Talking about Coronavirus/covid19 and misinformation online

I spoke with Hilary Smale on ABC Perth Radio’s Focus program this morning about Coronavirus/ COVID19 and the challenges of misinformation (or what’s now called an ‘infodemic’ on social media). You can hear the program here: https://www.abc.net.au/radio/perth/programs/focus/corona-reset/12046430 (I’m on at about 29.30 in the recording).

My main advice to all social media users remains: slowing down and checking in with known credible sources *before sharing* is vital in stopping misinformation spreading rapidly online (even that sharing is done with the best of intentions).

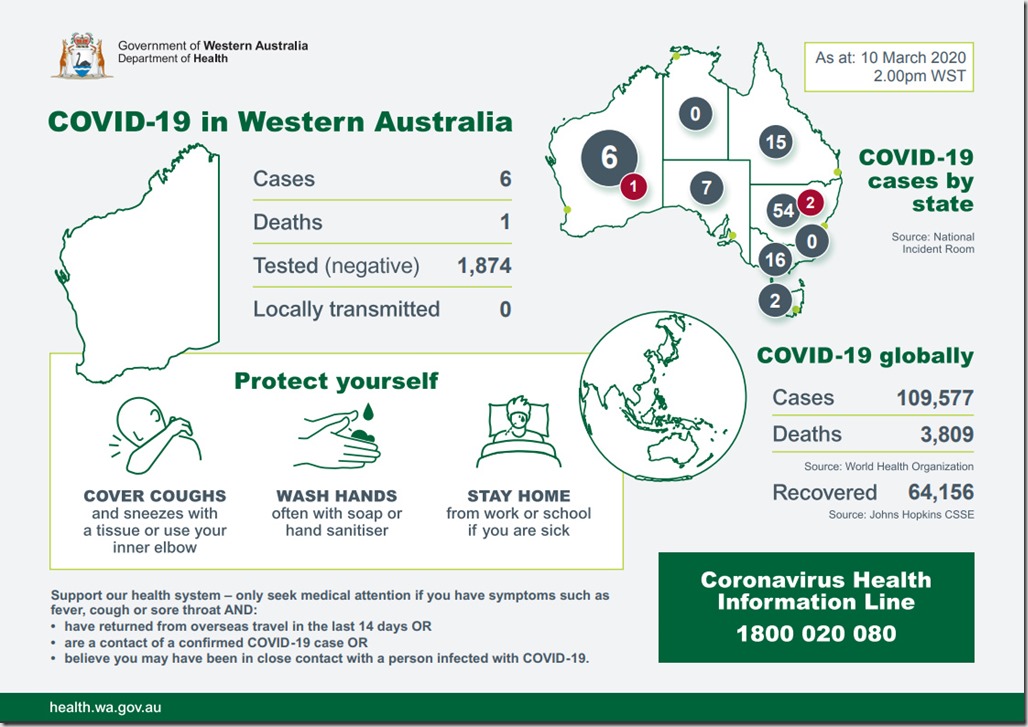

Locally, the most reliable source remains the WA Health Department, and their specific page with up-to-date COVID19 information, here: https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/Articles/A_E/Coronavirus

Their official daily snapshot comes in a particularly shareable visual form:

[Example of WA Health Department COVID-19 Infographic for 10 March 2020.]

Nationally, the Australian Government’s Department of Health website remains the best national resource for reliable information (despite, to be fair, a really unfriendly website): https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov.

Finally, the World Health Organization (WHO) not only provides a reliable global overview but also, vitally, addresses many online rumours about COVID-19 and answers with known facts! https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters

[Examples of World Health Organisation Mythbusting Images, 10 March 2020.]

Life and Death on Social Media Podcast

As part of Curtin University’s new The Future Of podcast series, I was recently interviewed about my ongoing research into pre-birth and infancy at one end, and digital death at the other, in relation to our presence(s) online. You can hear the podcast here, or am embedded player should work below:

Facebook hoping Messenger Kids will draw future users, and their data

Facebook has always had a problem with kids.

Facebook has always had a problem with kids.

The US Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) explicitly forbids the collection of data from children under 13 without parental consent.

Rather than go through the complicated verification processes that involve getting parental consent, Facebook, like most online platforms, has previously stated that children under 13 simply cannot have Facebook accounts.

Of course, that has been one of the biggest white lies of the internet, along with clicking the little button which says you’ve read the Terms of Use; many, many kids have had Facebook accounts — or Instagram accounts (another platform wholly-owned by Facebook) — simply by lying about their birth date, which neither Facebook nor Instagram seek to verify if users indicate they’re 13 or older.

