Home » privacy

Category Archives: privacy

Spotlight forum: social media, child influencers and keeping your kids safe online

I was pleased to join Associate Professor Crystal Abidin as panellists on the ABC Perth Radio Spotlight Forum on social media, child influencers and keeping your kids safe online. It was a wide-ranging discussion that really highlights community interest and concern in ensuring our young people have the best access to opportunities online while minimising the risks involved.

You can listen to a recording of the broadcast here.

ABC Perth Spotlight forum: how to protect your privacy in an increasingly tech-driven world

I was pleased to be part of the ABC Perth Radio’s Spotlight Forum on ‘How to Protect Your Privacy in an Increasingly Tech-driven World‘ this morning, hosted by Nadia Mitsopoulos, and also featuring Associate Professor Julia Powles, Kathryn Gledhill-Tucker from Electronic Frontiers Australia and David Yates from Corrs Chambers Westgarth.

I was pleased to be part of the ABC Perth Radio’s Spotlight Forum on ‘How to Protect Your Privacy in an Increasingly Tech-driven World‘ this morning, hosted by Nadia Mitsopoulos, and also featuring Associate Professor Julia Powles, Kathryn Gledhill-Tucker from Electronic Frontiers Australia and David Yates from Corrs Chambers Westgarth.

You can stream the Forum on the ABC website, or download here.

Why the McGowan government will have an uphill battle rebuilding trust in the SafeWA app.

QR code contact-tracing apps are a crucial part of our defence against COVID-19. But their value depends on being widely used, which in turn means people using these apps need to be confident their data won’t be misused.

That’s why this week’s revelation that Western Australian police accessed data gathered using the SafeWA app are a serious concern.

WA Premier Mark McGowan’s government has enjoyed unprecedented public support for its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic thus far. But this incident risks undermining the WA public’s trust in their state’s contact-tracing regime.

While the federal government’s relatively expensive COVIDSafe tracking app — which was designed to work automatically via Bluetooth — has become little more than the butt of jokes, the scanning of QR codes at all kinds of venues has now become second nature to many Australians.

These contact-tracing apps work by logging the locations and times of people’s movements, with the help of unique QR codes at cafes, shops and other public buildings. Individuals scan the code with their phone’s camera, and the app allows this data to be collated across the state.

That data is hugely valuable for contact tracing, but also very personal. Using apps rather than paper-based forms greatly speeds up access to the data when it is needed. And when trying to locate close contacts of a positive COVID-19 case, every minute counts.

But this process necessarily involves the public placing their trust in governments to properly, safely and securely use personal data for the advertised purpose, and nothing else.

Australian governments have a poor track record of protecting personal data, having suffered a range of data breaches over the past few years. At the same time, negative publicity about the handling of personal data by digital and social media companies has highlighted the need for people to be careful about what data they share with apps in general.

