Web’s inventor says news media bargaining code could break the internet. He’s right — but there’s a fix

Tama Leaver, Curtin University

The inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, has raised concerns that Australia’s proposed News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code could fundamentally break the internet as we know it.

His concerns are valid. However, they could be addressed through minor changes to the proposed code.

How could the code break the web?

The news media bargaining code aims to level the playing field between media companies and online giants. It would do this by forcing Facebook and Google to pay Australian news businesses for content linked to, or featured, on their platforms.

In a submission to the Senate inquiry about the code, Berners-Lee wrote:

Specifically, I am concerned that the Code risks breaching a fundamental principle of the web by requiring payment for linking between certain content online. […] The ability to link freely — meaning without limitations regarding the content of the linked site and without monetary fees — is fundamental to how the web operates.

Currently, one of the most basic underlying principles of the web is there is no cost involved in creating a hypertext link (or simply a “link”) to any other page or object online.

When Berners-Lee first devised the World Wide Web in 1989, he effectively gave away the idea and associated software for free, to ensure nobody would or could charge for using its protocols.

He argues the news media bargaining code could set a legal precedent allowing someone to charge for linking, which would let the genie out of the bottle — and plenty more attempts to charge for linking to content would appear.

If the precedent were set that people could be charged for simply linking to content online, it’s possible the underlying principle of linking would be disrupted.

As a result, there would likely be many attempts by both legitimate companies and scammers to charge users for what is currently free.

While supporting the “right of publishers and content creators to be properly rewarded for their work”, Berners-Lee asks the code be amended to maintain the principle of allowing free linking between content.

Google and Facebook don’t just link to content

Part of the issue here is Google and Facebook don’t just collect a list of interesting links to news content. Rather the way they find, sort, curate and present news content adds value for their users.

They don’t just link to news content, they reframe it. It is often in that reframing that advertisements appear, and this is where these platforms make money.

For example, this link will take you to the original 1989 proposal for the World Wide Web. Right now, anyone can create such a link to any other page or object on the web, without having to pay anyone else.

But what Facebook and Google do in curating news content is fundamentally different. They create compelling previews, usually by offering the headline of a news article, sometimes the first few lines, and often the first image extracted.

For instance, here is a preview Google generates when someone searches for Tim Berners-Lee’s Web proposal:

Evidently, what Google returns is more of a media-rich, detailed preview than a simple link. For Google’s users, this is a much more meaningful preview of the content and better enables them to decide whether they’ll click through to see more.

Another huge challenge for media businesses is that increasing numbers of users are taking headlines and previews at face value, without necessarily reading the article.

This can obviously decrease revenue for news providers, as well as perpetuate misinformation. Indeed, it’s one of the reasons Twitter began asking users to actually read content before retweeting it.

A fairly compelling argument, then, is that Google and Facebook add value for consumers via the reframing, curating and previewing of content — not just by linking to it.

Can the code be fixed?

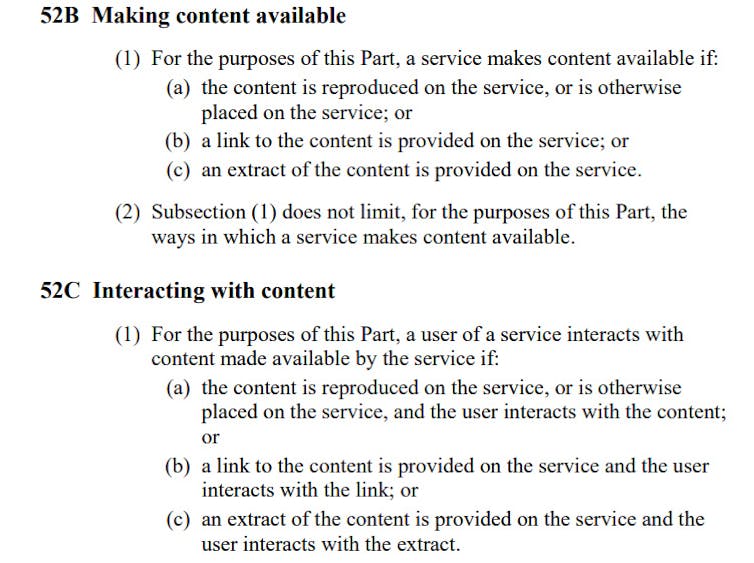

Currently in the code, the section concerning how platforms are “Making content available” lists three ways content is shared:

- content is reproduced on the service

- content is linked to

- an extract or preview is made available.

