Home » Curtin

Category Archives: Curtin

The Future Of Children’s Online Privacy

I was delighted to join Dr Anna Bunn, Deputy Head of Curtin Law School, and the Future Of team for a podcast interview all about Children’s Online Privacy.

The half hour podcast is online here in various formats, including shownotes, or embedded in this post:

We discuss:

What’s the impact of parents sharing content of their children online? And what rights do children have in this space?

In this episode, Jessica is joined by Dr Anna Bunn, Deputy Head of Curtin Law School and Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies at Curtin University to discuss “sharenting” – the growing practice of parents sharing images and data of their children online. The three examine the social, legal and developmental impacts a life-long digital footprint can have on a child.

- What is the impact of sharing child-related content on our kids? [04:08]

- What type of tools and legal protections would you like to see in the future to protect children? [16:30]

- At what age can a child give consent to share content [18:25]

- What about the right to be forgotten [21:11]

- What’s best practice for sharing child-related content online? [26:01]

Web’s inventor says news media bargaining code could break the internet. He’s right — but there’s a fix

Tama Leaver, Curtin University

The inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, has raised concerns that Australia’s proposed News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code could fundamentally break the internet as we know it.

His concerns are valid. However, they could be addressed through minor changes to the proposed code.

How could the code break the web?

The news media bargaining code aims to level the playing field between media companies and online giants. It would do this by forcing Facebook and Google to pay Australian news businesses for content linked to, or featured, on their platforms.

In a submission to the Senate inquiry about the code, Berners-Lee wrote:

Specifically, I am concerned that the Code risks breaching a fundamental principle of the web by requiring payment for linking between certain content online. […] The ability to link freely — meaning without limitations regarding the content of the linked site and without monetary fees — is fundamental to how the web operates.

Currently, one of the most basic underlying principles of the web is there is no cost involved in creating a hypertext link (or simply a “link”) to any other page or object online.

When Berners-Lee first devised the World Wide Web in 1989, he effectively gave away the idea and associated software for free, to ensure nobody would or could charge for using its protocols.

He argues the news media bargaining code could set a legal precedent allowing someone to charge for linking, which would let the genie out of the bottle — and plenty more attempts to charge for linking to content would appear.

If the precedent were set that people could be charged for simply linking to content online, it’s possible the underlying principle of linking would be disrupted.

As a result, there would likely be many attempts by both legitimate companies and scammers to charge users for what is currently free.

While supporting the “right of publishers and content creators to be properly rewarded for their work”, Berners-Lee asks the code be amended to maintain the principle of allowing free linking between content.

Google and Facebook don’t just link to content

Part of the issue here is Google and Facebook don’t just collect a list of interesting links to news content. Rather the way they find, sort, curate and present news content adds value for their users.

They don’t just link to news content, they reframe it. It is often in that reframing that advertisements appear, and this is where these platforms make money.

For example, this link will take you to the original 1989 proposal for the World Wide Web. Right now, anyone can create such a link to any other page or object on the web, without having to pay anyone else.

But what Facebook and Google do in curating news content is fundamentally different. They create compelling previews, usually by offering the headline of a news article, sometimes the first few lines, and often the first image extracted.

For instance, here is a preview Google generates when someone searches for Tim Berners-Lee’s Web proposal:

Evidently, what Google returns is more of a media-rich, detailed preview than a simple link. For Google’s users, this is a much more meaningful preview of the content and better enables them to decide whether they’ll click through to see more.

Another huge challenge for media businesses is that increasing numbers of users are taking headlines and previews at face value, without necessarily reading the article.

This can obviously decrease revenue for news providers, as well as perpetuate misinformation. Indeed, it’s one of the reasons Twitter began asking users to actually read content before retweeting it.

A fairly compelling argument, then, is that Google and Facebook add value for consumers via the reframing, curating and previewing of content — not just by linking to it.

Can the code be fixed?

