Home » Infancy Online

Category Archives: Infancy Online

Spotlight forum: social media, child influencers and keeping your kids safe online

I was pleased to join Associate Professor Crystal Abidin as panellists on the ABC Perth Radio Spotlight Forum on social media, child influencers and keeping your kids safe online. It was a wide-ranging discussion that really highlights community interest and concern in ensuring our young people have the best access to opportunities online while minimising the risks involved.

You can listen to a recording of the broadcast here.

Instagram’s privacy updates for kids are positive. But plans for an under-13s app means profits still take precedence

Shutterstock

By Tama Leaver, Curtin University

Facebook recently announced significant changes to Instagram for users aged under 16. New accounts will be private by default, and advertisers will be limited in how they can reach young people.

The new changes are long overdue and welcome. But Facebook’s commitment to childrens’ safety is still in question as it continues to develop a separate version of Instagram for kids aged under 13.

The company received significant backlash after the initial announcement in May. In fact, more than 40 US Attorneys General who usually support big tech banded together to ask Facebook to stop building the under-13s version of Instagram, citing privacy and health concerns.

Privacy and advertising

Online default settings matter. They set expectations for how we should behave online, and many of us will never shift away from this by changing our default settings.

Adult accounts on Instagram are public by default. Facebook’s shift to making under-16 accounts private by default means these users will need to actively change their settings if they want a public profile. Existing under-16 users with public accounts will also get a prompt asking if they want to make their account private.

These changes normalise privacy and will encourage young users to focus their interactions more on their circles of friends and followers they approve. Such a change could go a long way in helping young people navigate online privacy.

Facebook has also limited the ways in which advertisers can target Instagram users under age 18 (or older in some countries). Instead of targeting specific users based on their interests gleaned via data collection, advertisers can now only broadly reach young people by focusing ads in terms of age, gender and location.

This change follows recently publicised research that showed Facebook was allowing advertisers to target young users with risky interests — such as smoking, vaping, alcohol, gambling and extreme weight loss — with age-inappropriate ads.

This is particularly worrying, given Facebook’s admission there is “no foolproof way to stop people from misrepresenting their age” when joining Instagram or Facebook. The apps ask for date of birth during sign-up, but have no way of verifying responses. Any child who knows basic arithmetic can work out how to bypass this gateway.

Of course, Facebook’s new changes do not stop Facebook itself from collecting young users’ data. And when an Instagram user becomes a legal adult, all of their data collected up to that point will then likely inform an incredibly detailed profile which will be available to facilitate Facebook’s main business model: extremely targeted advertising.

Deploying Instagram’s top dad

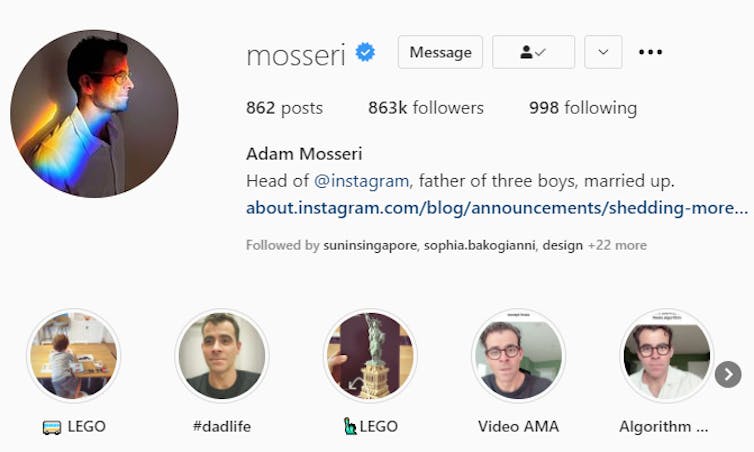

Facebook has been highly strategic in how it released news of its recent changes for young Instagram users. In contrast with Facebook’s chief executive Mark Zuckerberg, Instagram’s head Adam Mosseri has turned his status as a parent into a significant element of his public persona.

Since Mosseri took over after Instagram’s creators left Facebook in 2018, his profile has consistently emphasised he has three young sons, his curated Instagram stories include #dadlife and Lego, and he often signs off Q&A sessions on Instagram by mentioning he needs to spend time with his kids.