Similar terms are used to detail how users might interact with content.

Australian Government

If we accept most of the additional value platforms provide to their users is in curating and providing previews of content, then deleting the second element (which just specifies linking to content) would fix Berners-Lee’s concerns.

It would ensure the use of links alone can’t be monetised, as has always been true on the web. Platforms would still need to pay when they present users with extracts or previews of articles, but not when they only link to it.

Since basic links are not the bread and butter of big platforms, this change wouldn’t fundamentally alter the purpose or principle of creating a more level playing field for news businesses and platforms.

In its current form, the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code could put the underlying principles of the world wide web in jeopardy. Tim Berners-Lee is right to raise this point.

But a relatively small tweak to the code would prevent this, It would allow us to focus more on where big platforms actually provide value for users, and where the clearest justification lies in asking them to pay for news content.

For transparency, it should be noted The Conversation has also made a submission to the Senate inquiry regarding the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code.![]()

Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Happy birthday Instagram! 5 ways doing it for the ‘gram has changed us

Tama Leaver, Curtin University; Crystal Abidin, Curtin University, and Tim Highfield, University of Sheffield

6 October 2020 marks Instagram’s tenth birthday. Having amassed more than a billion active users worldwide, the app has changed radically in that decade. And it has changed us.

1. Instagram’s evolution

When it was launched on October 6, 2010 by Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, Instagram was an iPhone-only app. The user could take photos (and only take photos — the app could not load existing images from the phone’s gallery) within a square frame. These could be shared, with an enhancing filter if desired. Other users could comment or like the images. That was it.

As we chronicle in our book, the platform has grown rapidly and been at the forefront of an increasingly visual social media landscape.

In 2012, Facebook purchased Instagram for a deal worth a $US1 billion (A$1.4 billion), which in retrospect probably seems cheap. Instagram is now one of the most profitable jewels in the Facebook crown.

Instagram has integrated new features over time, but it did not invent all of them.

Instagram Stories, with more than half a billion daily users, was shamelessly borrowed from Snapchat in 2016. It allowed users to post 10-second content bites which disappear after 24 hours. The rivers of casual and intimate content (later integrated into Facebook) are widely considered to have revitalised the app.

Similarly, IGTV is Instagram’s answer to YouTube’s longer-form video. And if the recently-released Reels isn’t a TikTok clone, we’re not sure what else it could be.

Read more: Facebook is merging Messenger and Instagram chat features. It’s for Zuckerberg’s benefit, not yours

2. Under the influencers

Instagram is largely responsible for the rapid professionalisation of the influencer industry. Insiders estimated the influencer industry would grow to US$9.7 billion (A$13.5 billion) in 2020, though COVID-19 has since taken a toll on this as with other sectors.

As early as in 2011, professional lifestyle bloggers throughout Southeast Asia were moving to Instagram, turning it into a brimming marketplace. They sold ad space via post captions and monetised selfies through sponsored products. Such vernacular commerce pre-dates Instagram’s Paid Partnership feature, which launched in late-2017.

The use of images as a primary mode of communication, as opposed to the text-based modes of the blogging era, facilitated an explosion of aspiring influencers. The threshold for turning oneself into an online brand was dramatically lowered.

Instagrammers relied more on photography and their looks — enhanced by filters and editing built into the platform.

Soon, the “extremely professional and polished, the pretty, pristine, and picturesque” started to become boring. Finstagrams (“fake Instagram”) and secondary accounts proliferated and allowed influencers to display behind-the-scenes snippets and authenticity through calculated performances of amateurism.

3. Instabusiness as usual

As influencers commercialised Instagram captions and photos, those who had owned online shops turned hashtag streams into advertorial campaigns. They relied on the labour of followers to publicise their wares and amplify their reach.

Bigger businesses followed suit and so did advice from marketing experts for how best to “optimise” engagement.