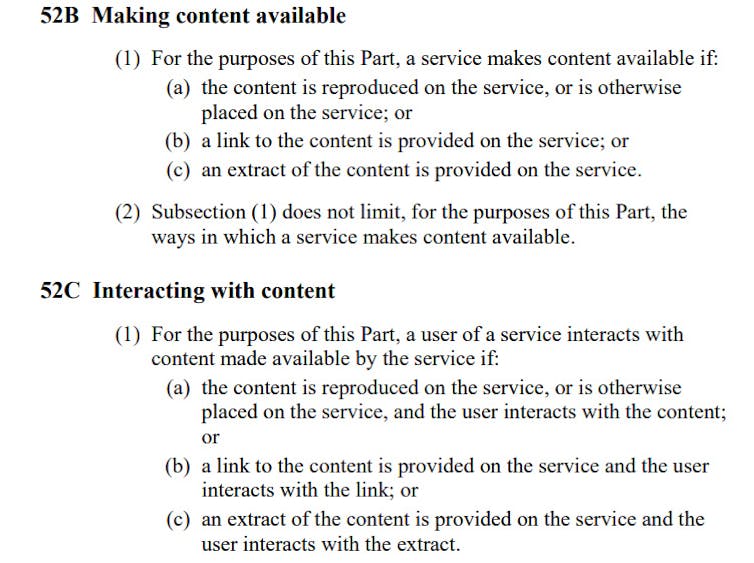

Currently in the code, the section concerning how platforms are “Making content available” lists three ways content is shared:

- content is reproduced on the service

- content is linked to

- an extract or preview is made available.

Similar terms are used to detail how users might interact with content.

Australian Government

If we accept most of the additional value platforms provide to their users is in curating and providing previews of content, then deleting the second element (which just specifies linking to content) would fix Berners-Lee’s concerns.

It would ensure the use of links alone can’t be monetised, as has always been true on the web. Platforms would still need to pay when they present users with extracts or previews of articles, but not when they only link to it.

Since basic links are not the bread and butter of big platforms, this change wouldn’t fundamentally alter the purpose or principle of creating a more level playing field for news businesses and platforms.

In its current form, the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code could put the underlying principles of the world wide web in jeopardy. Tim Berners-Lee is right to raise this point.

But a relatively small tweak to the code would prevent this, It would allow us to focus more on where big platforms actually provide value for users, and where the clearest justification lies in asking them to pay for news content.

For transparency, it should be noted The Conversation has also made a submission to the Senate inquiry regarding the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code.![]()

Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Workshops past & coming soon…

So 2016 seems to be all about the workshops and Summer School so far!

Just finished:

- On 1 February, my first day back from leave, I presented “Developing a Scholarly Web Presence and Using Social Media for Research Networking” at the Perth Research Bazaar (ResBaz) held at Murdoch University (slides available here). The talk was vey well received, with some great questions. Also, kudos to the organizers for the ease of parking!

- Last week I had the great pleasure in facilitating several workshops with my collaborator Tim Highfield, updating our “Instagrammatics: Analysing Visual Social Media Workshop” (slides here) for the 2016 CCI Summer School on Digital Methods hosted by the fabulous folks at the QUT Digital Media Research Centre. This was a fabulous event, with participants from across the world, all exploring the nuances of Digital Media methods and research. Tim and I learnt just as much from our participants as we brought to the table, which makes events like this so very rewarding. And there may have been one or two moments of levity, too!

Coming Up:

- On March 8th I’ll be giving a talk Introducing TrISMA – Tracking Infrastructure for Social Media Analytics with Alkim Ozaygen. This will be held in the new Internet of Everything Innovation Centre at Curtin and is hosted by the Curtin Institute for Computation (CIC).

- On March 30th, I’ll be facilitating a workshop at ECU Mouth Lawley (and livestreamed elsewhere, I believe) on “Promoting Your Research Online and Social Media Awareness”. This is tailored for ECU’s postgradaute students, but is open for anyone else to attend.

- Finally, for now, on May 2 I’ll be the first presenter at the Socialising Your Research – Postgrad and ECR Workshop @ UWA (flyer below). This event is open at anyone interested in WA, but RSVPs are needed (see the flyer for details).