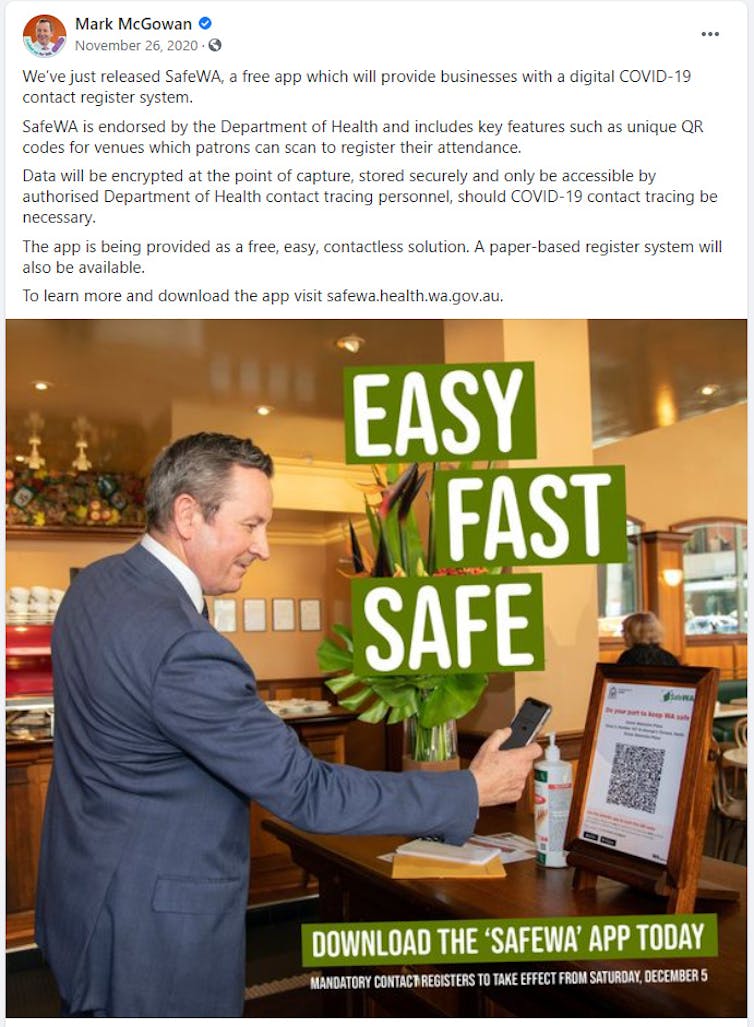

The SafeWA app was downloaded by more than 260,000 people within days of its release, in large part because of widespread trust in the WA government’s strong track record in handling COVID-19. When the app was launched in November last year, McGowan wrote on his Facebook page that the data would “only be accessible by authorised Department of Health contact tracing personnel”.

Mark McGowan’s Facebook Page

In spite of this, it has now emerged that WA Police twice accessed SafeWA data as part of a “high-profile” murder investigation. The fact the WA government knew in April that this data was being accessed, but only informed the public in mid-June, further undermines trust in the way personal data is being managed.

McGowan today publicly criticised the police for not agreeing to stop using SafeWA data. Yet the remit of the police is to pursue any evidence they can legally access, which currently includes data collected by the SafeWA app.

It is the government’s responsibility to protect the public’s privacy via carefully written, iron-clad legislation with no loopholes. Crucially, this legislation needs to be in place before contract-tracing apps are rolled out, not afterwards.

It may well be that the state government held off on publicly disclosing details of the SafeWA data misuse until it had come up with a solution. It has now introduced a bill to prevent SafeWA data being used for any purpose other than contact tracing.

This is a welcome development, and the government will have no trouble passing the bill, given its thumping double majority. Repairing public trust might be a trickier prospect.

Trust is a premium commodity these days, and to have squandered it without adequate initial protections is a significant error.

The SafeWA app provided valuable information that sped up contact tracing in WA during Perth’s outbreak in February. There is every reason to believe that if future cases occur, continued widespread use of the app will make it easier to locate close contacts, speed up targeted testing, and either avoid or limit the need for future lockdowns.

That will depend on the McGowan government swiftly regaining the public’s trust in the app. The new legislation is a big step in that direction, but there’s a lot more work to do. Trust is hard to win, and easy to lose.

Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

When exploiting kids for cash goes wrong on YouTube: the lessons of DaddyOFive

A new piece in The Conversation from Crystal Abidin and me …

Tama Leaver, Curtin University and Crystal Abidin, Curtin University

The US YouTube channel DaddyOFive, which features a husband and wife from Maryland “pranking” their children, has pulled all its videos and issued a public apology amid allegations of child abuse.

The “pranks” would routinely involve the parents fooling their kids into thinking they were in trouble, screaming and swearing at them, only the reveal “it was just a prank” as their children sob on camera.

Despite its removal the content continues to circulate in summary videos from Philip DeFranco and other popular YouTubers who are critiquing the DaddyOFive channel. And you can still find videos of parents pranking their children on other channels around YouTube. But the videos also raise wider issues about children in online media, particularly where the videos make money. With over 760,000 subscribers, it is estimated that DaddyOFive earned between US$200,000-350,000 each year from YouTube advertising revenue.

The rise of influencers

Kid reactions on YouTube are a popular genre, with parents uploading viral videos of their children doing anything from tasting lemons for the first time to engaging in baby speak. Such videos pre-date the internet, with America’s Funniest Home Videos (1989-) and other popular television shows capitalising on “kid moments”.

