Kids app is launched — ensuring those young customers aren’t lost to Facebook altogether.

Despite public backlash, Diwanji’s post confirmed Facebook is indeed still building “a new Instagram experience for tweens”. As I’ve argued in the past, an Instagram for Kids — much like Facebook’s Messenger for Kids before it — would be less about providing a gated playground for children and more about getting children familiar and comfortable with Facebook’s family of apps, in the hope they’ll stay on them for life.

A Facebook spokesperson told The Conversation that a feature introduced in March prevents users registered as adults from sending direct messages to users registered as teens who are not following them.

“This feature relies on our work to predict peoples’ ages using machine learning technology, and the age people give us when they sign up,” the spokesperson said.

They said “suspicious accounts will no longer see young people in ‘Accounts Suggested for You’, and if they do find their profiles by searching for them directly, they won’t be able to follow them”.

Resources for parents and teens

For parents and teen Instagram users, the recent changes to the platform are a useful prompt to begin or to revisit conversations about privacy and safety on social media.

Instagram does provide some useful resources for parents to help guide these conversations, including a bespoke Australian version of their Parent’s Guide to Instagram created in partnership with ReachOut. There are many other online resources, too, such as CommonSense Media’s Parents’ Ultimate Guide to Instagram.

Regarding Instagram for Kids, a Facebook spokesperson told The Conversation the company hoped to “create something that’s really fun and educational, with family friendly safety features”.

But the fact that this app is still planned means Facebook can’t accept the most straightforward way of keeping young children safe: keeping them off Facebook and Instagram altogether.

![]()

Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Future Of Children’s Online Privacy

I was delighted to join Dr Anna Bunn, Deputy Head of Curtin Law School, and the Future Of team for a podcast interview all about Children’s Online Privacy.

The half hour podcast is online here in various formats, including shownotes, or embedded in this post:

We discuss:

What’s the impact of parents sharing content of their children online? And what rights do children have in this space?

In this episode, Jessica is joined by Dr Anna Bunn, Deputy Head of Curtin Law School and Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies at Curtin University to discuss “sharenting” – the growing practice of parents sharing images and data of their children online. The three examine the social, legal and developmental impacts a life-long digital footprint can have on a child.

- What is the impact of sharing child-related content on our kids? [04:08]

- What type of tools and legal protections would you like to see in the future to protect children? [16:30]

- At what age can a child give consent to share content [18:25]

- What about the right to be forgotten [21:11]

- What’s best practice for sharing child-related content online? [26:01]

Happy birthday Instagram! 5 ways doing it for the ‘gram has changed us

6 October 2020 marks Instagram’s tenth birthday. Having amassed more than a billion active users worldwide, the app has changed radically in that decade. And it has changed us.

1. Instagram’s evolution

When it was launched on October 6, 2010 by Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, Instagram was an iPhone-only app. The user could take photos (and only take photos — the app could not load existing images from the phone’s gallery) within a square frame. These could be shared, with an enhancing filter if desired. Other users could comment or like the images. That was it.

As we chronicle in our book, the platform has grown rapidly and been at the forefront of an increasingly visual social media landscape.

In 2012, Facebook purchased Instagram for a deal worth a $US1 billion (A$1.4 billion), which in retrospect probably seems cheap. Instagram is now one of the most profitable jewels in the Facebook crown.

Instagram has integrated new features over time, but it did not invent all of them.

Instagram Stories, with more than half a billion daily users, was shamelessly borrowed from Snapchat in 2016. It allowed users to post 10-second content bites which disappear after 24 hours. The rivers of casual and intimate content (later integrated into Facebook) are widely considered to have revitalised the app.

Similarly, IGTV is Instagram’s answer to YouTube’s longer-form video. And if the recently-released Reels isn’t a TikTok clone, we’re not sure what else it could be.