Strategies for Developing a Scholarly Web Presence During a Higher Degree

As part of the Curtin Humanities Research Skills and Careers Workshops 2015 I recently facilitated a workshop entitled Strategies for Developing a Scholarly Web Presence During a Higher Degree. As the workshop received a very positive response and addressed a number of strategies and issues that participants had not addressed previously, I thought I’d share the slides here in case they’re of use to others.

For more context regarding scholarly use of social media in particular, it’s worth checking out Deborah Lupton’s 2014 report ‘Feeling Better Connected’: Academics’ Use of Social Media.

Is Facebook finally taking anonymity seriously?

By Tama Leaver, Curtin University and Emily van der Nagel, Swinburne University of Technology

Having some form of anonymity online offers many people a kind of freedom. Whether it’s used for exposing corruption or just experimenting socially online it provides a way for the content (but not its author) to be seen.

But this freedom can also easily be abused by those who use anonymity to troll, abuse or harass others, which is why Facebook has previously been opposed to “anonymity on the internet”.

So in announcing that it will allow users to log in to apps anonymously, is Facebook is taking anonymity seriously?

Real identities on Facebook

CEO Mark Zuckerberg has been committed to Facebook as a site for users to have a single real identity since its beginning a decade ago as a platform to connect college students. Today, Facebook’s core business is still about connecting people with those they already know.

But there have been concerns about what personal information is revealed when people use any third-party apps on Facebook.

So this latest announcement aims to address any reluctance some users may have to sign in to third-party apps. Users will soon be able to log in to them without revealing any of their wealth of personal information.

That does not mean they will be anonymous to Facebook – the social media site will still track user activity.

It might seem like the beginning of a shift away from singular, fixed identities, but tweaking privacy settings hardly indicates that Facebook is embracing anonymity. It’s a long way from changing how third-party apps are approached to changing Facebook’s entire real-name culture.

Facebook still insists that “users provide their real names and information”, which it describes as an ongoing “commitment” users make to the platform.

Changing the Facebook experience?

Having the option to log in to third-party apps anonymously does not necessarily mean Facebook users will actually use it. Effective use of Facebook’s privacy settings depends on user knowledge and motivation, and not all users opt in.

A recent Pew Research Center report reveals that the most common strategy people use to be less visible online is to clear their cookies and browser history.

Only 14% of those interviewed said they had used a service to browse the internet anonymously. So, for most Facebook users, their experience won’t change.

Facebook login on other apps and websites

Facebook offers users the ability to use their authenticated Facebook identity to log in to third-party web services and mobile apps. At its simplest and most appealing level, this alleviates the need for users to fill in all their details when signing up for a new app. Instead they can just click the “Log in with Facebook” button.

For online corporations whose businesses depend on building detailed user profiles to attract advertisers, authentication is a real boon. It means they know exactly what apps people are using and when they log in to them.

Automated data flows can often push information back into the authenticating service (such as the music someone is playing on Spotify turning up in their Facebook newsfeed).

While having one account to log in to a range of apps and services is certainly handy, this convenience means it’s almost impossible to tell what information is being shared.

Is Facebook just sharing your email address and full name, or is it providing your date of birth, most recent location, hometown, a full list of friends and so forth? Understandably, this again raises privacy concerns for many people.

How anonymous login works

To address these concerns, Facebook is testing anonymous login as well as a more granular approach to authentication. (It’s worth noting, neither of these changes have been made available to users yet.)

Given the long history of privacy missteps by Facebook, the new login appears to be a step forward. Users will be told what information an app is requesting, and have the option of selectively deciding which of those items Facebook should actually provide.

Facebook will also ask users whether they want to allow the app to post information to Facebook on their behalf. Significantly, this now places the onus on users to manage the way Facebook shares their information on their behalf.

In describing anonymous login, Facebook explains that:

Sometimes people want to try out apps, but they’re not ready to share any information about themselves.

It’s certainly useful to try out apps without having to fill in and establish a full profile, but very few apps can actually operate without some sort of persistent user identity.

The implication is once a user has tested an app, to use its full functionality they’ll have to set up a profile, probably by allowing Facebook to share some of their data with the app or service.