In the era of mobile devices and networked communication, the ease with which children can be documented and shared online is unprecedented. Every day parents are “sharenting”, archiving and broadcasting images and videos of their children in order to share the experience with friends.

Even with the best intentions, though, one of us (Tama) has argued that photos and videos shared with the best of intentions can inadvertently lead to “intimate surveillance”, where online platforms and corporations use this data to build detailed profiles of children.

YouTube and other social media have seen the rise of influencer commerce, where seemingly ordinary users start featuring products and opinions they’re paid to share. By cultivating personal brands through creating a sense of intimacy with their consumers, these followings can be strong enough for advertisers to invest in their content, usually through advertorials and product placements. While the DaddyOFive channel was clearly for-profit, the distinction between genuine and paid content is often far from clear.

From the womb to celebrity

As with DaddyOFive, these influencers can include entire families, including children whose rights to participate, or choose not to participate, may not always be considered. In some cases, children themselves can be the star, becoming microcelebrities, often produced and promoted by their parents.

South Korean toddler Yebin, for instance, first went viral as a three-year-old in 2014 in a video where her mom was teaching her to avoid strangers. Since then, Yebin and her younger brother have been signed to influencer agencies to manage their content, based on the reach of their channel which has accumulated over 21 million views.

As viral videos become marketable and kid reaction videos become more lucrative, this may well drive more and more elaborate situations and set-ups. Yet, despite their prominence on social media, such children in internet-famous families are not clearly covered by the traditional workplace standards (such as Child Labour Laws and that Coogan Law in the US), which historically protected child stars in mainstream media industries from exploitation.

This is concerning especially since not only are adult influencers featuring their children in advertorials and commercial content, but some are even grooming a new generation of “micro-microcelebrities” whose celebrity and careers begin in the womb.

In the absence of any formal guidelines for the child stars of social media, it is the peers and corporate platforms that are policing the welfare of young children. As prominent YouTube influencers have rallied to denounce the parents behind the DaddyOFive accusing them of child abuse, they have also leveraged their influence to report the parents of DaddyOFive to child protective services. YouTube has also reportedly responded initially by pulling advertising from the channel. YouTubers collectively demonstrating a shared moral position is undoubtedly helpful.

Greater transparency

The question of children, commerce and labour on social media is far from limited to YouTube. Australian PR director Roxy Jacenko has, for example, defended herself against accusations of exploitation after launching and managing a commercial Instagram account for her her young daughter Pixie, who at three-years-old was dubbed the “Princess of Instagram”. And while Jacenko’s choices for Pixie may differ from many other parents, at least as someone in PR she is in a position to make informed and articulated choices about her daughter’s presence on social media.

Already some influencers are assuring audiences that child participation is voluntary, enjoyable, and optional by broadcasting behind-the-scenes footage.

Television, too, is making the most of children on social media. The Ellen DeGeneres Show, for example, regularly mines YouTube for viral videos starring children in order to invite them as guests on the show. Often they are invited to replicate their viral act for a live audience, and the show disseminates these program clips on its corporate YouTube channel, sometimes contracting viral YouTube children with high attention value to star in their own recurring segments on the show.

Ultimately, though, children appearing on television are subject to laws and regulations that attempt to protect their well-being. On for-profit channels on YouTube and other social media platforms there is a little transparency about the role children are playing, the conditions of their labour, and how (and if) they are being compensated financially.

Children may be a one-off in parents’ videos, or the star of the show, but across this spectrum, social media like YouTube need rules to ensure that children’s participation is transparent and their well-being paramount.

Tama Leaver, Associate Professor in Internet Studies, Curtin University and Crystal Abidin, Adjunct Research Fellow at the Centre for Culture and Technology (CCAT), Curtin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Born Digital? Presence, Privacy, and Intimate Surveillance

I’m pleased to note that my chapter ‘Born Digital? Presence, Privacy, and Intimate Surveillance’ is out now in the Re-Orientation: Trans-lingual, Trans-cultural, Trans-media. Studies in narrative, language, identity, and knowledge collection edited by John Hartley and Weiguo Qu for Fudan University Press. The collection is the outcome of the fantastic Culture+8: New Times, New Zones symposium in 2014 which explored cultural synergies between different countries and locations in the +8 timezone which include Perth where we hosted the event, and, of course, China.