Read more: Facebook is merging Messenger and Instagram chat features. It’s for Zuckerberg’s benefit, not yours

2. Under the influencers

Instagram is largely responsible for the rapid professionalisation of the influencer industry. Insiders estimated the influencer industry would grow to US$9.7 billion (A$13.5 billion) in 2020, though COVID-19 has since taken a toll on this as with other sectors.

As early as in 2011, professional lifestyle bloggers throughout Southeast Asia were moving to Instagram, turning it into a brimming marketplace. They sold ad space via post captions and monetised selfies through sponsored products. Such vernacular commerce pre-dates Instagram’s Paid Partnership feature, which launched in late-2017.

The use of images as a primary mode of communication, as opposed to the text-based modes of the blogging era, facilitated an explosion of aspiring influencers. The threshold for turning oneself into an online brand was dramatically lowered.

Instagrammers relied more on photography and their looks — enhanced by filters and editing built into the platform.

Soon, the “extremely professional and polished, the pretty, pristine, and picturesque” started to become boring. Finstagrams (“fake Instagram”) and secondary accounts proliferated and allowed influencers to display behind-the-scenes snippets and authenticity through calculated performances of amateurism.

3. Instabusiness as usual

As influencers commercialised Instagram captions and photos, those who had owned online shops turned hashtag streams into advertorial campaigns. They relied on the labour of followers to publicise their wares and amplify their reach.

Bigger businesses followed suit and so did advice from marketing experts for how best to “optimise” engagement.

In mid-2016, Instagram belatedly launched business accounts and tools, allowing companies easy access to back-end analytics. The introduction of the “swipeable carousel” of story content in early 2017 further expanded commercial opportunities for businesses by multiplying ad space per Instagram post. This year, in the tradition of Instagram corporatising user innovations, it announced Instagram Shops would allow businesses to sell products directly via a digital storefront. Users had previously done this via links.

Read more: Friday essay: Twitter and the way of the hashtag

4. Sharenting

Instagram isn’t just where we tell the visual story of ourselves, but also where we co-create each other’s stories. Nowhere is this more evident than the way parents “sharent”, posting their children’s daily lives and milestones.

Many children’s Instagram presence begins before they are even born. Sharing ultrasound photos has become a standard way to announce a pregnancy. Over 1.5 million public Instagram posts are tagged #genderreveal.

Sharenting raises privacy questions: who owns a child’s image? Can children withdraw publishing permission later?

Sharenting entails handing over children’s data to Facebook as part of the larger realm of surveillance capitalism. A saying that emerged around the same time as Instagram was born still rings true: “When something online is free, you’re not the customer, you’re the product”. We pay for Instagram’s “free” platform with our user data and our children’s data, too, when we share photos of them.

Read more: The real problem with posting about your kids online

5. Seeing through the frame

The apparent “Instagrammability” of a meal, a place, or an experience has seen the rise of numerous visual trends and tropes.

Short-lived Instagram Stories and disappearing Direct Messages add more spaces to express more things without the threat of permanence.

Read more: Friday essay: seeing the news up close, one devastating post at a time

The events of 2020 have shown our ways of seeing on Instagram reveal the possibilities and pitfalls of social media.

In June racial justice activism on #BlackoutTuesday, while extremely popular, also had the effect of swamping the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag with black squares.

Instagram is rife with disinformation and conspiracy theories which hijack the look and feel of authoritive content. The template of popular Instagram content can see familiar aesthetics weaponised to spread misinformation.

Ultimately, the last decade has seen Instagram become one of the main lenses through which we see the world, personally and politically. Users communicate and frame the lives they share with family, friends and the wider world.

Read more: #travelgram: live tourist snaps have turned solo adventures into social occasions

Tama Leaver, Associate Professor in Internet Studies, Curtin University; Crystal Abidin, Senior Research Fellow & ARC DECRA, Internet Studies, Curtin University, Curtin University, and Tim Highfield, Lecturer in Digital Media and Society, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Reflections and Resources from the 2017 Digitising Early Childhood Conference

Last week’s Digitising Early Childhood conference here in Perth was a fantastic event which brought together so many engaging and provocative scholars in a supportive and policy/action-orientated environment (which I suppose I should call ‘engagement and impact’-orientated in Australia right now). For a pretty well document overview of the conference itself, you can see the quite substantial tweets collected via the #digikids17 hashtag on Twitter, which I’d really encourage you to look over. My head is still buzzing, so instead to trying to synthesise everyone else’s amazing work, I’m just going to quickly point to the material that arose my three different talks in case anyone wishes to delve further.