Taking on the competition

The value of identity and anonymity are both central to the current social media war to gain user attention and loyalty.

Facebook’s anonymous login might cynically be seen as an attempt to court users who have flocked to Snapchat, an app which has anonymity built into its design from the outset.

Snapchat’s creators famously turned down a US$3 billion buyout bid from Facebook. Last week it also revealed part of its competitive plan, an updated version of Snapchat that offers seamless real-time video and text chat.

By default, these conversations disappear as soon as they’ve happened, but users can select important items to hold on to.

Whether competing with Snapchat, or any number of other social media services, Facebook will have to continue to consider the way identity and anonymity are valued by users. At the moment its flirting with anonymity is tokenistic at best.

![]()

Tama Leaver receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC).

Emily van der Nagel does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

A Methodology for Mapping Instagram Hashtags

At this week’s Digital Humanities Australasia 2014 conference in Perth, Tim Highfield and I presented the first paper from a new project looking a visual social media, with a particular focus on Instagram. The slides and abstract are below (sadly with Slideshare discontinuing screencasts, I’m not sure if I’ll be adding audio to presentations again):

Social media platforms for content-sharing, information diffusion, and publishing thoughts and opinions have been the subject of a wide range of studies examining the formation of different publics, politics and media to health and crisis communication. For various reasons, some platforms are more widely-represented in research to date than others, particularly when examining large-scale activity captured through automated processes, or datasets reflecting the wider trend towards ‘big data’. Facebook, for instance, as a closed platform with different privacy settings available for its users, has not been subject to the same extensive quantitative and mixed-methods studies as other social media, such as Twitter. Indeed, Twitter serves as a leading example for the creation of methods for studying social media activity across myriad contexts: the strict character limit for tweets and the common functions of hashtags, replies, and retweets, as well as the more public nature of posting on Twitter, mean that the same processes can be used to track and analyse data collected through the Twitter API, despite covering very different subjects, languages, and contexts (see, for instance, Bruns, Burgess, Crawford, & Shaw, 2012; Moe & Larsson, 2013; Papacharissi & de Fatima Oliveira, 2012)

Building on the research carried out into Twitter, this paper outlines the development of a project which uses similar methods to study uses and activity on through the image-sharing platform Instagram. While the content of the two social media platforms is dissimilar – short textual comments versus images and video – there are significant architectural parallels which encourage the extension of analytical methods from one platform to another. The importance of tagging on Instagram, for instance, has conceptual and practical links to the hashtags employed on Twitter (and other social media platforms), with tags serving as markers for the main subjects, ideas, events, locations, or emotions featured in tweets and images alike. The Instagram API allows queries around user-specified tags, providing extensive information about relevant images and videos, similar to the results provided by the Twitter API for searches around particular hashtags or keywords. For Instagram, though, the information provided is more detailed than with Twitter, allowing the analysis of collected data to incorporate several different dimensions; for example, the information about the tagged images returned through the Instagram API will allow us to examine patterns of use around publishing activity (time of day, day of the week), types of content (image or video), filters used, and locations specified around these particular terms. More complex data also leads to more complex issues; for example, as Instagram photos can accrue comments over a long period, just capturing metadata for an image when it is first available may lack the full context information and scheduled revisiting of images may be necessary to capture the conversation and impact of an Instagram photo in terms of comments, likes and so forth.

This is an exploratory study, developing and introducing methods to track and analyse Instagram data; it builds upon the methods, tools, and scripts used by Bruns and Burgess (2010, 2011) in their large-scale analysis of Twitter datasets. These processes allow for the filtering of the collected data based on time and keywords, and for additional analytics around time intervals and overall user contributions. Such tools allow us to identify quantitative patterns within the captured, large-scale datasets, which are then supported by qualitative examinations of filtered datasets.