Many children have utilised some or all or Facebook’s features using their parent’s or older sibling’s accounts as well. Facebook’s internal messaging functions, and the standalone Messenger app have, at times, been shared by the named adult account holder and one or more of their children.

Sometimes this will involve parent accounts connecting to each other simply so kids can Video Chat, somewhat messing up Facebook’s precious map of connections.

Enter Messenger Kids, Facebook’s new Messenger app explicitly for the under-13s. Messenger Kids is promoted as having all the fun bits, but in a more careful and controlled space directed by parental consent and safety concerns.

To use Messenger Kids, a parent or caregiver uses their own Facebook account to authorise Messenger Kids for their child. That adult then gets a new control panel in Facebook where they can approve (or not) any and all connections that child has.

Kids can video chat, message, access a pre-filtered set of animated GIFs and images, and interact in other playful ways.

PHOTO: The app has controls built into its functionality that allow parents to approve contacts. (Supplied: Facebook)

PHOTO: The app has controls built into its functionality that allow parents to approve contacts. (Supplied: Facebook)

In the press release introducing Messenger Kids, Facebook emphasises that this product was designed after careful research, with a view to giving parents more control, and giving kids a safe space to interact providing them a space to grow as budding digital creators. Which is likely all true, but only tells part of the story.

As with all of Facebook’s changes and releases, it’s vitally important to ask: what’s in it for Facebook?

While Messenger Kids won’t show ads (to start with), it builds a level of familiarity and trust in Facebook itself. If Messenger Kids allows Facebook to become a space of humour and friendship for years before a “real” Facebook account is allowed, the odds of a child signing up once they’re eligible becomes much greater.

Facebook playing the long game

In an era when teens are showing less and less interest in Facebook’s main platform, Messenger Kids is part of a clear and deliberate strategy to recapture their interest. It won’t happen overnight, but Facebook’s playing the long game here.

If Messenger Kids replaces other video messaging services, then it’s also true that any person kids are talking to will need to have an active Facebook account, whether that’s mum and dad, older cousins or even great grandparents. That’s a clever way to keep a whole range of people actively using Facebook (and actively seeing the ads which make Facebook money).

PHOTO: Mark Zuckerberg and wife Priscilla Chan read ‘Quantum Physics for Babies’ to their son Max. (Facebook: Mark Zuckerberg)

Facebook wants data about you. It wants data about your networks, connections and interactions. It wants data about your kids. And it wants data about their networks, connections and interactions, too.

When they set up Messenger Kids, parents have to provide their child’s real name. While this is consistent with Facebook’s real names policy, the flexibility to use pseudonyms or other identifiers for kids would demonstrate real commitment to carving out Messenger Kids as something and somewhere different. That’s not the path Facebook has taken.

Facebook might not use this data to sell ads to your kids today, but adding kids into the mix will help Facebook refine its maps of what you do (and stop kids using their parents accounts for Video Chat messing up that data). It will also mean Facebook understands much better who has kids, how old they are, who they’re connected to, and so on.

One more rich source of data (kids) adds more depth to the data that makes Facebook tick. And make Facebook profit. Lots of profit.

Facebook’s main app, Messenger, Instagram, and WhatsApp (all owned by Facebook) are all free to use because the data generated by users is enough to make Facebook money. Messenger Kids isn’t philanthropy; it’s the same business model, just on a longer scale.

Facebook isn’t alone in exploring variations of their apps for children.

Google, Amazon and Apple want your kids

As far back as 2013 Snapchat released SnapKidz, which basically had all the creative elements of Snapchat, but not the sharing ones. However, their kids-specific app was quietly shelved the following year, probably for lack of any sort of business model.

PHOTO: The space created by Messenger Kids won’t stop cyberbullying. (ABC News: Will Ockenden )

Since early 2017, Google has also shifted to allowing kids to establish an account managed by their parents. It’s not hard to imagine why, when many children now chat with Google daily using the Google Home speakers (which, really, should be called “listeners” first and foremost).

Google Home, Amazon’s Echo and soon Apple’s soon-to-be-released HomePod all but remove the textual and tactile barriers which once prevented kids interacting directly with these online giants.

A child’s Google Account also allows parents to give them access to YouTube Kids. That said, the content that’s permissible on YouTube Kids has been the subject of a lot of attention recently.