In mid-2016, Instagram belatedly launched business accounts and tools, allowing companies easy access to back-end analytics. The introduction of the “swipeable carousel” of story content in early 2017 further expanded commercial opportunities for businesses by multiplying ad space per Instagram post. This year, in the tradition of Instagram corporatising user innovations, it announced Instagram Shops would allow businesses to sell products directly via a digital storefront. Users had previously done this via links.

Read more: Friday essay: Twitter and the way of the hashtag

4. Sharenting

Instagram isn’t just where we tell the visual story of ourselves, but also where we co-create each other’s stories. Nowhere is this more evident than the way parents “sharent”, posting their children’s daily lives and milestones.

Many children’s Instagram presence begins before they are even born. Sharing ultrasound photos has become a standard way to announce a pregnancy. Over 1.5 million public Instagram posts are tagged #genderreveal.

Sharenting raises privacy questions: who owns a child’s image? Can children withdraw publishing permission later?

Sharenting entails handing over children’s data to Facebook as part of the larger realm of surveillance capitalism. A saying that emerged around the same time as Instagram was born still rings true: “When something online is free, you’re not the customer, you’re the product”. We pay for Instagram’s “free” platform with our user data and our children’s data, too, when we share photos of them.

Read more: The real problem with posting about your kids online

5. Seeing through the frame

The apparent “Instagrammability” of a meal, a place, or an experience has seen the rise of numerous visual trends and tropes.

Short-lived Instagram Stories and disappearing Direct Messages add more spaces to express more things without the threat of permanence.

Read more: Friday essay: seeing the news up close, one devastating post at a time

The events of 2020 have shown our ways of seeing on Instagram reveal the possibilities and pitfalls of social media.

In June racial justice activism on #BlackoutTuesday, while extremely popular, also had the effect of swamping the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag with black squares.

Instagram is rife with disinformation and conspiracy theories which hijack the look and feel of authoritive content. The template of popular Instagram content can see familiar aesthetics weaponised to spread misinformation.

Ultimately, the last decade has seen Instagram become one of the main lenses through which we see the world, personally and politically. Users communicate and frame the lives they share with family, friends and the wider world.

Read more: #travelgram: live tourist snaps have turned solo adventures into social occasions

Tama Leaver, Associate Professor in Internet Studies, Curtin University; Crystal Abidin, Senior Research Fellow & ARC DECRA, Internet Studies, Curtin University, Curtin University, and Tim Highfield, Lecturer in Digital Media and Society, University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Facebook is merging Messenger and Instagram chat features. It’s for Zuckerberg’s benefit, not yours

Tama Leaver, Curtin University

Tama Leaver, Curtin University

Facebook Messenger and Instagram’s direct messaging services will be integrated into one system, Facebook has announced.

The merge will allow shared messaging across both platforms, as well as video calls and the use of a range of tools drawn from both platforms. It’s currently being rolled out across countries on an opt-in basis, but hasn’t yet reached Australia.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced plans in March last year to integrate Messenger, Instagram Direct and WhatsApp into a unified messaging experience.

At the crux of this was the goal to administer end-to-end encryption across the whole messaging “ecosystem”.

Ostensibly, this was part of Facebook’s renewed focus on privacy, in the wake of several highly publicised scandals. Most notable was its poor data protection that allowed political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica to steal data from 87 million Facebook accounts and use it to target users with political ads ahead of the 2016 US presidential election.

In a statement released yesterday on the new merge, Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri and Messenger vice president Stan Chudnovsky wrote:

… one out of three people sometimes find it difficult to remember where to find a certain conversation thread. With this update, it will be even easier to stay connected without thinking about which app to use to reach your friends and family.

While that may seem harmless, it’s likely Facebook is actually attempting to make its apps inseparable, ahead of a potential anti-trust lawsuit in the US that may try to see the company sell Instagram and WhatsApp.

Together, with Facebook, 24/7

The Messenger/Instagram Direct merge will extend to features rolled out during the pandemic, such as the “Watch Together” tool for Messenger. As the name suggests, this lets users watch videos together in real time. Now, both Messenger and Instagram users will be able to use it, regardless of which app they’re on.

With the integration, new privacy challenges emerge. Facebook has already acknowledged this. And these challenges will present despite Facebook’s overarching privacy policy applying to every app in its app “family”.