References

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2010). Mapping Online Publics. Retrieved from http://mappingonlinepublics.net

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2011, June 22). Gawk scripts for Twitter processing. Mapping Online Publics. Retrieved from http://mappingonlinepublics.net/resources/

Bruns, A., Burgess, J., Crawford, K., & Shaw, F. (2012). #qldfloods and @ QPSMedia: Crisis Communication on Twitter in the 2011 South East Queensland Floods. Brisbane. Retrieved from http://cci.edu.au/floodsreport.pdf

Moe, H., & Larsson, A. O. (2013). Untangling a Complex Media System. Information, Communication & Society, 16(5), 775–794. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2013.783607

Papacharissi, Z., & de Fatima Oliveira, M. (2012). Affective News and Networked Publics: The Rhythms of News Storytelling on #Egypt. Journal of Communication, 62, 266–282. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01630.x

Angry Birds as a Social Network Market

Earlier today my colleague Michele Willson and I ran the ANZCA PreConference Social, Casual, Mobile: Changing Games which went really well, bringing together 17 games scholars from Australia and Canada, including a fantastic keynote by Mia Consalvo and plenary by John Banks.

I also had the opportunity to present today, and the slides and audio from my talk are below:

And here’s the abstract if you’re interested:

The hugely successful franchise Angry Birds by Finnish company Rovio is synonymous with the new and growing market of app-based games played on smartphones and tablets. These are often referred to as ‘casual games’, highlighting their design which rewards short bursts of play, usually on mobile media devices, rather than the sustained attention and dedicated hardware required for larger PC or console games. Significantly, there is enormous competition within the mobile games, while the usually very low cost (free, or just one or two dollars) makes a huge ranges of choices available to the average consumer. Moreover, these choices are usually framed by just one standardised interface, such as the Google Play store for Android powered devices, or the Apple App store for iOS devices. Within this plethora of options, I will argue that in addition to being well designed and enjoyable to play, successful mobile games are consciously situated within a social network market.

The concepts of ‘social network markets’ reframes the creative industries not so much as the generators of intellectual property outputs, but as complex markets in which the circulation and value of media is as much about taste, recommendations and other networked social affordances (Potts, Cunningham, Hartley, & Ormerod, 2008). For mobile games, one of the most effective methods of reaching potential players, then, is through the social attentions and activity of other players. Rovio have been very deliberate in the wide-spread engagement with players across a range of social media platforms, promoting competitive play via Twitter and Facebook, highlighting user engagement such as showcasing Angry Birds themed cakes, and generally promoting fan engagement on many levels, encouraging the ‘spreadability’ of Angry Birds amongst social networks (Jenkins, Ford, & Green, 2013). In line with recognising the importance of engagement with the franchise, Rovio have also taken a very positive approach of unauthorised merchandising and knock-offs, especially in China and South-East Asia. In line with Montgomery and Potts’ (2008) argument that a weaker intellectual property approach will foster a more innovative creative industries in China, rather than attempting to litigate of lock down unauthorised material, Rovio have stated they see this as building awareness of Angry Birds and are working to harness this new, socially-driven market (Dredge, 2012). As Rovio now license everything from Angry Birds plush toys to theme parks, social network markets can be perpetuated even by unauthorised material, which builds awareness and interest in the official games and merchandising in the long run. Far from a standalone example, this paper argues that not only is Rovio consciously situating Angry Birds within a social network market model, but that such a model can drive other mobile games success in the future.

References

Dredge, S. (2012, January 30). Angry Birds boss: “Piracy may not be a bad thing: it can get us more business.” The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/appsblog/2012/jan/30/angry-birds-music-midem

Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York and London: New York University Press.

Montgomery, L., & Potts, J. (2008). Does weaker copyright mean stronger creative industries? Some lessons from China. Creative Industries Journal, 1(3), 245–261. doi:10.1386/cij.1.3.245/1

Potts, J., Cunningham, S., Hartley, J., & Ormerod, P. (2008). Social network markets: a new definition of the creative industries. Journal of Cultural Economics, 32(3), 167–185. doi:10.1007/s10824-008-9066-y

National Teaching Award!

At an amazing ceremony and dinner at the National Gallery in Canberra tonight I was surprised, flattered and delighted to receive an Australian Award for University Teaching in the Humanities and Arts. This is a huge honour, and I’m extremely grateful to have my approaches to learning and teaching acknowledged in this manner. That said, I’m incredibly conscious that no one teaches in a vacuum, and in Internet Communications I am but one cog in a very complex and well-maintained machine, so this award is at least as much testimony to all of our team at Curtin University as it is to me.