In short, if dark parodies of Peppa Pig where Peppa has her teeth painfully removed to the sounds of screaming is going to upset your kids, it’s not safe to leave them alone to navigate YouTube Kids.

Nor will the space created by Messenger Kids stop cyberbullying; it might not be anonymous, but parents will only know there’s a problem if they consistently talk to their children about their online interactions.

Facebook often proves unable to regulate content effectively, in large part because it relies on algorithms and a relatively small team of people to very rapidly decide what does and doesn’t violate Facebook’s already fuzzy guidelines about acceptability. It’s unclear how Messenger Kids content will be policed, but the standard Facebook approach doesn’t seem sufficient.

At the moment, Messenger Kids is only available in the US; before it inevitably arrives in Australia and elsewhere, parents and caregivers need to decide whether they’re comfortable exchanging some of their children’s data for the functionality that the new app provides.

And, to be fair, Messenger Kids may well be very useful; a comparatively safe space where kids can talk to each other, explore tools of digital creativity, and increase their online literacies, certainly has its place.

Most importantly, though, is this simple reminder: Messenger Kids isn’t (just) screen time, it’s social time. And as with most new social situations, from playgrounds to pools, parent and caregiver supervision helps young people understand, navigate and make the most of those situations. The inverse is true, too: a lack of discussion about new spaces and situations will mean that the chances of kids getting into awkward, difficult, or even dangerous situations goes up exponentially.

Messenger Kids isn’t just making Facebook feel normal, familiar and safe for kids. It’s part of Facebook’s long game in terms of staying relevant, while all of Facebook’s existing issues remain.

Tama Leaver is an Associate Professor in the Department of Internet Studies at Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia.

[This piece was originally published on the ABC News website.]

Reflections and Resources from the 2017 Digitising Early Childhood Conference

Last week’s Digitising Early Childhood conference here in Perth was a fantastic event which brought together so many engaging and provocative scholars in a supportive and policy/action-orientated environment (which I suppose I should call ‘engagement and impact’-orientated in Australia right now). For a pretty well document overview of the conference itself, you can see the quite substantial tweets collected via the #digikids17 hashtag on Twitter, which I’d really encourage you to look over. My head is still buzzing, so instead to trying to synthesise everyone else’s amazing work, I’m just going to quickly point to the material that arose my three different talks in case anyone wishes to delve further.

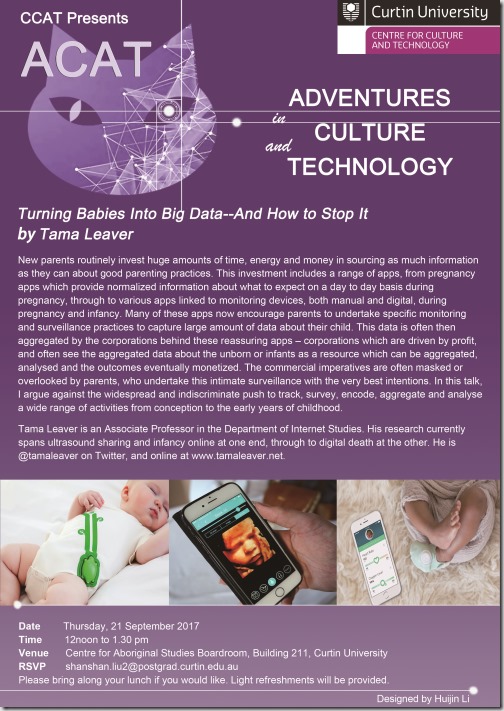

First up, here are the slides for my keynote ‘Turning Babies into Big Data—And How to Stop It’:

[slideshare id=79644515&doc=leaverkeynote-170911155436]

If you’d like to hear the talk that goes with the slides, there’s an audio recording you can download here. (I think these were filmed, so if a link becomes available at some point, I’ll update and post it here.) There was a great response to my talk, which was humbling and gratifying at the same time. There was also quite a lot of press interest, too, so here’s the best pieces that are available online (and may prove a more accessible overview of some of the issues I explored):

If you’d like to hear the talk that goes with the slides, there’s an audio recording you can download here. (I think these were filmed, so if a link becomes available at some point, I’ll update and post it here.) There was a great response to my talk, which was humbling and gratifying at the same time. There was also quite a lot of press interest, too, so here’s the best pieces that are available online (and may prove a more accessible overview of some of the issues I explored):

- Rebecca Turner’s ABC article ‘Owlet Smark Sock prompts warning for parents, fears over babies’ sensitive health data’;

- Leon Compton’s interview on ABC Radio Tasmania ‘Social media and parenting: the do’s and don’ts’ (audio);

- Brigid O’Connell’s Herald Sun story, Parents may be unwittingly turning babies into big data (paywalled); and

- Cathy O’Leary’s story in The Western Australian, Parents airing kids’ lives on social media.