For example, in the new merged messaging ecosystem, a user you previously blocked on Messenger won’t automatically be blocked on Instagram. Thus, the blocked person will be able to once again contact you. This could open doors to a plethora of unexpected online abuse.

Why this is good for Mark Zuckerberg

This first step – and Facebook’s full roadmap for the encrypted integration of WhatsApp, Instagram Direct and Messenger – has three clear outcomes.

Firstly, end-to-end encryption means Facebook will have complete deniability for anything that travels across its messaging tools.

It won’t be able to “see” the messages. While this might be good from a user privacy perspective, it also means anything from bullying, to scams, to illegal drug sales, to paedophilia can’t be policed if it happens via these tools.

This would stop Facebook being blamed for hurtful or illegal uses of its services. As far as moderating the platform goes, Facebook would effectively become “invisible” (not to mention moderation is expensive and complicated).

This is all great news for Mark Zuckerberg, especially as Facebook stares down the barrel of potential anti-trust litigation.

Secondly, once the apps are merged, functionally they will no longer be separate platforms. They will still exist as separate apps with some separate features, but the vast amount of personal data underpinning them will live in one giant, shared database.

Deeper data integration will let Facebook know users more intimately. Moreover, it will be able to leverage this new insight to target users with more advertising and expand further.

Finally, and perhaps most concerning, is that by integrating its apps Facebook could legitimately respond to anti-trust lawsuits by saying it can’t separate Instagram or WhatsApp from the main Facebook platform – because they’re the same thing now.

And if they can’t be separated, there’s no way Facebook could sell Instagram or WhatsApp, even if it wanted to.

100 billion messages a day

The messaging traffic across Facebook’s platforms is vast, with more than 100 billion messages sent daily. And this has only increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With the sheer size of its user database, Facebook continues to either purchase, or squash, its competition. Concerns about the company being a monopoly aren’t without merit.

Researchers and founding Facebook employees have called to have the company split up – and for Instagram and Whatsapp to become separate again.

Just a few months ago, Facebook released its Instagram-housed tool Reels which bears a striking resemblance to TikTok, another social app sweeping the globe.

It seems this is just another example of Facebook trying to use the sheer size of its network to stifle growing competition, aided (perhaps unwittingly) by Donald Trump’s anti-China sentiment.

If competition is important to encouraging innovation and diversity, then the newest development from Facebook discourages both these things. It further entrenches Facebook and its services into the lives of consumers, making it harder to pull away. And this certainly isn’t far from monopolistic behaviour.

![]()

Tama Leaver, Associate Professor in Internet Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Targeted PhD Projects with Scholarship in Internet Studies @ Curtin Uni (to start 2021, applications close 1 Sept 2020)

Opportunities exist to apply for a range of targeted PhD scholarships located within the Internet Studies Discipline at Curtin University. The window of opportunity for these is short, so if you’re interested, please email the contact person listed in the specific project pages as soon as you’re able!

If folks could share these opportunities with current and recent Masters and Honours completions (and those completing this year), we would be grateful!

The projects available:

1. An Ethnography of Influencers and Social Justice Cultures https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4270

2. Analysing Virtual Influencers: Celebrity, Authenticity and Identity on Social Media https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4324

3. Climate Action and the Internet https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4285

4. Digital Disability and Disability Media https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4318

5. Digital Disability Inclusion across the Lifecourse https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4291

6. Digital intimacies and social media https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4286

7. Diversity, Equity and Impact: Exploring the Open Knowledge performance of Universities https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4341

8. Ethical and Sociocultural Impacts of AI/Autonomous Machines as Communicators https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4360

9. Tracking Australia’s Research Response to the COVID Pandemic https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4347

10. The Audio Internet https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/Scholarship/?id=4322

To apply for these project opportunities applicants must submit an email to the contact Project lead listed on the project listing. The email must include their current curriculum vitae, a summary of their research skills and experience and the reason they are interested in this specific project.

The Project Lead will select one preferred applicant for this project and complete a Primary reference on their behalf.

After confirmation from the Project Lead that they will receive a primary reference for this project the applicant must submit an eApplication [https://study.curtin.edu.au/applying/research/#apply] for admission into the applicable HDR course no later than 1st September 2020.