Most importantly, though, I wanted to publicly thank the students who offered their thoughts and feedback about my teaching. We live in an era where students get asked to fill in an awfully large number of feedback forms, surveys and evaluations, so adding even one more thing to that pile is a big ask. So, THANK YOU to all of my students, current and past, whose kind words led to this award.

I’d also like to think that this award is a reminder that despite the huge media attention being paid to MOOCs and so forth, quality online education has been available and refined over more than a decade, and our Internet Communications program is one such example. I truly hope that as this next generation of online learning matures, close attention will be paid to successful examples already available! Successful learning and teaching is, after all, built on understanding the successes and failures of the past.

Who Do You Think You Are 2.0?

At today’s first day of the Perth CCI Symposium I presented the next section of my ongoing Ends of Identity research project as part of the Cultural Science session. I’ve attempted to use the BBC TV series Who Do You Think You Are? to explore how social media both before, during and after our lives shapes, frames and reframes who ‘we’ are in various ways.

As always, comments, questions and criticism are most welcome! ![]()

Facebook, Student Engagement, and the ‘Uni Coffee Shop’ Group

Here are the final slides and audio from Internet Research 13 in MediaCityUK, Salford. My last paper ‘Facebook, Student Engagement, and the ‘Uni Coffee Shop’ Group’ was presented as part of a panel about Facebook and Higher Education which also featured work by my collegues Mike Kent, Kate Raynes-Golide and Clare Lloyd.

The abstract:

While the curriculum, lecturers and tutors teaching Internet Communications via Open Universities Australia (OUA) have been engaging with students for several years using Twitter (see Leaver, 2012), in the past Facebook had been largely left alone since this was viewed as a more casual space where students might interact with each other, but not with teaching staff. However, in the last two years, more and more students have created groups to use Facebook as a discussion space about their units, often attracting a significant proportion of students from that unit. While these groups are important, of even more interest is the establishment of the group called the ‘Uni Coffee Shop’. Unlike the unit-specific groups, the Coffee Shop group, established by two Internet Communications students but open to anyone studying online via OUA, affords group support, social connectivity and a persistent online space for conversation which does not disappear or grow stagnant when students complete a specific unit.

This paper will outline an investigation into the effectiveness of the Uni Coffee Shop group as a student-created space for engagement and informal learning. Three modes of inquiry were used: a textual analysis of the common topics of discussion in the group over several months; a quantitative survey of members of the Coffee Shop group; and several follow-up qualitative interviews with Coffee Shop group members, including the two students who administer the group. In addition, the paper includes the perspectives of teaching staff who have been invited to join the group by students and who, at times, answer specific questions and engage with students in a less formal manner. In detailing the results of these mechanisms, this paper will argue that fostering student-run spaces of engagement using Facebook can be a very effective means to create spaces of engagement and informal learning (Krause & Coates, 2008; Greenhow & Robelia, 2009); the support students give each other can persist over the length of an entire degree; and teaching staff engaging with students in their space, often on their terms, can create a better rapport and a stronger sense of connectivity over the length of a student’s entire degree (and potentially beyond). A student-run Facebook group also provide a space where teaching staff and students can interact using the affordances of Facebook without staff having to explicitly ‘friend’ students (something many staff are reluctant to do for a range of reasons).

References

Greenhow, C., & Robelia, B. (2009). Informal learning and identity formation in online social networks. Learning, Media and Technology, 34(2), 119 – 140.

Krause, K., & Coates, H. (2008). Students’ engagement in first‐year university. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5), 493-505. doi:10.1080/02602930701698892

Leaver, T. (2012). Twittering informal learning and student engagement in first-year units. In A. Herrington, J. Schrape, & K. Singh (Eds.), Engaging students with learning technologies (pp. 97–110). Perth, Australia: Curtin University. Retrieved from http://espace.library.curtin.edu.au/R?func=dbin-jump-full&local_base=gen01-era02&object_id=187303