I’m pleased to note that my chapter ‘Born Digital? Presence, Privacy, and Intimate Surveillance’ is out now in the Re-Orientation: Trans-lingual, Trans-cultural, Trans-media. Studies in narrative, language, identity, and knowledge collection edited by John Hartley and Weiguo Qu for Fudan University Press. The collection is the outcome of the fantastic Culture+8: New Times, New Zones symposium in 2014 which explored cultural synergies between different countries and locations in the +8 timezone which include Perth where we hosted the event, and, of course, China.

My chapter is a key part of my Ends of Identity project; here I start to think about ‘intimate surveillance’ which is where parents and loved ones digitally document and survey their offspring, from sharing ultrasound photos to tracking newborn feeding and eating patterns. Intimate surveillance is a deliberately contradictory term: something done with the best of intentions but with possibly quite problematic outcomes. Here’s the full abstract:

The moment of birth was once the instant where parents and others first saw their child in the world, but with the advent of various imaging technologies, most notably the ultrasound, the first photos often precede birth (Lupton, 2013). In the past several decades, the question is no longer just when the first images are produced, but who should see them, via which, if any, communication platforms? Should sonograms (the ultrasound photos) be used to announce the impending arrival of a new person in the world? Moreover, while that question is ostensibly quite benign, it does usher in an era where parents and loved ones are, for the first years of life, the ones deciding what, if any, social media presence young people have before they’re in a position to start contributing to those decisions.

This chapter addresses this comparatively new online terrain, postulating the provocative term intimate surveillance, which deliberately turns surveillance on its head, begging the question whether sharing affectionately, and with the best of intentions, can or should be understood as a form of surveillance. Firstly, this chapter will examine the idea of co-creating online identities, touching on some of the standard ways of thinking about identity online, and then starting to look at how these approaches do and do not explicitly address the creation of identity for others, especially parents creating online identities for their kids. I will then review some ideas about surveillance and counter-surveillance with a view to situating these creative parental acts in terms of the kids and others being created. Finally, this chapter will explore several examples of parental monitoring, capturing and sharing of data and media about their children, using various mobile apps, contextualising these activities not with a moral finger-waving, but by surfacing specific questions and literacies which parents may need to develop in order to use these tools mindfully, and ensure decisions made about their children’s’ online presences are purposeful decisions.

The chapter can be read here.

A Methodology for Mapping Instagram Hashtags

Today First Monday published A Methodology for Mapping Instagram Hashtags by Tim Highfield and myself. This methodology paper explains the processes behind the various media we’ve been tracking as part of the Ends of Identity project, although the utility of the methods go far beyond that. Beyond technical questions, we’ve included some important ethical and privacy questions that arose as we started to explore Instagram mapping. Here’s the abstract:

While social media research has provided detailed cumulative analyses of selected social media platforms and content, especially Twitter, newer platforms, apps, and visual content have been less extensively studied so far. This paper proposes a methodology for studying Instagram activity, building on established methods for Twitter research by initially examining hashtags, as common structural features to both platforms. In doing so, we outline methodological challenges to studying Instagram, especially in comparison to Twitter. Finally, we address critical questions around ethics and privacy for social media users and researchers alike, setting out key considerations for future social media research.

The full paper is available at First Monday, fully open access, with a Creative Commons license. As always, your comments, thoughts and feedback are welcome here, or on Twitter.

Captured at Birth? Presence, Privacy and Intimate Surveillance

If you’re interested, Axel Bruns did a great liveblog summary of the paper, and for the truly dedicated there is an mp3 audio copy of the talk. The paper itself is in the process of being written up and should be in full chapter form in a month or so; if you’d like to look over a full draft once it’s written up, just let me know.