All applicants must send an external referee template [https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/07/RTP2021-Round-2-External-Referee-Report.pdf] to their chosen external reference.

All references are confidential and must be submitted by the referee directly to HDRSCH-applications@curtin.edu.au no later than 1st September 2020.

Scholarship applications submitted without a primary reference or a completed application for admission will be considered incomplete.

For further information on the application process or for more RTP2021 Round 2 scholarship project opportunities visit: https://scholarships.curtin.edu.au/hdr-scholarships-funding/rtp-policy/

Thanks for sharing!

Hybrid Learning and Teaching in Higher Education Pre-Date the Pandemic

One of the most tiresome things about thought pieces on the future of universities pumping out at the moment is the constant presumption that a move to a ‘hybrid’ model of teaching (ie mixing face-to-face and online learning) is something new to everyone. It’s not. As just one example, Internet Studies has taught both face-to-face and online versions of all the units in our major for more than 15 years, both at Curtin University and via Open Universities Australia. Students have *chosen* whichever mode fit their lives best, and students can excel in either.

Also deeply disheartening is the presumption that online teaching is intrinsically less impactful than face-to-face. It’s not. But it takes significant work in curriculum design and learning & teaching modes (yes, even via lectures) to engage online learners. Despite workload models that presume the opposite, teaching units online well takes more time, not less, & it’s rare that just one platform (or ‘learning’ management system) offers enough to encompass that learning. Multiple tools work if there is sufficient support for each. Shifting learning material online at very short notice (because of a pandemic) does not equal online learning, it’s making the best of a bad situation (& colleagues across the sector have done so much more than that), but this isn’t the benchmark against which online learning should be judged.

And despite unprecedented pandemic times, hybrid teaching, online teaching, or even face-to-face teaching that is mindful of the complicated context learners are living in, can clearly be better designed by consulting the mountains of work & research on each of these modes. The pandemic has challenged higher education in profound ways, but we have to do what we do best: build our responses on the research, scholarship & best practice that already exist. We know better than reinventing the wheel in any other context, let’s remember it in this one, too.

Edit: On Facebook Mark Pegrum pointed me to work that frames going online for teaching during the pandemic as ERT, or emergency remote teaching, which is quite compelling terminology. I particularly like this quote:

In contrast to experiences that are planned from the beginning and designed to be online, emergency remote teaching (ERT) is a temporary shift of instructional delivery to an alternate delivery mode due to crisis circumstances.

Approaching Instagram: New Methods and Modes for Examining Visual Social Media

Due to the global pandemic, this year’s International Communication Association conference was held online. This post shares the abstracts and short videos made for our roundtable on ‘Approaching Instagram: New Methods and Modes for Examining Visual Social Media’. Hopefully it might prove useful to those studying Instagram and thinking about methodologies. The participants in this roundtable were Crystal Abidin (Curtin University), Tim Highfield, (University of Sheffield), Tama Leaver, (Curtin University), Anthony McCosker (Swinburne University of Technology), Adam Suess, (Griffith University), Katie Warfield (Kwantlen Polytechnic University) and Alice Witt (Queensland University of Technology).

The Panel Overview

Instagram has more than a billion users, yet despite being owned by Facebook remains a platform that’s vastly more popular with young people, and synonymous with the visual and cultural zeitgeist. However, compared to parent-company Facebook, or competitors such as Twitter, Instagram has been comparatively under-studied and under-researched. Moreover, as Facebook/Instagram have limited researcher access via their APIs, newer research approaches have had to emerge, some drawing on older qualitative approaches to understand and analyse Instagram media and interactions (from images and videos to comments, emoji, hashtags, stories, and more). The eight initial participants in this roundtable, from Australia, Canada, Finland and the United Kingdom, roundtable have pioneered specific research methods for approaching Instagram (across quantitative and qualitative fields), and our intention is to broaden the discussion moving beyond (just) methods to larger questions and ideas of engaging with Instagram as a visual social media icon on which larger social, cultural changes and questions are necessarily explored.