While our argument is still being polished, the slides for this version of Crystal Abidin and my paper From YouTube to TV, and back again: Viral video child stars and media flows in the era of social media are also available:

[slideshare id=79706290&doc=fromyoutubetotvandbackagain-170913025942]

This paper began as a discussion after our piece about Daddy O Five in The Conversation and where the complicated questions about children in media first became prominent. Crystal wasn’t able to be there in person, but did a fantastic Snapchat-recorded 5-minute intro, while I brought home the rest of the argument live. Crystal has a great background page on her website, linking this to her previous work in the area. There was also press interest in this talk, and the best piece to listen to (and hear Crystal and I in dialogue, even though this was recorded at different times, on different continents!):

- Brett Worthington’s Life Matters segment on Radio National, How social media videos turn children into viral sensations (audio)

Finally, as part of the Higher Degree by Research and Early Career Researcher Day which ended the conference, I presented a slightly updated version of my workshop ‘Developing a scholarly web presence & using social media for research networking’:

[slideshare id=79796582&doc=developingascholarlywebpresenceusingsocialmediaforresearchnetworking-170915063232]

Overall, it was a very busy, but very rewarding conference, with new friends made, brilliant new scholarship to digest, and surely some exciting new collaborations begun!

[Photo of the Digitising Early Childhood Conference Keynote Speakers]

Three Upcoming Infancy Online-related events

Over the next month, I’m lucky enough to be involved in three separate events focused on infancy online, digital media and early childhood. The details …

[1] Thinking the Digital: Children, Young People and Digital Practice – Friday, 8th September, Sydney – is co-hosted by the Office of the eSafety Commissioner; Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University; and Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney. The event opens with a keynote by visiting LSE Professor Sonia Livingstone, and is followed by three sessions discussing youth, childhood and the digital age is various forms. While Sonia Livingstone is reason enough to be there, the three sessions are populated by some of the best scholars in Australia, and it should be a really fantastic discussion. I’ll be part of the second session on Rights-based Approaches to Digital Research, Policy and Practice. There are limited places, and a small fee, involved if you’re interested in attending, so registration is a must! To follow along on Twitter, the official hashtag is #ThinkingTheDigital.

The day before this event, Sonia Livingston is also giving a public seminar at WSU’s Parramatta City campus if you’re in able to attend on the afternoon of Thursday, 7th September.

[2] The following week is the big Digitising Early Childhood International Conference 2017 which runs 11-15 September, features a great line-up of keynotes as well as a truly fascinating range of papers on early childhood in the digital age. I’m lucky enough to be giving the conference’s first keynote on Tuesday morning, entitled ‘Turning Babies into Big Data–And How to Stop it’. I’ll also be presenting Crystal Abidin and my paper ‘From YouTube to TV, and Back Again: Viral Video Child Stars and Media Flows in the Era of Social Media‘ on the Wednesday and running a session on the final day called ‘Strategies for Developing a Scholarly Web Presence during a Higher Degree & Early Career’ as part of the Higher Degree by Research/Early Career Researcher Day. It should be a very busy, but also incredibly engaging week! To follow tweets from conference, the official hashtag is #digikids17.

[3] Finally, as part of Research and Innovation Week 2017 at Curtin University, at midday on Thursday 21st September I’ll be presenting a slightly longer version of my talk Turning Babies into Big Data—and How to Stop It in the Adventures in Culture and Technology series hosted by Curtin’s Centre for Culture and Technology. This is a free talk, open to anyone, but please either RSVP to this email, or use the Facebook event page to indicate you’re coming.

When exploiting kids for cash goes wrong on YouTube: the lessons of DaddyOFive

A new piece in The Conversation from Crystal Abidin and me …

Tama Leaver, Curtin University and Crystal Abidin, Curtin University

The US YouTube channel DaddyOFive, which features a husband and wife from Maryland “pranking” their children, has pulled all its videos and issued a public apology amid allegations of child abuse.

The “pranks” would routinely involve the parents fooling their kids into thinking they were in trouble, screaming and swearing at them, only the reveal “it was just a prank” as their children sob on camera.