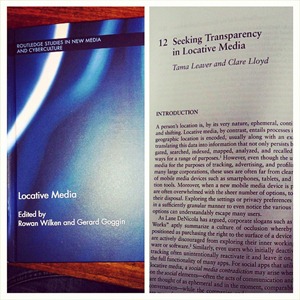

New chapter: Seeking Transparency in Locative Media

The newly-released edited collection Locative Media by Rowan Wilken and Gerard Goggin features a chapter from Clare Lloyd and me looking at issues of privacy and transparency relating to the data generated, stored and analysed when using mobile and locative-based services. Here’s the abstract:

The newly-released edited collection Locative Media by Rowan Wilken and Gerard Goggin features a chapter from Clare Lloyd and me looking at issues of privacy and transparency relating to the data generated, stored and analysed when using mobile and locative-based services. Here’s the abstract:

A person’s location is, by its very nature, ephemeral, continually changing and shifting. Locative media, by contrast, is created when a device encodes a users’ geographic location, and usually the exact time as well, translating this data into information that not only persists, but can be aggregated, searched, indexed, mapped, analysed and recalled in a variety of ways for a range of purposes However, while the utility of locative media for the purposes of tracking, advertising and profiling is obvious to many large corporations, these uses are far from transparent for many users of mobile media devices such as smartphones, tablets and satellite navigation tools. Moreover, when a new mobile media device is purchased, users are often overwhelmed with the sheer number of options, tools and apps at their disposal. Often, exploring the settings or privacy preferences of a new device in a sufficiently granular manner to even notice the various location-related options simply escapes many new users. Similarly, even those who deactivate geolocation tracking initially often unintentionally reactivate it, and leave it on, in order to use the full functionality of many apps. A significant challenge has thus arisen: how can users be made aware of the potential existence and persistence of their own locative media? This chapter examines a number of tools and approaches which are designed to inform everyday users of the uses, and potential abuses, or locative media; PleaseRobMe, I Can Stalk U, iPhone Tracker and the aptly named Creepy. These awareness-raising tools make visible the operation of certain elements of locative media, such as revealing the existence of geographic coordinates in cameraphone photographs, and making explicit possible misuses of a visible locative media trail. All four are designed as pedagogical tools, aiming to make users aware of the tools they are already using. In an era where locative media devices are easy to use but their ease occludes extremely complex data generation and potential tracking, this chapter argues that these tools are part of a significant step forward in developing public awareness of locative media, and related privacy issues.

A version of the chapter is available at Academia.edu (and just for fun, the book has a 2015 publication date, so at the moment, it’s *from the future*!)

Mapping the Ends of Identity on Instagram

At last week’s Australian and New Zealand Communication Association (ANZCA) conference at Swinburne University in Melbourne I gave a new paper by myself and Tim Highfield entitled ‘Mapping the Ends of Identity on Instagram’. The slides, abstract, and audio recording of the talk are below:

While many studies explore the way that individuals represent themselves online, a less studied but equally important question is the way that individuals who cannot represent themselves are portrayed. This paper outlines an investigation into some of those individuals, exploring the ends of identity – birth and death – and the way the very young and deceased are portrayed via the popular mobile photo sharing app and platform Instagram. In order to explore visual representations of birth and death on Instagram, photos with four specific tags were tracked: #birth, #ultrasound, #funeral and #RIP. The data gathered included quantitative and qualitative material. On the quantitative front, metadata was aggregated about each photo posted for three months using the four target tags. This includes metadata such as the date taken, place taken, number of likes, number of comments, what tags were used, and what descriptions were given to the photographs. The quantitative data gives also gives an overall picture of the frequency and volume of the tags used. To give a more detailed understanding of the photos themselves, on one day of each month tracked, all of the photographs on Instagram using the four tags were downloaded and coded, giving a much clearer representative sampling of exactly how each tag is used, the sort of photos shared, and allowed a level of filtering. For example, the #ultrasound hashtag includes a range of images, not just prenatal ultrasounds, including both current images (taken and shared at that moment), historical images, collages, and even ultrasound humour (for example, prenatal ultrasound images with including a photoshopped inclusion of a cash, or a cigarette, joking about the what the future might hold). This paper will outline the methods developed for tracking Instagram photos via tags, it will then present a quantitative overview of the uses and frequency of the four hashtags tracked, give a qualitative overview of the #ultrasound and #RIP tags, and conclude with some general extrapolations about the way that birth and death are visually represented online in the era of mobile media.

And the audio recording of the talk is available on Soundcloud for those who are willing to brave the mediocre quality and variable volume (because I can’t talk without pacing about, it seems!).

Is Facebook finally taking anonymity seriously?