Contributions set the scene for a larger discussion, examining the invisible labour of the ‘Instagram Husband’ as a highly important but almost always hidden figure, particularly mythologized by online influencers. Broader conceptual questions are also raised in terms of how the Instagram platform reconfigures time from 24-hour Stories, looping Boomerangs, to temporality measured relative to when content was posted, with Instagram becoming the centre of its own time and space. Another contributor argues that Instagram users are always creating and fashioning each other, not just themselves, using the liminal figures of the unborn (via ultrasounds) and the recently deceased as case studies where Instagram users are most obviously creating other people in the feeds. Another contributor asks how the world of art is being reconfigured by the aesthetics and practices of being ‘insta-worthy’. Another contribution asks how to move beyond hashtags as the primary method of discovering collections of content. On a different note, the practices of commercial wedding photographers are examined to ask how weddings are being reimagined and renegotiated in an era of social media visuality. Finally, important questions are raised about the content that is not visualized and not allowed on Instagram at all, and how these moderation practices can be mapped against the ‘black box’ of Instagram’s algorithms.

[1] The Instagram Husband / Crystal Abidin, Curtin University

Social media has become a canvas for the commemoration and celebration of milestones. For the highly prolific and commercially viable vocational internet celebrities known as Influencers, coupling up in a relationship is all the more significant, as it impacts their public personae, their market value to sponsors, and their engagement with followers. However, behind-the-scenes of such young women’s pristine posturing are often their romantic partners capturing viable footage from behind-the-camera, in a phenomenon known in popular discourse as “the Instagram husband”. These (often heterosexual male) romantic partners toggle between ‘commodity’ on camera to ‘creator’ off camera. Although the narrative of the Instagram Husband is usually clouded in the notions of sacrificial romance, the unremunerated work is wrought with strain. Between the domesticity of Influencers’ romantic coupling and the publicness of their branded individualism, this chapter considers the labour, tensions, and latent consequences when Influencers intertwine commodify their relationships into viable entities. Through traditional and digital ethnographic research methods and in-depth data collection among Singaporean women Influencers and their (predominantly heterosexual) partners, the chapter contemplates the phenomenon of the Instagram Husband and its impact on visual representations of romantic relationships online.

[2] Examining Instagram time: aesthetics and experiences / Tim Highfield, University of Sheffield

Temporal concerns are critical underpinnings for the presentation and experience of popular social media platforms. Understanding and transforming the temporal is key to the operation of these platforms, becoming a means for platforms to intervene in user activity. On Instagram, temporality plays out in different ways. Ostensibly describing in-the-moment, as-it-happens sharing and live documentation, the Insta- of Instagram has long been complicated by features of the platform and cultural practices and norms which encourage different types of participation and temporal framing. This contribution focuses on how Instagram time is presented and experienced by the platform and its users, from how content appears in non-linear algorithmic feeds to aesthetics that suggest, or explicitly callback to, older technologies and eras. These create temporal contestation as, for example, the implied permanence of the photo stream is contrasted with the ephemerality of Stories, where content usually lasts for only 24 hours, and the trapped seconds-long loops of Boomerangs. This temporal contestation apparent between different features of the platform also plays out in Instagram’s aesthetics, which include retro throwbacks of filters to the explicit visuals of Story filters reminiscent of VHS tape and physical film. Such platformed approaches then raise questions for researchers about Instagram’s temporality, how it is experienced by its users, and how it is repositioned and reframed by the platform’s own architecture, displays, and affordances.

[3] Creating Each Other on Instagram / Tama Leaver, Curtin University

While visual social media platforms such as Instagram are, by definition, about connecting and communication between multiple people, most discussions about Instagram practices presume that accounts, profiles and content are managed by individual users with the agency to make informed choices about their activities. However, Instagram photos and videos more often than not contain other people, and thus the sharing of visual material is often a form of co-creation where the Instagram user is often contributing and shaping another person or group’s online identity (or performance). This contribution outlines some of the larger provocations that occur when examining the way loves ones use Instagram to visualize the very young and the recently deceased. Indeed, even before birth, the sharing of the 12- or 20-week ultrasound photos and gender reveal parties often sees an Instagram identity begin to be shaped by parents before a child is even born. At the other end of life, mourning and funereal media often provide some of the last images and descriptions of a person’s life, something that can prove quite controversial on Instagram. Considering these two examples, this contribution argues that content creation could, and probably should, be considered visual co-creation, and Instagram should be seen as a platform on which users fashion each others identities as much as their own.