When Mosseri posted about the changes for under-16 Instagram users, he carefully framed the news as coming from a parent first, and the head of one of the world’s largest social platforms second. Similar to many influencers, Mosseri knows how to position himself as relatable and authentic.

Age verification and ‘potentially suspicious’ adults

In a paired announcement on July 27, Facebook’s vice-president of youth products Pavni Diwanji announced Facebook and Instagram would be doing more to ensure under-13s could not access the services.

Diwanji said Facebook was using artificial intelligence algorithms to stop “adults that have shown potentially suspicious behavior” from being able to view posts from young people’s accounts, or the accounts themselves. But Facebook has not offered an explanation as to how a user might be found to be “suspicious”.

Diwanji notes the company is “building similar technology to find and remove accounts belonging to people under the age of 13”. But this technology isn’t being used yet.

It’s reasonable to infer Facebook probably won’t actively remove under-13s from either Instagram or Facebook until the new Instagram For Kids app is launched — ensuring those young customers aren’t lost to Facebook altogether.

Despite public backlash, Diwanji’s post confirmed Facebook is indeed still building “a new Instagram experience for tweens”. As I’ve argued in the past, an Instagram for Kids — much like Facebook’s Messenger for Kids before it — would be less about providing a gated playground for children and more about getting children familiar and comfortable with Facebook’s family of apps, in the hope they’ll stay on them for life.

A Facebook spokesperson told The Conversation that a feature introduced in March prevents users registered as adults from sending direct messages to users registered as teens who are not following them.

“This feature relies on our work to predict peoples’ ages using machine learning technology, and the age people give us when they sign up,” the spokesperson said.

They said “suspicious accounts will no longer see young people in ‘Accounts Suggested for You’, and if they do find their profiles by searching for them directly, they won’t be able to follow them”.

Resources for parents and teens

For parents and teen Instagram users, the recent changes to the platform are a useful prompt to begin or to revisit conversations about privacy and safety on social media.

Instagram does provide some useful resources for parents to help guide these conversations, including a bespoke Australian version of their Parent’s Guide to Instagram created in partnership with ReachOut. There are many other online resources, too, such as CommonSense Media’s Parents’ Ultimate Guide to Instagram.

Regarding Instagram for Kids, a Facebook spokesperson told The Conversation the company hoped to “create something that’s really fun and educational, with family friendly safety features”.

But the fact that this app is still planned means Facebook can’t accept the most straightforward way of keeping young children safe: keeping them off Facebook and Instagram altogether.

![]()

Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Future Of Children’s Online Privacy

I was delighted to join Dr Anna Bunn, Deputy Head of Curtin Law School, and the Future Of team for a podcast interview all about Children’s Online Privacy.

The half hour podcast is online here in various formats, including shownotes, or embedded in this post:

We discuss:

What’s the impact of parents sharing content of their children online? And what rights do children have in this space?

In this episode, Jessica is joined by Dr Anna Bunn, Deputy Head of Curtin Law School and Tama Leaver, Professor of Internet Studies at Curtin University to discuss “sharenting” – the growing practice of parents sharing images and data of their children online. The three examine the social, legal and developmental impacts a life-long digital footprint can have on a child.

- What is the impact of sharing child-related content on our kids? [04:08]

- What type of tools and legal protections would you like to see in the future to protect children? [16:30]

- At what age can a child give consent to share content [18:25]

- What about the right to be forgotten [21:11]

- What’s best practice for sharing child-related content online? [26:01]

Life and Death on Social Media Podcast

As part of Curtin University’s new The Future Of podcast series, I was recently interviewed about my ongoing research into pre-birth and infancy at one end, and digital death at the other, in relation to our presence(s) online. You can hear the podcast here, or am embedded player should work below:

Reflections and Resources from the 2017 Digitising Early Childhood Conference

Last week’s Digitising Early Childhood conference here in Perth was a fantastic event which brought together so many engaging and provocative scholars in a supportive and policy/action-orientated environment (which I suppose I should call ‘engagement and impact’-orientated in Australia right now). For a pretty well document overview of the conference itself, you can see the quite substantial tweets collected via the #digikids17 hashtag on Twitter, which I’d really encourage you to look over. My head is still buzzing, so instead to trying to synthesise everyone else’s amazing work, I’m just going to quickly point to the material that arose my three different talks in case anyone wishes to delve further.