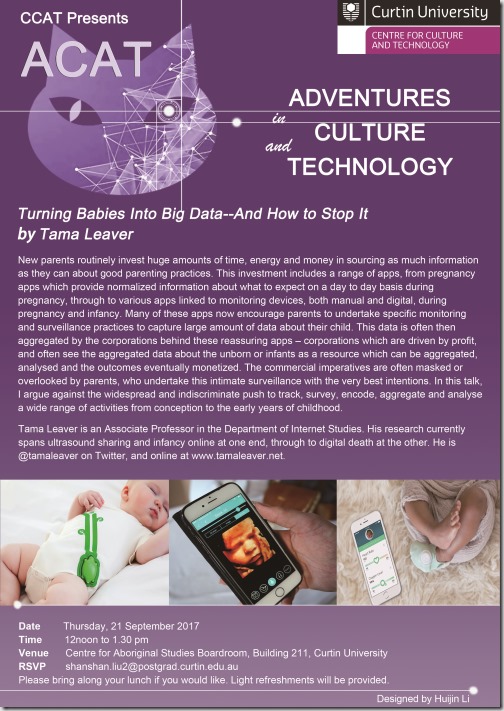

First up, here are the slides for my keynote ‘Turning Babies into Big Data—And How to Stop It’:

If you’d like to hear the talk that goes with the slides, there’s an audio recording you can download here. (I think these were filmed, so if a link becomes available at some point, I’ll update and post it here.) There was a great response to my talk, which was humbling and gratifying at the same time. There was also quite a lot of press interest, too, so here’s the best pieces that are available online (and may prove a more accessible overview of some of the issues I explored):

If you’d like to hear the talk that goes with the slides, there’s an audio recording you can download here. (I think these were filmed, so if a link becomes available at some point, I’ll update and post it here.) There was a great response to my talk, which was humbling and gratifying at the same time. There was also quite a lot of press interest, too, so here’s the best pieces that are available online (and may prove a more accessible overview of some of the issues I explored):

- Rebecca Turner’s ABC article ‘Owlet Smark Sock prompts warning for parents, fears over babies’ sensitive health data’;

- Leon Compton’s interview on ABC Radio Tasmania ‘Social media and parenting: the do’s and don’ts’ (audio);

- Brigid O’Connell’s Herald Sun story, Parents may be unwittingly turning babies into big data (paywalled); and

- Cathy O’Leary’s story in The Western Australian, Parents airing kids’ lives on social media.

While our argument is still being polished, the slides for this version of Crystal Abidin and my paper From YouTube to TV, and back again: Viral video child stars and media flows in the era of social media are also available:

This paper began as a discussion after our piece about Daddy O Five in The Conversation and where the complicated questions about children in media first became prominent. Crystal wasn’t able to be there in person, but did a fantastic Snapchat-recorded 5-minute intro, while I brought home the rest of the argument live. Crystal has a great background page on her website, linking this to her previous work in the area. There was also press interest in this talk, and the best piece to listen to (and hear Crystal and I in dialogue, even though this was recorded at different times, on different continents!):

- Brett Worthington’s Life Matters segment on Radio National, How social media videos turn children into viral sensations (audio)

Finally, as part of the Higher Degree by Research and Early Career Researcher Day which ended the conference, I presented a slightly updated version of my workshop ‘Developing a scholarly web presence & using social media for research networking’:

Overall, it was a very busy, but very rewarding conference, with new friends made, brilliant new scholarship to digest, and surely some exciting new collaborations begun!