Despite its removal the content continues to circulate in summary videos from Philip DeFranco and other popular YouTubers who are critiquing the DaddyOFive channel. And you can still find videos of parents pranking their children on other channels around YouTube. But the videos also raise wider issues about children in online media, particularly where the videos make money. With over 760,000 subscribers, it is estimated that DaddyOFive earned between US$200,000-350,000 each year from YouTube advertising revenue.

The rise of influencers

Kid reactions on YouTube are a popular genre, with parents uploading viral videos of their children doing anything from tasting lemons for the first time to engaging in baby speak. Such videos pre-date the internet, with America’s Funniest Home Videos (1989-) and other popular television shows capitalising on “kid moments”.

In the era of mobile devices and networked communication, the ease with which children can be documented and shared online is unprecedented. Every day parents are “sharenting”, archiving and broadcasting images and videos of their children in order to share the experience with friends.

Even with the best intentions, though, one of us (Tama) has argued that photos and videos shared with the best of intentions can inadvertently lead to “intimate surveillance”, where online platforms and corporations use this data to build detailed profiles of children.

YouTube and other social media have seen the rise of influencer commerce, where seemingly ordinary users start featuring products and opinions they’re paid to share. By cultivating personal brands through creating a sense of intimacy with their consumers, these followings can be strong enough for advertisers to invest in their content, usually through advertorials and product placements. While the DaddyOFive channel was clearly for-profit, the distinction between genuine and paid content is often far from clear.

From the womb to celebrity

As with DaddyOFive, these influencers can include entire families, including children whose rights to participate, or choose not to participate, may not always be considered. In some cases, children themselves can be the star, becoming microcelebrities, often produced and promoted by their parents.

South Korean toddler Yebin, for instance, first went viral as a three-year-old in 2014 in a video where her mom was teaching her to avoid strangers. Since then, Yebin and her younger brother have been signed to influencer agencies to manage their content, based on the reach of their channel which has accumulated over 21 million views.

As viral videos become marketable and kid reaction videos become more lucrative, this may well drive more and more elaborate situations and set-ups. Yet, despite their prominence on social media, such children in internet-famous families are not clearly covered by the traditional workplace standards (such as Child Labour Laws and that Coogan Law in the US), which historically protected child stars in mainstream media industries from exploitation.

This is concerning especially since not only are adult influencers featuring their children in advertorials and commercial content, but some are even grooming a new generation of “micro-microcelebrities” whose celebrity and careers begin in the womb.

In the absence of any formal guidelines for the child stars of social media, it is the peers and corporate platforms that are policing the welfare of young children. As prominent YouTube influencers have rallied to denounce the parents behind the DaddyOFive accusing them of child abuse, they have also leveraged their influence to report the parents of DaddyOFive to child protective services. YouTube has also reportedly responded initially by pulling advertising from the channel. YouTubers collectively demonstrating a shared moral position is undoubtedly helpful.

Greater transparency

The question of children, commerce and labour on social media is far from limited to YouTube. Australian PR director Roxy Jacenko has, for example, defended herself against accusations of exploitation after launching and managing a commercial Instagram account for her her young daughter Pixie, who at three-years-old was dubbed the “Princess of Instagram”. And while Jacenko’s choices for Pixie may differ from many other parents, at least as someone in PR she is in a position to make informed and articulated choices about her daughter’s presence on social media.

Already some influencers are assuring audiences that child participation is voluntary, enjoyable, and optional by broadcasting behind-the-scenes footage.

Television, too, is making the most of children on social media. The Ellen DeGeneres Show, for example, regularly mines YouTube for viral videos starring children in order to invite them as guests on the show. Often they are invited to replicate their viral act for a live audience, and the show disseminates these program clips on its corporate YouTube channel, sometimes contracting viral YouTube children with high attention value to star in their own recurring segments on the show.

Ultimately, though, children appearing on television are subject to laws and regulations that attempt to protect their well-being. On for-profit channels on YouTube and other social media platforms there is a little transparency about the role children are playing, the conditions of their labour, and how (and if) they are being compensated financially.

Children may be a one-off in parents’ videos, or the star of the show, but across this spectrum, social media like YouTube need rules to ensure that children’s participation is transparent and their well-being paramount.

Tama Leaver, Associate Professor in Internet Studies, Curtin University and Crystal Abidin, Adjunct Research Fellow at the Centre for Culture and Technology (CCAT), Curtin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.