First up, here are the slides for my keynote ‘Turning Babies into Big Data—And How to Stop It’:

If you’d like to hear the talk that goes with the slides, there’s an audio recording you can download here. (I think these were filmed, so if a link becomes available at some point, I’ll update and post it here.) There was a great response to my talk, which was humbling and gratifying at the same time. There was also quite a lot of press interest, too, so here’s the best pieces that are available online (and may prove a more accessible overview of some of the issues I explored):

If you’d like to hear the talk that goes with the slides, there’s an audio recording you can download here. (I think these were filmed, so if a link becomes available at some point, I’ll update and post it here.) There was a great response to my talk, which was humbling and gratifying at the same time. There was also quite a lot of press interest, too, so here’s the best pieces that are available online (and may prove a more accessible overview of some of the issues I explored):

- Rebecca Turner’s ABC article ‘Owlet Smark Sock prompts warning for parents, fears over babies’ sensitive health data’;

- Leon Compton’s interview on ABC Radio Tasmania ‘Social media and parenting: the do’s and don’ts’ (audio);

- Brigid O’Connell’s Herald Sun story, Parents may be unwittingly turning babies into big data (paywalled); and

- Cathy O’Leary’s story in The Western Australian, Parents airing kids’ lives on social media.

While our argument is still being polished, the slides for this version of Crystal Abidin and my paper From YouTube to TV, and back again: Viral video child stars and media flows in the era of social media are also available:

This paper began as a discussion after our piece about Daddy O Five in The Conversation and where the complicated questions about children in media first became prominent. Crystal wasn’t able to be there in person, but did a fantastic Snapchat-recorded 5-minute intro, while I brought home the rest of the argument live. Crystal has a great background page on her website, linking this to her previous work in the area. There was also press interest in this talk, and the best piece to listen to (and hear Crystal and I in dialogue, even though this was recorded at different times, on different continents!):

- Brett Worthington’s Life Matters segment on Radio National, How social media videos turn children into viral sensations (audio)

Finally, as part of the Higher Degree by Research and Early Career Researcher Day which ended the conference, I presented a slightly updated version of my workshop ‘Developing a scholarly web presence & using social media for research networking’:

Overall, it was a very busy, but very rewarding conference, with new friends made, brilliant new scholarship to digest, and surely some exciting new collaborations begun!

[Photo of the Digitising Early Childhood Conference Keynote Speakers]

Intimate Surveillance: Normalizing Parental Monitoring and Mediation of Infants Online

At yesterday’s outstanding Controlling Data: Somebody Think of the Children symposium I presented the first version of my new paper “Intimate Surveillance: Normalizing Parental Monitoring and Mediation of Infants Online.” Here’s the abstract:

Parents are increasingly sharing information about infants online in various forms and capacities. In order to more meaningfully understand the way parents decide what to share about young people, and the way those decisions are being shaped, this paper focuses on two overlapping areas: parental monitoring of babies and infants through the example of wearable technologies; and parental mediation through the example of the public sharing practices of celebrity and influencer parents. The paper begins by contextualizing these parental practices within the literature on surveillance, with particular attention to online surveillance and the increasing importance of affect. It then gives a brief overview of work on pregnancy mediation, monitoring on social media, and via pregnancy apps, which is the obvious precursor to examining parental sharing and monitoring practices regarding babies and infants. The examples of parental monitoring and parental mediation will then build on the idea of “intimate surveillance” which entails close and seemingly invasive monitoring by parents. Parental monitoring and mediation contribute to the normalization of intimate surveillance to the extent that surveillance is (re)situated as a necessary culture of care. The choice to not survey infants is thus positioned, worryingly, as a failure of parenting.

An mp3 recording of the audio is available, and the slides are below:

The full version of this paper is currently under review, but if you’re interested in reading the draft, just email me.