[Photo of the Digitising Early Childhood Conference Keynote Speakers]

Three Upcoming Infancy Online-related events

Over the next month, I’m lucky enough to be involved in three separate events focused on infancy online, digital media and early childhood. The details …

[1] Thinking the Digital: Children, Young People and Digital Practice – Friday, 8th September, Sydney – is co-hosted by the Office of the eSafety Commissioner; Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University; and Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney. The event opens with a keynote by visiting LSE Professor Sonia Livingstone, and is followed by three sessions discussing youth, childhood and the digital age is various forms. While Sonia Livingstone is reason enough to be there, the three sessions are populated by some of the best scholars in Australia, and it should be a really fantastic discussion. I’ll be part of the second session on Rights-based Approaches to Digital Research, Policy and Practice. There are limited places, and a small fee, involved if you’re interested in attending, so registration is a must! To follow along on Twitter, the official hashtag is #ThinkingTheDigital.

The day before this event, Sonia Livingston is also giving a public seminar at WSU’s Parramatta City campus if you’re in able to attend on the afternoon of Thursday, 7th September.

[2] The following week is the big Digitising Early Childhood International Conference 2017 which runs 11-15 September, features a great line-up of keynotes as well as a truly fascinating range of papers on early childhood in the digital age. I’m lucky enough to be giving the conference’s first keynote on Tuesday morning, entitled ‘Turning Babies into Big Data–And How to Stop it’. I’ll also be presenting Crystal Abidin and my paper ‘From YouTube to TV, and Back Again: Viral Video Child Stars and Media Flows in the Era of Social Media‘ on the Wednesday and running a session on the final day called ‘Strategies for Developing a Scholarly Web Presence during a Higher Degree & Early Career’ as part of the Higher Degree by Research/Early Career Researcher Day. It should be a very busy, but also incredibly engaging week! To follow tweets from conference, the official hashtag is #digikids17.

[3] Finally, as part of Research and Innovation Week 2017 at Curtin University, at midday on Thursday 21st September I’ll be presenting a slightly longer version of my talk Turning Babies into Big Data—and How to Stop It in the Adventures in Culture and Technology series hosted by Curtin’s Centre for Culture and Technology. This is a free talk, open to anyone, but please either RSVP to this email, or use the Facebook event page to indicate you’re coming.

When exploiting kids for cash goes wrong on YouTube: the lessons of DaddyOFive

A new piece in The Conversation from Crystal Abidin and me …

Tama Leaver, Curtin University and Crystal Abidin, Curtin University

The US YouTube channel DaddyOFive, which features a husband and wife from Maryland “pranking” their children, has pulled all its videos and issued a public apology amid allegations of child abuse.

The “pranks” would routinely involve the parents fooling their kids into thinking they were in trouble, screaming and swearing at them, only the reveal “it was just a prank” as their children sob on camera.

Despite its removal the content continues to circulate in summary videos from Philip DeFranco and other popular YouTubers who are critiquing the DaddyOFive channel. And you can still find videos of parents pranking their children on other channels around YouTube. But the videos also raise wider issues about children in online media, particularly where the videos make money. With over 760,000 subscribers, it is estimated that DaddyOFive earned between US$200,000-350,000 each year from YouTube advertising revenue.

The rise of influencers

Kid reactions on YouTube are a popular genre, with parents uploading viral videos of their children doing anything from tasting lemons for the first time to engaging in baby speak. Such videos pre-date the internet, with America’s Funniest Home Videos (1989-) and other popular television shows capitalising on “kid moments”.

In the era of mobile devices and networked communication, the ease with which children can be documented and shared online is unprecedented. Every day parents are “sharenting”, archiving and broadcasting images and videos of their children in order to share the experience with friends.

Even with the best intentions, though, one of us (Tama) has argued that photos and videos shared with the best of intentions can inadvertently lead to “intimate surveillance”, where online platforms and corporations use this data to build detailed profiles of children.