[4] Navigating Instagram’s politics of visibility / Anthony McCosker, Swinburne University of Technology

This contribution reflects on several research projects that have had to negotiate Instagram’s depreciated API access, and its increasingly restrictive moderation practices limiting what the company sees as sensitive or harmful content. One project with Australian Red Cross was designed to access and analyse location data for posts engaging with humanitarian activity, in order to generate new insights and information about how to address humanitarian needs particular locations. The other examined users’ engagement with content actively engaged with the depression through hashtag use. Both cases required the adjustment of methods to sustain the research beyond the API restrictions and enable future work to continue to draw insights about the respective research problems. I discuss the development of an inclusive hashtag practices method, data collaborative co-research practices, and visual methods that can account for situational and contextual analysis through a targeted sampling and theory building approach.

[5] Appreciating art through Instagram / Adam Suess, Griffith University

Instagram is an important application for art galleries, museums, and cultural institutions. For arts professionals it is a key tool for promotion, accessibility, participation, and the enhancing of the visitor experience. For arts educators it is an opportunity to influence the number of people who value the arts and seek lifelong learning through the aesthetic experience. Instagram also has pedagogical value in the gallery and is relevant for arts based learning programs. There is limited research about the use of Instagram by visitors to art galleries, museums, and cultural institutions and the role it plays in their social, spatial, and aesthetic experience. This study examined the use of Instagram by visitors to the Gerhard Richter exhibition at the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (14 October 2017 – 4 February 2018). The research project found that the use of Instagram at the gallery engaged visitors in a manner that transcended the physical space, evolving and extending their aesthetic experience. It also found that Instagram acted as a tool of influence shaping the way visitors engaged with art. This finding is significant for arts educators seeking to engage students and the community through Instagram, centered on their experience of art.

[6] Instagram Visuality and The West Coast Wedding / Katie Warfield, Kwantlen Polytechnic University

The intersection of artsy, youthful, beautiful, and playful aesthetics alongside corporate branding have established certain normative modes of visuality on the globally popular social media platform Instagram. Adopting a post-phenomenological lens alongside an intersectional feminist critique of the platform, this paper presents the findings of working with six commercial wedding photographers on the west coast of Canada whose photographs are often shared for clients on social media. Via interviews, photo elicitation, and participant observation, this paper teases apart the multi-stable and manifold socio-technical forces that shape Instagram visuality or the visual sedimented ways of seeing shaped by Instagram and embodied and performed by image producers. This paper shows the habituation of these modes of seeing and argues that Instagram visuality is the result of various and complex intimate conversational negotiations between: discursive visual tropes (e.g. lighting, subject arrangement, and material symbols of union), material technological affordances (in-built filters, product tagging, and the grid layout of user pages), and sedimented discursive-affective “moods” (white material femininity and nature communion) that assemble to shape the normative depictions of west coast weddings.

[7] Probing the black box of content moderation on Instagram: An innovative black box methodology / Alice Witt, Queensland University of Technology

The black box around the internal workings of Instagram makes it difficult for users to trust that their expression through content is moderated, or regulated, in ways that are free from arbitrariness. Against the particular backdrop of allegations that the platform is arbitrarily removing some images depicting women’s bodies, this research develops and applies a new methodology for empirical legal evaluation of content moderation in practice. Specifically, it uses innovative digital methods, in conjunction with content and legal document analyses, to identify how discrete inputs (i.e. images) into Instagram’s moderation processes produce certain outputs (i.e. whether an image is removed or not removed). Overall, across two case studies comprising 5,924 images of female forms in total, the methodology provides a range of useful empirical results. One main finding, for example, is that the odds of removal for an expressly prohibited image depicting a woman’s body is 16.75 times higher than for a man’s body. The results ultimately suggest that concerns around the risk of arbitrariness and bias on Instagram, and, indeed, ongoing distrust of the platform among users, might not be unfounded. However, without greater transparency regarding how Instagram sets, maintains and enforces rules around content, and monitors the performance of its moderators for potential bias, it is difficult to draw explicit conclusions about which party initiates content removal, in what ways and for what reasons. This limitation, among others raised by this methodology, underlines that many vital questions of trust in content moderation on Instagram remain unanswered.