Having some form of anonymity online offers many people a kind of freedom. Whether it’s used for exposing corruption or just experimenting socially online it provides a way for the content (but not its author) to be seen.

But this freedom can also easily be abused by those who use anonymity to troll, abuse or harass others, which is why Facebook has previously been opposed to “anonymity on the internet”.

So in announcing that it will allow users to log in to apps anonymously, is Facebook is taking anonymity seriously?

Real identities on Facebook

CEO Mark Zuckerberg has been committed to Facebook as a site for users to have a single real identity since its beginning a decade ago as a platform to connect college students. Today, Facebook’s core business is still about connecting people with those they already know.

But there have been concerns about what personal information is revealed when people use any third-party apps on Facebook.

So this latest announcement aims to address any reluctance some users may have to sign in to third-party apps. Users will soon be able to log in to them without revealing any of their wealth of personal information.

That does not mean they will be anonymous to Facebook – the social media site will still track user activity.

It might seem like the beginning of a shift away from singular, fixed identities, but tweaking privacy settings hardly indicates that Facebook is embracing anonymity. It’s a long way from changing how third-party apps are approached to changing Facebook’s entire real-name culture.

Facebook still insists that “users provide their real names and information”, which it describes as an ongoing “commitment” users make to the platform.

Changing the Facebook experience?

Having the option to log in to third-party apps anonymously does not necessarily mean Facebook users will actually use it. Effective use of Facebook’s privacy settings depends on user knowledge and motivation, and not all users opt in.

A recent Pew Research Center report reveals that the most common strategy people use to be less visible online is to clear their cookies and browser history.

Only 14% of those interviewed said they had used a service to browse the internet anonymously. So, for most Facebook users, their experience won’t change.

Facebook login on other apps and websites

Facebook offers users the ability to use their authenticated Facebook identity to log in to third-party web services and mobile apps. At its simplest and most appealing level, this alleviates the need for users to fill in all their details when signing up for a new app. Instead they can just click the “Log in with Facebook” button.

For online corporations whose businesses depend on building detailed user profiles to attract advertisers, authentication is a real boon. It means they know exactly what apps people are using and when they log in to them.

Automated data flows can often push information back into the authenticating service (such as the music someone is playing on Spotify turning up in their Facebook newsfeed).

While having one account to log in to a range of apps and services is certainly handy, this convenience means it’s almost impossible to tell what information is being shared.

Is Facebook just sharing your email address and full name, or is it providing your date of birth, most recent location, hometown, a full list of friends and so forth? Understandably, this again raises privacy concerns for many people.

How anonymous login works

To address these concerns, Facebook is testing anonymous login as well as a more granular approach to authentication. (It’s worth noting, neither of these changes have been made available to users yet.)

Given the long history of privacy missteps by Facebook, the new login appears to be a step forward. Users will be told what information an app is requesting, and have the option of selectively deciding which of those items Facebook should actually provide.

Facebook will also ask users whether they want to allow the app to post information to Facebook on their behalf. Significantly, this now places the onus on users to manage the way Facebook shares their information on their behalf.

In describing anonymous login, Facebook explains that:

Sometimes people want to try out apps, but they’re not ready to share any information about themselves.

It’s certainly useful to try out apps without having to fill in and establish a full profile, but very few apps can actually operate without some sort of persistent user identity.

The implication is once a user has tested an app, to use its full functionality they’ll have to set up a profile, probably by allowing Facebook to share some of their data with the app or service.

Taking on the competition

The value of identity and anonymity are both central to the current social media war to gain user attention and loyalty.

Facebook’s anonymous login might cynically be seen as an attempt to court users who have flocked to Snapchat, an app which has anonymity built into its design from the outset.

Snapchat’s creators famously turned down a US$3 billion buyout bid from Facebook. Last week it also revealed part of its competitive plan, an updated version of Snapchat that offers seamless real-time video and text chat.

By default, these conversations disappear as soon as they’ve happened, but users can select important items to hold on to.

Whether competing with Snapchat, or any number of other social media services, Facebook will have to continue to consider the way identity and anonymity are valued by users. At the moment its flirting with anonymity is tokenistic at best.

![]()

Tama Leaver receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC).

Emily van der Nagel does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.