YouTube and other social media have seen the rise of influencer commerce, where seemingly ordinary users start featuring products and opinions they’re paid to share. By cultivating personal brands through creating a sense of intimacy with their consumers, these followings can be strong enough for advertisers to invest in their content, usually through advertorials and product placements. While the DaddyOFive channel was clearly for-profit, the distinction between genuine and paid content is often far from clear.

From the womb to celebrity

As with DaddyOFive, these influencers can include entire families, including children whose rights to participate, or choose not to participate, may not always be considered. In some cases, children themselves can be the star, becoming microcelebrities, often produced and promoted by their parents.

South Korean toddler Yebin, for instance, first went viral as a three-year-old in 2014 in a video where her mom was teaching her to avoid strangers. Since then, Yebin and her younger brother have been signed to influencer agencies to manage their content, based on the reach of their channel which has accumulated over 21 million views.

As viral videos become marketable and kid reaction videos become more lucrative, this may well drive more and more elaborate situations and set-ups. Yet, despite their prominence on social media, such children in internet-famous families are not clearly covered by the traditional workplace standards (such as Child Labour Laws and that Coogan Law in the US), which historically protected child stars in mainstream media industries from exploitation.

This is concerning especially since not only are adult influencers featuring their children in advertorials and commercial content, but some are even grooming a new generation of “micro-microcelebrities” whose celebrity and careers begin in the womb.

In the absence of any formal guidelines for the child stars of social media, it is the peers and corporate platforms that are policing the welfare of young children. As prominent YouTube influencers have rallied to denounce the parents behind the DaddyOFive accusing them of child abuse, they have also leveraged their influence to report the parents of DaddyOFive to child protective services. YouTube has also reportedly responded initially by pulling advertising from the channel. YouTubers collectively demonstrating a shared moral position is undoubtedly helpful.

Greater transparency

The question of children, commerce and labour on social media is far from limited to YouTube. Australian PR director Roxy Jacenko has, for example, defended herself against accusations of exploitation after launching and managing a commercial Instagram account for her her young daughter Pixie, who at three-years-old was dubbed the “Princess of Instagram”. And while Jacenko’s choices for Pixie may differ from many other parents, at least as someone in PR she is in a position to make informed and articulated choices about her daughter’s presence on social media.

Already some influencers are assuring audiences that child participation is voluntary, enjoyable, and optional by broadcasting behind-the-scenes footage.

Television, too, is making the most of children on social media. The Ellen DeGeneres Show, for example, regularly mines YouTube for viral videos starring children in order to invite them as guests on the show. Often they are invited to replicate their viral act for a live audience, and the show disseminates these program clips on its corporate YouTube channel, sometimes contracting viral YouTube children with high attention value to star in their own recurring segments on the show.

Ultimately, though, children appearing on television are subject to laws and regulations that attempt to protect their well-being. On for-profit channels on YouTube and other social media platforms there is a little transparency about the role children are playing, the conditions of their labour, and how (and if) they are being compensated financially.

Children may be a one-off in parents’ videos, or the star of the show, but across this spectrum, social media like YouTube need rules to ensure that children’s participation is transparent and their well-being paramount.

Tama Leaver, Associate Professor in Internet Studies, Curtin University and Crystal Abidin, Adjunct Research Fellow at the Centre for Culture and Technology (CCAT), Curtin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Two New ARticles

Two new articles …

[X] Visualising the Ends of Identity: Pre-Birth and Post-Death on Instagram in Information, Communication and Society by me and Tim Highfield. This is one of the first Ends of Identity article coming from our big Instagram dataset, analysing the first year (2014). We’ll be writing more looking at the three years we collected (14-16) before the Instagram APIs changed and locked us out! Here’s the abstract:

[X] Visualising the Ends of Identity: Pre-Birth and Post-Death on Instagram in Information, Communication and Society by me and Tim Highfield. This is one of the first Ends of Identity article coming from our big Instagram dataset, analysing the first year (2014). We’ll be writing more looking at the three years we collected (14-16) before the Instagram APIs changed and locked us out! Here’s the abstract:

This paper examines two ‘ends’ of identity online – birth and death – through the analytical lens of specific hashtags on the Instagram platform. These ends are examined in tandem in an attempt to surface commonalities in the way that individuals use visual social media when sharing information about other people. A range of emerging norms in digital discourses about birth and death are uncovered, and it is significant that in both cases the individuals being talked about cannot reply for themselves. Issues of agency in representation therefore frame the analysis. After sorting through a number of entry points, images and videos with the #ultrasound and #funeral hashtags were tracked for three months in 2014. Ultrasound images and videos on Instagram revealed a range of communication and representation strategies, most highlighting social experiences and emotional peaks. There are, however, also significant privacy issues as a significant proportion of public accounts share personally identifiable metadata about the mother and unborn child, although these issue are not apparent in relation to funeral images. Unlike other social media platforms, grief on Instagram is found to be more about personal expressions of loss rather than affording spaces of collective commemoration. A range of related practices and themes, such as commerce and humour, were also documented as a part of the spectrum of activity on the Instagram platform. Norms specific to each collection emerged from this analysis, which are then compared to document research about other social media platforms, especially Facebook.

You can read the paper online here, or if the paywall gets in your way there’s a pre-print available via Academia.edu.

[X] Instagrammatics and digital methods: studying visual social media, from selfies and GIFs to memes and emoji in Communication, Research and Practice, also authored by Tim Highfield and me. This paper came out earlier in the year, but I forgot to mention it here. The abstract:

Visual content is a critical component of everyday social media, on platforms explicitly framed around the visual (Instagram and Vine), on those offering a mix of text and images in myriad forms (Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr), and in apps and profiles where visual presentation and provision of information are important considerations. However, despite being so prominent in forms such as selfies, looping media, infographics, memes, online videos, and more, sociocultural research into the visual as a central component of online communication has lagged behind the analysis of popular, predominantly text-driven social media. This paper underlines the increasing importance of visual elements to digital, social, and mobile media within everyday life, addressing the significant research gap in methods for tracking, analysing, and understanding visual social media as both image-based and intertextual content. In this paper, we build on our previous methodological considerations of Instagram in isolation to examine further questions, challenges, and benefits of studying visual social media more broadly, including methodological and ethical considerations. Our discussion is intended as a rallying cry and provocation for further research into visual (and textual and mixed) social media content, practices, and cultures, mindful of both the specificities of each form, but also, and importantly, the ongoing dialogues and interrelations between them as communication forms.

This paper is free to read online until at least the end of 2016, but if a paywall comes up, there’s a pre-print of this one of Academia.edu, too.

Intimate Surveillance: Normalizing Parental Monitoring and Mediation of Infants Online

At yesterday’s outstanding Controlling Data: Somebody Think of the Children symposium I presented the first version of my new paper “Intimate Surveillance: Normalizing Parental Monitoring and Mediation of Infants Online.” Here’s the abstract:

Parents are increasingly sharing information about infants online in various forms and capacities. In order to more meaningfully understand the way parents decide what to share about young people, and the way those decisions are being shaped, this paper focuses on two overlapping areas: parental monitoring of babies and infants through the example of wearable technologies; and parental mediation through the example of the public sharing practices of celebrity and influencer parents. The paper begins by contextualizing these parental practices within the literature on surveillance, with particular attention to online surveillance and the increasing importance of affect. It then gives a brief overview of work on pregnancy mediation, monitoring on social media, and via pregnancy apps, which is the obvious precursor to examining parental sharing and monitoring practices regarding babies and infants. The examples of parental monitoring and parental mediation will then build on the idea of “intimate surveillance” which entails close and seemingly invasive monitoring by parents. Parental monitoring and mediation contribute to the normalization of intimate surveillance to the extent that surveillance is (re)situated as a necessary culture of care. The choice to not survey infants is thus positioned, worryingly, as a failure of parenting.

An mp3 recording of the audio is available, and the slides are below:

The full version of this paper is currently under review, but if you’re interested in reading the draft, just email me.